Demonstrations over the proposed “Software Patent Directive” in Europe (since rejected by the EU Parliament) were sometimes quite theatrical, and involved at least one “naval battle”. Mikko Rauhala created an ingenious way to counteract the influence of large corporations who were promoting the idea that software patents should be allowed in Europe—he collected pledges of money from the public to offer as bribes to politicians. A “Software Patent Violation Contest” was also organised.

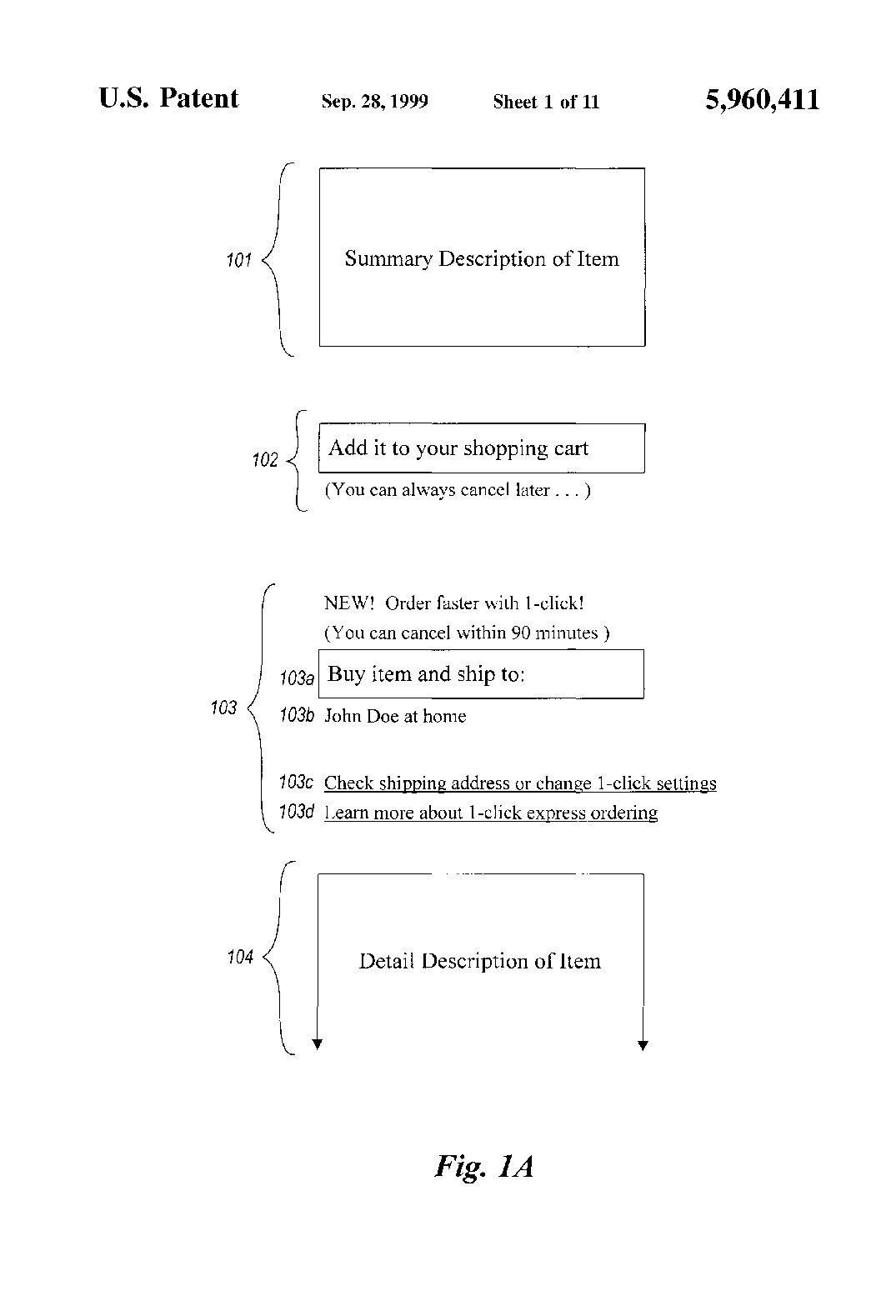

Richard Stallman and Tim O’Reilly both organised protest actions against Amazon.com’s “One-Click” patent in the USA, which claims a monopoly over the idea of ordering an item with a “single action” such as the click of a mouse button.

Non-profit groups such as the EFF and PUBPAT in the USA, and the FFII in Europe, have made it their mission to attack and destroy software patents.

A blogger has succeeded in forcing a re-examination of the infamous Amazon “one-click patent” by presenting new prior art to the United States Patent Office.

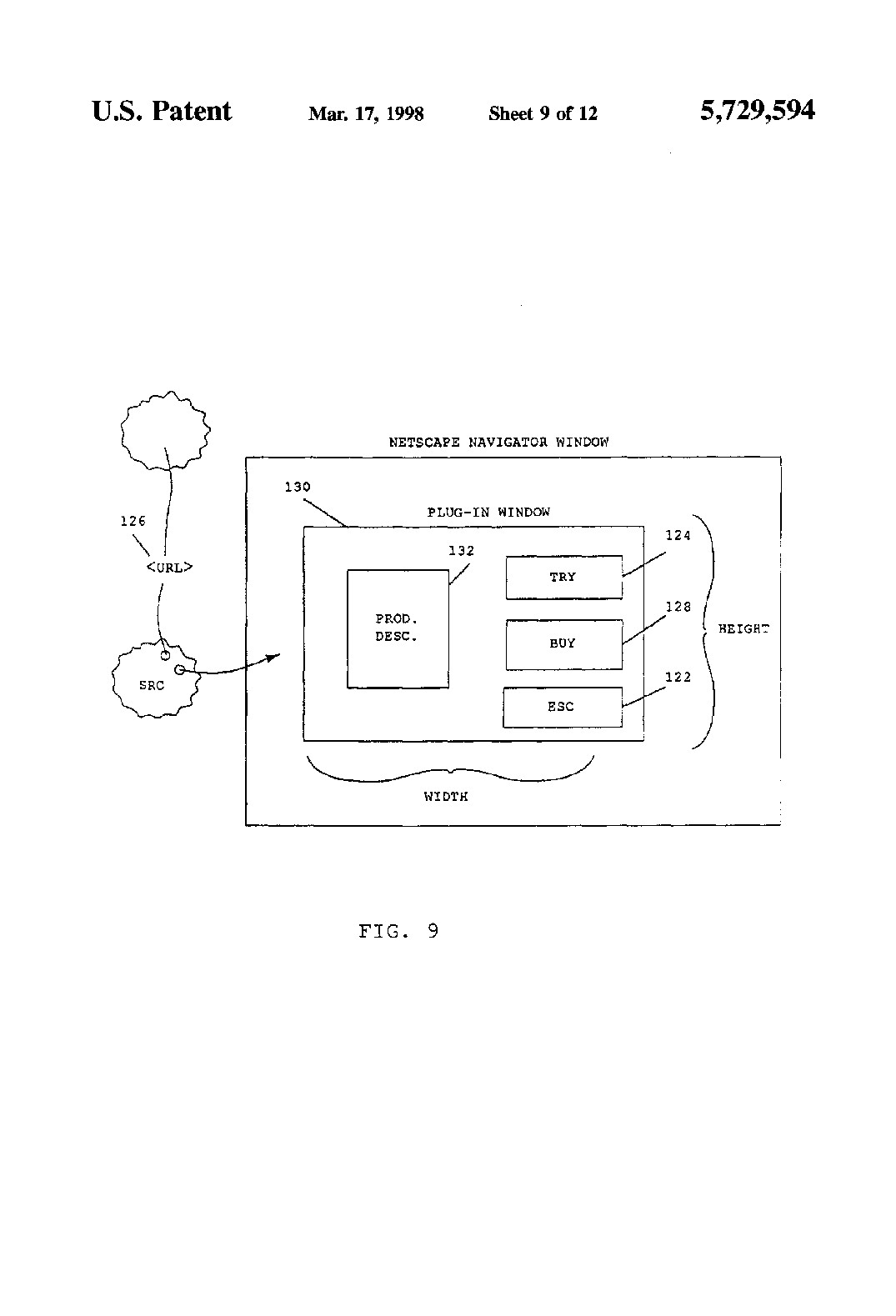

Comparison between figure 9 of the prior art patent and figure 1A of the “One-click” patent

However, the holders of software patents aren’t exactly inactive either. Powerful lobby groups promote the idea that software should be patentable—and at the end of the day, patent holders will enforce their monopolies. The current suit by Firestar against Red Hat could be a portent of things to come.

So what exactly are these software patents that get people so excited? In this article I’ll take a look at US software and business method patents.

Background

Patents on information processing have been around for a long time. 19th century punch-card machine patents abound, and remarkably “software-like” encryption methods were patented during the First World War. What has really changed over the years is how they have fared in court.

In the 1853 case, O’Reilly v. Morse, claims such as:

“...the use of the motive power of the electric or galvanic current, which I call electro-magnetism, however developed, for making or printing intelligible character, letters or signs, at any distances...”

were struck down.

Software patents were foreshadowed by cases like Cochane v. Deemer (1877) (concerned an invention relating to flour making), in which the Supreme Court held that

“A process may be patentable, irrespective of the particular form of the instrumentality used.”

In MacKay Radio & Telegraph Co. v. Radio Corp. of America, a 1939 case about a radio antenna designed to a mathematical formula, it was held that:

“While a scientific truth, or the mathematical expression of it, is not patentable invention, a novel and useful structure created with the aid of knowledge of a scientific truth may be.”

Nevertheless, for a long time software was considered to be within the realm of such things as “abstract ideas”, “scientific truths” or “mathematical expressions” all of which were banned by statute from being patented. This meant that many key software innovations (such as the basic idea for the spreadsheet) were never patented.

For example, in Gottschalk v. Benson (1972), in which the claims were for converting binary-coded decimal numbers into binary numbers, it was stated:

“It is conceded that one may not patent an idea. But in practical effect that would be the result if the formula for converting BCD numerals to pure binary numerals were patented in this case. The mathematical formula involved here has no substantial practical application except in connection with a digital computer, which means that if the judgement below is affirmed, the patent would wholly pre-empt the mathematical formula and in practical effect would be a patent on the algorithm itself.”

and

“Phenomena of nature, though just discovered, mental processes, and abstract intellectual concepts are not patentable, as they are the basic tools of scientific and technological work.”

In Parker v. Flook (1978) the claims were for updating a number called the alarm limit used to control a chemical process. It was stated:

“...respondent’s process is unpatentable under § 101, not because it contains a mathematical algorithm as one component, but because once that algorithm is assumed to be within the prior art, the application, considered as a whole, contains no patentable invention.”

and

“Very simply, our holding today is that a claim for an improved method of calculation even when tied to a specific end use, is unpatentable subject matter under § 101...”

“§ 101” here refers to 35 U.S.C § 101, which provides the statutory basis for patentable subject matter:

“Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.”

Rise of the software patents

A number of cases gradually changed the anti-software patent stance, beginning in 1981 with Diamond v. Diehr (a computer-controlled process for curing rubber). Other examples were In re Alappat (creating a smooth waveform display in a digital oscilloscope), the pivotal State Street Bank (a “hub-and-spoke mutual fund management system”), and AT&T v. Excel (adding a data field to a standard message record in a telecommunications system).

Alapatt addressed the Board of Appeal’s concern that the claims read on a general purpose computer:

“We have held that such programming creates a new machine, because a general purpose computer in effect becomes a special purpose computer once it is programmed to perform particular functions pursuant to instructions from program software.”

State Street Bank held:

“Today we hold that the transformation of data, representing discrete dollar amounts, by a machine through a series of mathematical calculations into a final share price, constitutes a practical application of a mathematical algorithm, formula or calculation, because it produces “a useful, concrete and tangible result”—a final share price momentarily fixed for recording and reporting purposes and even accepted and relied upon by regulatory authorities in subsequent trades.”

One issue that reared its head during these early pro-software-patent decisions was whether what the inventor had claimed to have discovered was in fact statutory subject matter. If the alleged inventive idea was in fact non-statutory subject matter, but the claim was drafted to recite some statutory structure, should the claim be granted? The courts seemed to think so.

However, looking at some of the dissenting opinions, these decisions weren’t made without a fight. For example in Diamond v. Diehr, Justice Stevens for the minority stated:

“The Court...fails to understand or completely disregards the distinction between the subject matter of what the inventor claims to have discovered—the § 101 issue—and the question whether that claimed discovery is in fact novel—the § 102 issue.”

The dissent in Alapatt was even more interesting:

This said that the majority took the simplistic approach of looking at whether the claim reads on structure and ignored the “claimed invention or discovery for which a patent is sought”.

Judge Archer stated:

“The dispositive issue is whether the invention or discovery for which an award of patent is sought is more than just a discovery in abstract mathematics.”

Nevertheless, the idea took hold that if your “invention” was entirely in the field of non-statutory subject matter, but your claim recited some allowed structure, you could get a patent.

As an extension of the idea of software patents, patents on pure business methods also began to appear.

Although 19th century patents can be found relating to information processing methods for business purposes, an important example in the modern era was the Merrill Lynch patent (4,376,978) on a cash management account.

A 2005 decision, Ex parte Lundgren, concerned a patent on a “method of compensating a manager” that involved calculating compensation based on performance criteria and then transferring payment to the manager. This decision seems to allow business method patents to exist without using “technological arts”.

The USPTO has since set in place interim examination guidelines stating that “if the claimed invention physically transforms an article or physical object to a different state or thing, or if the claimed invention otherwise produces a useful, concrete, and tangible result” then it will fall within § 101.

Back in the real world

Cases like Computer Associates v. Altai and Lotus v. Borland showed the limited ability of copyright to protect software, which encouraged developers to seek patent protection.

The growth of the internet led to more software patents than most people could keep track of, making it almost impossible to know if a new project would infringe some patent or other. Many developers became alarmed not only by the sheer number of software patents, but that they seemed to claim simple combinations of previously well-known ideas as inventions, with very little “inventiveness” involved.

A patent application is examined by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to see if it is not only novel (i.e. new) but also “nonobvious”. Nonobviousness is summarised on the USPTO website as:

“The subject matter sought to be patented must be sufficiently different from what has been used or described before that it may be said to be nonobvious to a person having ordinary skill in the area of technology related to the invention. For example, the substitution of one color for another, or changes in size, are ordinarily not patentable.”

However, a number of these new software patents seemed to the average person to claim matter that was neither novel nor nonobvious. Partly this was because people did not comprehend how low the standards of nonobviousness really were. As stated by Stephen C. Glazier in his book “Patent Strategies for business”:

“To most technical people, this obviousness hurdle seems to mean that, in retrospect, an invention must involve a new scientific discovery, or a new engineering principle. This, however, is not the legal view of obviousness.”

That such a low level of innovation was required to obtain a patent was largely due to decisions of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). The CAFC developed a requirement for a “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” to combine previously existing references in order to show that an invention was obvious. This made it harder to show obviousness, even if prior art could be found.

However, it also became apparent that the USPTO had difficulty finding software-related “prior art”, such as documents showing what had been used or described before the date of invention, to consult when examining the patent applications. Many well-known programming techniques were either simply part of “general knowledge” or recorded in places not normally accessible to patent examiners.

Software patents came to be viewed as a weapon used by large firms to attack smaller firms who could not afford to develop and enforce their own patent portfolios. Sometimes it worked the other way: Stac Electronics sued Microsoft for patent infringement, receiving a judgement of about $120 million, and a permanent injunction against Microsoft.

Where are we going today?

During the brief history of software patents, debate has been focused on whether software is patentable in principle—and as shown above, it has generally come out in the affirmative. So, anyone trying to have software or business patents thrown out on principle today will have an uphill battle—particularly in the face of the huge vested interests that have developed.

Lack of novelty and obviousness are two important remaining weapons for attacking software patents. However, the way the USPTO and the CAFC have interpreted the legal “obviousness” test is a problem. It has developed into something completely different from the common-sense notion of what is “obvious”—and it’s not just where software is concerned.

Patents have been issued on things such as tennis strokes, training a janitor, or exercising a cat using a laser pointer. Recent patent applications that have made headlines have included those for storylines, or for a method of swinging on a swing.

It seems that not only is the definition of what is patentable expanding without bound, (see Ex parte Lundgren above) but the level of inventiveness that needs to be shown is diminishing to zero.

But might the playing field be levelled a little in the future?

If you can’t beat’em

KSR v. Teleflex will soon be addressed by the Supreme Court. This case has the potential to give obviousness a lot more “teeth”. It relates to accelerator pedals for cars rather than software, but could have important ramifications for patents in general.

It has raised the spectre of Supreme Court cases such as Sakraida v. Ag Pro, Inc which stated (quoting Great A. & P. Tea Co. v. Supermarket Corp):

“...A patent for a combination which only unites old elements with no change in their respective functions...obviously withdraws what already is known into the field of its monopoly and diminishes the resources available to skillful men...”

If the elements of a combination claim have to have a change in their respective functions to be held nonobvious, would this affect the current crop of software patents that seem to simply cobble together elements that were already known?

After all, Sakraida was about a water flush system to remove cow manure from the floor of a dairy barn.