The person who invented the concept of shared libraries should be given a raise... and a bonus. The person who decided that shared library management and naming conventions should be left to the implementation should be flogged.

This opinion is the result of too much negative experience on my part with building shared libraries for multiple platforms without the aid of Libtool. The very existence of Libtool stands as a witness to the truth of this sentiment.

Libtool exists for one purpose only--to provide a standardized, abstract interface for developers desiring to create portable shared libraries. It abstracts both the shared library build process, and the programming interfaces used to dynamically load and access shared libraries at run time.

This chapter has downloads!

Before I get into a discussion of the proper use of Libtool, I should probably spend a few minutes on the features and functionality provided by shared libraries, so that you will understand the scope of the material I'm covering here.

The benefits of shared libraries

Shared libraries provide a way to ship reusable chunks of functionality in a convenient package that can be loaded into a process address space, either automatically at program load time by the operating system loader, or by code in the application itself, when it decides to load and access the library's functionality. The point at which an application binds functionality from a shared library is very flexible, and determined by the developer, based on the design of the program and the needs of the end-user.

The interfaces between the program executable and modules defined as shared libraries must be well-designed by virtue of the fact that shared library interfaces must be well-specified. This rigorous specification promotes good design practices. When you use shared libraries, you're essentially forced to be a better programmer.

Shared libraries may be (as the name implies) shared among processes. This sharing is very literal. The code segments for a shared library can be loaded once into physical memory pages. Those same memory pages can then be mapped into the process address spaces for multiple programs. The data pages must, of course, be unique per process, but global data segments are often small compared to the code segments of a shared library. This is true efficiency.

Shared libraries are easily updated during program upgrades. The base program may not have changed at all between two revisions of a software package. A new version of a shared library may be laid down on top of the old version, as long as its interfaces have not been changed. When interfaces are changed, two versions of the same shared library may co-exist side-by-side, because the versioning scheme used by shared libraries (and supported by Libtool) allows the library files to be named differently, but treated as the same library. Older programs may continue to use older versions of the library, while newer programs may use the newer versions.

If a software package specifies a well-defined "plug-in" interface, then shared libraries can be used to implement user-configurable loadable functionality. This means that additional functionality can become available to a program after it's been released, and third-parties can even add functionality to your program, if you publish a document describing your plug-in interface specification.

There are a few widely-known examples of systems such as this. Eclipse, for instance, is almost a pure plug-in framework. The base executable supports little more than a well-defined plug-in interface. Most of the functionality in an Eclipse application comes from library functions. Granted, Eclipse is written in Java, and uses Java class libraries, but the same concept can be (and has been) easily implemented in C or C++ using shared libraries.

How shared libraries work

As I mentioned above, the way a POSIX-based operating system implements shared libraries varies from platform to platform, but the general idea is the same for all platforms. The following discussion applies to shared library references that are resolved by the linker while the program is being built, and by the operating system loader at program load time.

Dynamic linking at load time

As a program executable image is being built, the linker (formally called a "link editor") maintains a table of unresolved function entry points and global data references. Each new symbol referenced by the object code being linked together, is added to this table. At the end of the linking process, all object files containing only unreferenced symbols are removed from the link list. All object files containing referenced symbols are linked together, and become part of the program executable image. If there are any outstanding references in the symbol table after all of the object files have been analyzed in this manner, the linker exits with an error message. On success, the final executable image may then be loaded and executed by a user. It is entirely self-contained, depending only upon itself.

Assuming that all undefined references are resolved during the linking process, if the list of objects to be linked contains one or more shared libraries, the linker will build the executable image from all non-shared objects specified on the linker command line. This includes all individual .o files and all static library archives. However it will add two tables to the binary image header; the first is the table of outstanding external references--those found only in shared libraries, and the second is a table of shared library names and versions in which the outstanding undefined references were found.

Later, when the operating system loader attempts to load this program, it must resolve the remaining outstanding references to symbols imported from the shared libraries named in the executable header. If the loader can't resolve all of the references, then a load error occurs, and the process is terminated with an operating system error message.

Note here that these external symbols are not tied to a specific shared library. The operating system will stop loading shared libraries as soon as it is able to resolve all of the outstanding symbol references. Usually, this happens after the last indicated shared library is loaded into the process address space, but there are exceptions.

NOTE: This process differs a bit from the way a Windows operating system resolves symbols in Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs). On Windows, a particular symbol is tied by the linker at program build time to a specifically named DLL.

Using free-floating external references has both pros and cons. On some operating systems, unbound symbols can be satisfied by a library specified by the user. That is, a user can entirely replace a library (or a portion of a library) at run time by simply preloading one that contains the same symbols. On BSD and Linux based systems, for example, a user can use the "LD_PRELOAD" environment variable to inject a shared library into a process address space. Since such libraries are loaded first by the loader before any other libraries, symbols in the preloaded libraries will be located first by the loader when it tries to resolve external references.

In the following example, the "df" utility is executed in an environment containing the LD_PRELOAD variable, set to a path referring to a library that presumably contains a heap manager. This technique can be used to debug problems in your programs. By preloading your own heap manager, you can capture memory leaks in a log file, or debug memory block overruns. This sort of technique is used by such widely-known debugging aids as the valgrind package.

$ LD_PRELOAD=~/lib/libmymalloc.so /bin/df

...

Unfortunately, free-floating symbols can also lead to problems. For instance, two libraries can provide the same symbol name, and the dynamic loader can inadvertently bind an executable to a symbol from the wrong library. At best, this will cause a program crash when the wrong arguments are passed to the mis-matched function. At worst, it can present security risks, because the mis-matched function might be used to capture passwords and security credentials passed by the unsuspecting program.

C-language symbols do not include parameter information, so it's rather likely that symbols will clash in this manner. C++ symbols are a bit safer, in that the entire function signature (minus the return type) is encoded into the symbol name. However, even C++ is not immune to hackers purposely replacing security functions with their own versions of those functions.

Automatic dynamic linking at run time

The operating system loader can also use a very late form of binding, often referred to as "lazy binding". In this situation, the external reference entries in the jump table in the program header are initialized such that they refer to code in the dynamic loader itself.

When a program first calls such a "lazy" entry, the call will be routed to the loader, which will then (potentially) load the proper shared library, determine the actual address of the function, reset the entry point in the jump table, and finally redirect to the (now available) shared library function. The next time this happens, the jump table entry will have been correctly initialized, and the program will jump directly to the called function.

This lazy binding mechanism makes for very fast program startup, because shared libraries whose symbols are not bound until they're needed aren't even loaded until they're first referenced by the application program. Now, consider this--they may never be referenced. Which means they may never be loaded, saving both time and space. An example of this situation might be a word processor with a thesaurus feature, implemented in a shared library. How often do you use your thesaurus? Using automatic dynamic linking, chances are that the shared library containing the thesaurus code will never be loaded in a given execution of your word processor.

The problems with this method should be obvious, at this point. While using automatic run-time dynamic linking can give you faster load times, and better performance and space efficiency, it can also cause abrupt terminations of your application--without warning. If the loader can't find the requested symbol--perhaps the required library is missing--then it has no recourse except to abort the process.

Why not ensure that all symbols exist when the program is loaded? Well, if the loader resolved all symbols at load time, then it might as well populate the jump table entries at that point. After all, it had to load all the libraries to ensure that the symbols actually exist. This then entirely defeats the purpose of this binding method. Furthermore, even if the loader did bother to check out all external references at the point when the program was first started, there's nothing to stop someone from deleting one or more of these libraries before it's used, while the program is still running. Thus, even the pre-check is defeated.

The moral of this story is that you get what you pay for. If you don't want to pay the insurance premium for longer up-front load times, and more space consumed (even if you may never really need it), then you may have to take the hit of a missing symbol at run time, causing a program crash.

Manual dynamic linking at run time

One possible solution to the aforementioned problem is to take personal responsibility for the work done by the system loader. Then, when things don't go right, you have a little more control over the outcome. In the case of the thesaurus module, was it really necessary to terminate the program if the thesaurus library could not be loaded or didn't provide the correct symbols? Of course not, but the loader didn't know that. Only the programmer can make such value judgements.

When a program manages dynamic linking manually at run-time, the linker is left entirely out of the equation. The program doesn't call any shared library functions directly. Rather, shared library functions are referenced though function pointers that are populated by the application program itself at run time.

The way this works is that a program calls an operating system function to manually load a shared library into its own process address space. This system function returns a "handle", or an opaque value representing the loaded library. The program then calls another loader function to import a symbol from the library referred to by the handle. If all goes well, the operating system returns the address of the requested function or data item in the desired library. The program may then call the function, or access the global data item through this pointer.

If something goes wrong in one of these two steps--say the library could not be found, or the symbol was not found within the library, then it becomes the responsibility of the program to define the results--perhaps display an error message, indicating that the program was not configured correctly.

This is a little nicer than the way automatic dynamic run-time linking works; while the loader has no option but to abort, the application has a higher-level perspective, and can handle the problem much more gracefully. The drawback, of course, is that you as the programmer have to manage the process of loading libraries and importing symbols within your application code. However, this process is not really very difficult, as I'll explain later in this chapter.

Using Libtool

An entire book could be written about the details of shared libraries and their implementations on various systems. This short primer will suffice for your immediate needs; so I'll move on to how Libtool can be used to make a package maintainer's life a little easier.

The Libtool project was started in 1996 by Gordon Matzigkeit. Libtool was designed to extend Automake, but can be used independently within hand-coded makefiles, as well. The Libtool project is currently maintained by Bob Friesenhahn, Peter O'Gorman, Gary Vaughan and Ralf Wildenhues.

Abstracting the build process

First, I'll look at how Libtool helps during the build process. Libtool provides a script (ltmain.sh) that config.status executes in a Libtool-enabled project. The ltmain.sh script builds a custom version of the libtool script, specifically for your package. This libtool script is then used by your project's makefiles to build shared libraries specified using the LTLIBRARIES primary. The libtool script is really just a fancy wrapper around the compiler, linker and other tools. The ltmain.sh script should be shipped in a distribution tarball, as part of your end-user build system. Automake-generated rules ensure that this happens properly.

The libtool script insulates the build system author from the nuances of building shared libraries on multiple platforms. This script accepts a well-defined set of options, converting them to appropriate platform- and linker-specific options on the target platform and tool set. Thus, the maintainer need not worry about the specifics of building shared libraries on each platform. She need only understand the available libtool script options. These are well specified in the GNU Libtool manual, and I'll cover many of them in this chapter.

On systems that don't support shared libraries at all, the libtool script uses appropriate commands and options to build and link static libraries. This is all done in such a way that the maintainer is isolated from the differences between building shared libraries and static libraries.

You can emulate building your package on a static-only system by using the "--disable-shared" option on the configure command line for your project. This causes Libtool to assume that shared libraries cannot be built on the target system.

Abstraction at run-time

Libtool can also be used to abstract the programming interfaces supplied by the operating system for loading libraries and importing symbols. Programmers who've ever dynamically loaded a library on a Linux system are familiar with the standard Linux shared library API, including the functions, dlopen, dlsym and dlclose. These functions are provided by a system-level shared library, usually named "dl". Unfortunately, not all POSIX systems that support shared libraries provide the dl library, or functions using these names.

To address these differences, Libtool provides a shared library called "ltdl", which provides a clean, portable library management interface, very similar to the dlopen interface provided by the Linux loader. The use of this library is optional, of course, but highly recommended, because it provides more than just a common API across shared library platforms. It also provides an abstraction for manual run-time dynamic linking between shared library and non-shared library platforms.

"What!? How can that work?" You might ask. On systems that don't provide shared libraries, Libtool actually creates internal symbol tables within the executable containing all of the symbols that would otherwise be found in shared libraries on systems that support shared libraries. By using these symbol tables on these platforms, the lt_dlopen and lt_dlsym functions can make your code appear to be loading and importing symbols, when in fact, the "load" function does nothing more than return a handle to the appropriate symbol table, and the "import" function returns the address of some code that's been statically linked into the program itself.

The ltdl library is, of course, not really necessary for packages that don't use manual run-time dynamic linking. But if your package does--perhaps by providing a plug-in interface of some sort--then you'd be well-advised to use the API provided by ltdl to manage loading and linking to your plug-in modules--even if you only target systems that provide good shared library services. Otherwise, your source code will have to consider the differences in shared library management between your many target platforms. At the very least, some of your users will have to put on their "developer" hats, and attempt to modify your code so that it works on their odd-ball platforms. (They may have to do so anyway, but when they finish, their work can then be incorporated into Libtool, so that everyone else can take advantage of their efforts.)

A word about the latest Libtool

The most current version of Libtool is 2.2. However, many popular GNU/Linux distributions are still shipping Libtool version 1.5, so many developers don't know about the changes between these two versions. The reason for this is that certain backward-compability issues were introduced after version 1.5 that make it difficult for GNU/Linux distros to support the latest version of Libtool. The upgrade probably won't happen until all (or almost all) of the packages they provide have updated their configure.ac scripts to properly use the latest version of Libtool.

This is somewhat of a "chicken-and-egg" scenario--if distros don't ship it, how will developers ever start using it on their own packages? So it's not likely to happen any time soon. If you want to make use of the latest Libtool version while developing your packages (and I highly recommend that you do so), you'll probably have to download, build and install it manually, or look for an updated Libtool package from your distribution provider.

Downloading, building and installing Libtool manually is really trival:

$ wget ftp.gnu.org/gnu/libtool/libtool-2.2.tar.gz

...

$ tar xzf libtool-2.2.tar.gz

$ cd libtool-2.2

$ ./configure && make

...

$ sudo make install

...

Be aware that the default installation location (as with most of the GNU packages) is /usr/local. If you wish to install it into the /usr hierarchy, then you'll need to use the --prefix=/usr option on the configure command line.

You might also wish to use the --enable-ltdl-install option on the configure command line to install the ltdl libraries and header files into your lib and include directories.

Adding shared libraries to Jupiter

Now that I've presented that background information, I will take a look at how I might add a Libtool shared library to the Jupiter project. First, consider what I might do with a shared library in Jupiter. As mentioned above, I might wish to provide my users with some library functionality that their own applications could use. I might also have several applications in my package that need to share the same functionality. A shared library is a great tool for both of these scenarios, because I get the benefits of code reuse and memory savings, as the cost of the memory used by shared code is amortized across multiple applications--both internal and external to my project.

I'll add a shared library to Jupiter that provides the print functionality I use in the jupiter application. I'll do this by having the new shared library call into the libjupcommon.a static library. Remember that calling a routine in a static library has the same effect as linking the object code for the called routine right into the calling application (or shared library, as the case may be). The called routine ultimately becomes an integral part of the calling binary image (program or shared library).

Additionally, I'll provide a public header file from the Jupiter project that will allow external applications to call this same functionality. By doing this, I can allow other applications to "display stuff" in the same way that the jupiter program "displays stuff". (This would be significantly cooler if I was actually doing something useful in jupiter!).

Using the LTLIBRARIES primary

Automake has built-in support for Libtool. The LTLIBRARIES primary is provided by code in the Automake package, not the Libtool package. This really doesn't qualify as a pure extension, but rather more of an add-on package for Automake, where Automake provides the necessary infrastructure for that specific add-on package. You can't access the LTLIBRARIES primary functionality provided by Automake without Libtool, because the use of this primary obviously generates make rules that call the libtool build script.

I state all of this here because it bothers me that you can't really extend the list of primaries supported by Automake without modifying the actual Automake source code. The fact that Automake is written in perl is somewhat of a boon, because it means that it's possible to do it. But you've really got to understand Automake source code in order to do it properly. I envision a future version of Automake whereby code may be added to an Automake extension file that will allow the dynamic definition of new primaries.

It's a bit like the old FOSS addage, generally offered to someone complaining about lack of functionality in a particular package: "It's open source. Change it yourself!" This is very often easier said than done. Furthermore, what these people are actually telling you is to change your copy of the source code for your own purposes, not to change the master copy of the source code. Getting your changes accepted into the master source base often depends more on the quality of your relationship with the current project maintainers than it does on the quality of your coding skills. I'm not complaining, mind you. I'm merely stating a fact that should not be overlooked when one is considering making changes to an existing open source software package.

So why not ship Libtool as part of Automake, rather than as a separate package? Because Libtool can quite effectively be used independently of Automake. If you wish to try Libtool by itself, then please refer to the GNU Libtool manual for more information. The opening chapters in that manual describe the use of the libtool script as a stand-alone product. It's really as simple as modifying your makefile commands such that the compiler, linker and librarian are called using the libtool script, and then modifying some of your command line parameters, as required by Libtool.

Public include directories

Earlier in this book, I made the statement that a project sub-directory named include should only contain public header files--those that expose a public interface in your project. I'm now going to add just such a header file to the Jupiter project: so, I'll create an include directory. I'll add this directory at the top-level of the project directory structure.

If I had multiple shared libraries, I'd have a choice to make: do I create separate include directories for each library in the library source directory, or do I add a single top-level include directory? I usually use the following rule of thumb to determine the answer to this question: if the libraries are designed to work together as a group, and if consuming applications generally use the libraries as a group, then I use a single top-level include directory. If, on the other hand, the libraries can be effectively used independently, and if they offer fairly autonomous sets of functionality, then I provide individual include directories in my project's library subdirectories.

In the end, it really doesn't matter much, because the header files for these libraries will be installed in entirely different directory structures than those in which they exist within your project. In fact, make sure you don't inadvertently use the same file name for headers in two different libraries in your project, or you'll probably have problems installing these files. They generally end up all together in the "$(prefix)/include" directory, although this default can be overridden with the pkginclude prefix.

I'll also add a directory for the new Jupiter shared library, called libjupiter. These changes require adding references to these new directories to the top-level Makefile.am file's SUBDIRS variable, and then adding corresponding makefile references to the AC_CONFIG_FILES macro in the configure.ac script:

$ mkdir include

$ mkdir libjup

$ echo "SUBDIRS = common include libjup src" \

> Makefile.am

$ echo "include_HEADERS = libjupiter.h" \

> include/Makefile.am

$ vi configure.ac

...

AC_PREREQ([2.61])

AC_INIT([Jupiter], [1.0], [bugs@jupiter.org])

AM_INIT_AUTOMAKE

LT_PREREQ([2.2])

LT_INIT([dlopen])

...

AC_CONFIG_FILES([Makefile

common/Makefile

include/Makefile

libjup/Makefile

src/Makefile])

...

The include directory's Makefile.am file is trivial, containing only a single line, wherein the public header file, libjupiter.h is referred to in an Automake HEADERS primary. Note that I'm using the include prefix on this primary. You'll recall that the include prefix indicates that files specified in this primary are destined to be installed in the $(includedir) directory (eg., /usr/local/include). The HEADERS primary is much like the DATA primary, in that it specifies a set of files that are to be treated simply as data to be installed without modification or pre-processing. The only really tangible difference is that the HEADERS primary restricts the possible installation locations to those that make sense for header files.

The libjup/Makefile.am file is a bit more complex, containing four lines, as opposed to the usual one or two lines:

libjup/Makefile.am

lib_LTLIBRARIES = libjupiter.la

libjupiter_la_SOURCES = jup_print.c

libjupiter_la_LIBADD = ../common/libjupcommon.a

libjupiter_la_CPPFLAGS = -I$(top_srcdir)/include \

-I$(top_srcdir)/common

Let me analyze this file line by line. The first line is the primary one, and contains the usual prefix for libraries. The lib prefix indicates that the referenced products are to be installed in the $(libdir) directory. I might also have used the pkglib prefix to indicate that I wanted my libraries installed into the $(prefix)/lib/jupiter directory. Here, I'm using the LTLIBRARIES primary, rather than the older LIBRARIES primary. The use of this primary tells Automake to generate rules that use the libtool script, rather than calling the compiler and librarian (ar) directly to generate the products.

The second line lists the sources that are to be used for the first (and only) product. The third line indicates a set of linker options for this product. In this case, I'm specifying that the libjupcommon.a static library should be linked into (become part of) the libjupiter.so shared library.

There's an important concept regarding the *_LIBADD variable that you should strive to understand completely: Libraries that are consumed within, and yet built as part of the same project, should be referenced internally, using relative paths within the build directory hierarchy. Libraries that are external to a project generally need not be referenced explicitly at all, as the $(LIBS) variable should already contain the appropriate "-L" and "-l" options for those libraries. These options come from attempts made by the configure script to locate these libraries, using the appropriate AC_CHECK_LIBS, or AC_SEARCH_LIBS macros.

The fourth line indicates a set of C preprocessor flags that are to be used on the compiler command line for locating the associated shared library header files. These options indicate, of course, that the top-level include and common directories should be searched by the pre-processor for header files referenced in the source code. In fact, here's the new source file, jup_print.c:

libjup/jup_print.c

#include <libjupiter.h>

#include <jupcommon.h>

int jupiter_print(char * name)

{

print_routine(name);

}

I need to include the shared library header file for access to the jupiter_print function's public prototype. This leads us to another general software engineering principle. I've heard it called by many names, but the one I tend to use the most is "The DRY Principle", which is an acronym that stands for Don't Repeat Yourself. C function prototypes are very useful, because when used correctly, they enforce the fact that the public's view of a function is identical to the package maintainer's view. So often, I've seen source code for a function where the source file doesn't include the header containing the public prototype for the function. It's easy to make a small change in the function or prototype, and then not duplicate it in the other location--unless you've included the public header file within the source file containing the function. Then, the compiler catches all such mistakes.

I need the static library header file because I call its function from within my public library function. Note also that I placed the public header file first--there's a good reason for this. Here is another general principle: by placing the public header file first in the source file, I can allow the compiler to check that the use of this header file doesn't depend on any other files in the project.

If the public header file has a hidden dependency on some construct (a typedef, structure or pre-processor definition) defined in internal headers like jupcommon.h, and if I include the public header file after jupcommon.h, then the dependency would be hidden by the fact that the required construct is already available in the translation unit when the compiler begins to process the public header file.

Next, I'll modify the jupiter application's main function so that it calls into the shared library instead of calling into the common static library:

src/main.c

#include <libjupiter.h>

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

jupiter_print(argv[0]);

return 0;

}

Here, I've changed the print function from print_routine, found in the static library, to jupiter_print, as provided by the new shared library. I've also changed the header file included at the top from libjupcommon.h to libjupiter.h.

My choices of names for the public function and header file were arbitrary, but based on a desire to provide a clean, rational and informational public interface. The name libjupiter.h very clearly indicates that this header file provides the public interface for the libjupiter.so shared library. I try to name library interface functions in such a way that they are clearly part of an interface. How you choose to name your public interface members--files, functions, structures, typedefs, pre-processor definitions, global data, etc--is up to you, but you should consider using a similar philosophy. Remember, the goal is to provide a great end-user experience.

Finally, the src/Makefile.am file must also be modified to use my new shared library, rather than the libjupcommon.a static library:

src/Makefile.am

bin_PROGRAMS = jupiter

jupiter_SOURCES = main.c

jupiter_CPPFLAGS = -I$(top_srcdir)/include

jupiter_LDADD = ../libjup/libjupiter.la

...

In this file, I've changed the jupiter_CPPFLAGS variable so that it now refers to the new include directory, rather than the common directory. I've also changed the jupiter_LDADD variable so that it refers to the new Libtool shared library object, rather than the libjupcommon.a static library. All else remains the same. Note that these changes are both obvious and simple. The syntax for referring to a Libtool library is identical to that referring to an older static library. Only the library extension is different. The Libtool library extension, .la stands for "libtool archive".

Take a step back for a moment: Do I actually need to make this change? No, of course not. The jupiter application will continue to work just fine the way it was originally set up--linking the code for the static library's print_routine directly into the application works equally well to calling the new shared library routine (which ultimately contains the same code). There is slightly more overhead in calling a shared library routine because of the extra level of indirection when calling though a jump table.

In a real project, you might actually leave it the way it was. Why? Because both public entry points, main and jupiter_print call exactly the same function (print_routine) in libjupcommon.a, so the functionality is identical. Why add the (slight) overhead of a call through the public interface? Well, you can take advantage of shared code. By using the shared library function, you're not duplicating code--either on disk, or in memory. Again, the DRY principle at work.

In this situation, you might now consider simply moving the code from the static library into the shared library, thereby removing the need for the static library entirely. Again, I'm going to beg your indulgence with my contrived example. In a more complex project, I might very well have a need for this sort of configuration, as such common code is often gathered together into static convenience libraries. Often, only a portion of this code is reused in shared libraries. I'm going to leave it the way it is for the sake of its educational value.

Reconfigure and build

Let me summarize where the project stands at this point. Since I've added a major new component to my project build system (Libtool), I'll add the -i option to the autoreconf command, just in case new files need to be installed:

$ autoreconf -i

$ ./configure

...

checking for ld used by gcc...

checking if the linker ... is GNU ld... yes

checking for BSD- or MS-compatible name lister...

checking the name lister ... interface...

checking whether ln -s works... yes

checking the maximum length of command line...

checking whether the shell understands some XSI...

checking whether the shell understands "+="...

checking for ...ld option to reload object files...

checking how to recognize dependent libraries...

checking for ar... ar

checking for strip... strip

checking for ranlib... ranlib

checking command to parse ...nm -B output...

...

checking for dlfcn.h... yes

checking for objdir... .libs

checking if gcc supports -fno-rtti...

checking for gcc option to produce PIC... -fPIC

checking if gcc PIC flag -fPIC -DPIC works...

checking if gcc static flag -static works...

checking if gcc supports -c -o file.o... yes

checking if gcc supports -c -o file.o... yes

checking whether ... linker ... supports shared...

checking whether -lc should be explicitly linked...

checking dynamic linker characteristics...

checking how to hardcode library paths...

checking whether stripping libraries is possible...

checking if libtool supports shared libraries...

checking whether to build shared libraries...

checking whether to build static libraries...

...

$

The first noteworthy item here is that Libtool adds significant overhead to the configuration process. I've only shown the output lines here that are new since I added Libtool. All I've added to the configure.ac script is the reference to the LT_INIT macro, and I've nearly doubled my configure script output. This should give you some idea of the number of system characteristics that must be examined to create portable shared libraries. Libtool does a lot of the work for you.

NOTE: In the following output examples, I've wrapped long output lines to fit publication formatting, and I've added blank lines between output lines for readability. I've also removed some unnecessary text, such as long directory names--both to increase readability and to shorten line lengths.

$ make

...

Making all in libjup

make[2]: Entering directory `.../libjup'

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=compile gcc

-DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I. -I../../libjup -I..

-I../../include -I../../common -g -O2

-MT libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo -MD -MP -MF

.deps/libjupiter_la-jup_print.Tpo -c

-o libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo

`test -f 'jup_print.c'

|| echo '../../libjup/'`jup_print.c

libtool: compile: gcc -DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I.

-I../../libjup -I.. -I../../include

-I../../common -g -O2 -MT

libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo -MD -MP -MF

.deps/libjupiter_la-jup_print.Tpo -c

../../libjup/jup_print.c -fPIC -DPIC

-o .libs/libjupiter_la-jup_print.o

libtool: compile: gcc -DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I.

-I../../libjup -I.. -I../../include

-I../../common -g -O2 -MT

libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo -MD -MP -MF

.deps/libjupiter_la-jup_print.Tpo -c

../../libjup/jup_print.c

-o libjupiter_la-jup_print.o >/dev/null 2>&1

mv -f .deps/libjupiter_la-jup_print.Tpo

.deps/libjupiter_la-jup_print.Plo

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=link gcc -g

-O2 ../common/libjupcommon.a -o libjupiter.la

-rpath /usr/local/lib libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo

-lpthread

*** Warning: Linking ... libjupiter.la against the

*** static library libjupcommon.a is not portable!

libtool: link: gcc -shared

.libs/libjupiter_la-jup_print.o

../common/libjupcommon.a -lpthread

-Wl,-soname -Wl,libjupiter.so.0

-o .libs/libjupiter.so.0.0.0

.../ld: ../common/libjupcommon.a(print.o):

relocation R_X86_64_32 against `a local symbol'

can not be used when making a shared object;

recompile with -fPIC

../common/libjupcommon.a: could not read symbols:

Bad value

collect2: ld returned 1 exit status

make[2]: *** [libjupiter.la] Error 1

...

That wasn't a very pleasant experience! It appears that I have some errors to fix. I'll take them one at a time, from top to bottom.

The first point of interest is that the libtool script is being called with a --mode=compile option, which causes libtool to act as a wrapper script around a somewhat modified version of a standard gcc command line. You can see the effects of this statement in the next two compiler command lines. Two compiler commands? That's right. It appears that libtool is causing the compile operation to occur twice.

A careful examination of the differences between these two command lines shows that the first compiler command is using two additional flags: "-fPIC" and "-DPIC". The first line also appears to be directing the output file to a ".libs" subdirectory, whereas, the second line is saving it in the current directory. Finally, both the STDOUT and STDERR output is redirected to /dev/null in the second line.

This double-compile "feature" has caused a fair amount of anxiety on the Libtool mailing list over the years. Mostly, this is due to a lack of understanding of what it is that Libtool is trying to do, and why it's necessary. Using various configure script command line options provided by Libtool, you can force a single compilation, but doing so brings with it a certain loss of functionality, which I'll explain here shortly.

The next line renames the dependency file from *.Tpo to *.Plo. Dependency files contain make rules that declare dependencies between source files and referenced header files. These are generated by the C preprocessor when the -MT compiler option is used. (And what better tool to know about such references than the one that actually processes them!) They're then included in makefiles so that the make utility can properly recompile a source file, if one or more of its include dependencies have been modified since the last build. This is not really germane to an examination of Libtool, so I'll not go into any more detail here, but check the GNU Make manual for more information. The point is that one Libtool command may (and often does) execute a group of shell commands.

The next line is another call to the libtool script, this time using the --mode=link option. This option generates a call to execute the compiler in "link" mode, passing all of the libraries and linker options specified in the Makefile.am file.

And finally, here is first problem--a portablity warning about linking a shared library against a static library. Specifically, this warning is about linking a Libtool shared library against a non-Libtool static library. You'll soon begin to see why this might be a problem. Notice also that this is not an error. Were it not for additional errors we'll encounter later, this library would be built in spite of this warning.

After the portability warning, libtool attempts to link the requested objects together into a shared library named "libjupiter.so.0.0.0". But here the script runs into the real problem--a linker error indicating that somewhere from within libjupcommon.a--and more specifically within print.o--an Intel object relocation cannot be performed because the original source file (print.c) was apparently not compiled correctly. The linker is kind enough to tell me exactly what I need to do to fix the problem. It indicates that I need to compile the source code using a "-fPIC" compiler option.

Now, if you were to encounter this error and didn't know anything about the "-fPIC" option, then you'd be wise at this point to open the man page for gcc and study it, before willy-nilly inserting compiler or linker options until the warning or error disappears, as many inexperienced programmers are wont to do. Software engineers should understand the meaning and nuances of every command line option used by the tools in their projects' build systems. Why? Because otherwise they don't really know what they have when their build completes. It may work the way it should--but if it does, it's simply by luck, rather than by design. Good engineers know their tools, and the best way to learn is to study error messages and their fixes until the problem is well-understood, before moving on.

So what is "PIC" code?

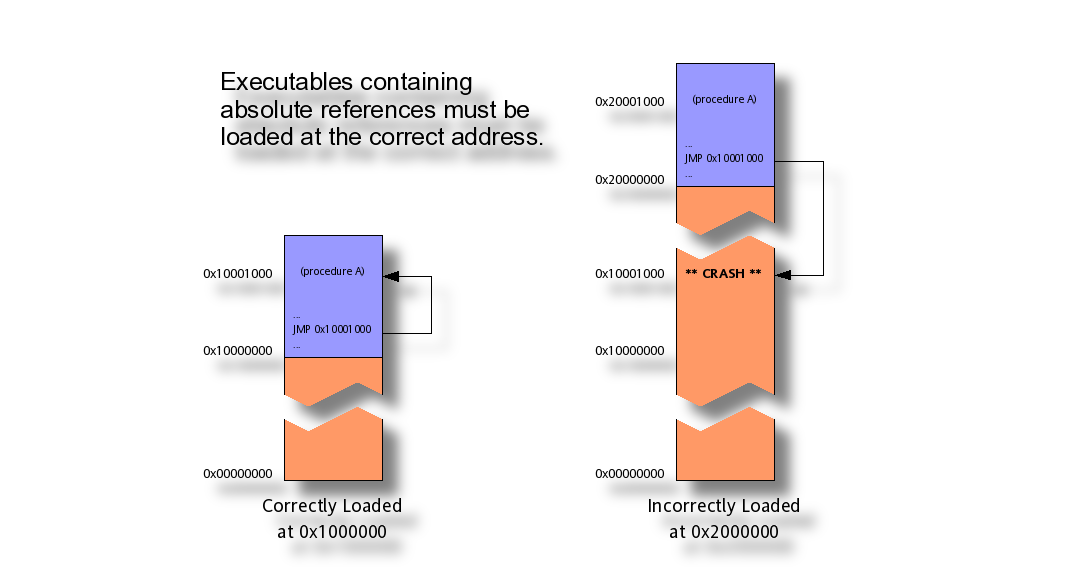

When operating systems create new process address spaces, they always load the executable images at the same memory address. This magic address is system-specific. Compilers and linkers know this, and they know what that address is on a given system. Therefore, when they generate internal references to function calls, for example, they can generate those references as absolute addresses. If you were somehow able to load the executable at a different location in memory, it would simply not work properly, because the absolute addresses within the code would be incorrect. At the very least, the program would crash when the it jumped to the wrong location during a function call.

Consider Figure 1 below for a moment. Given a system whose magic executable load address is 0x10000000, this diagram depicts two process address spaces within that system. In the process on the left, an executable image is loaded correctly at address 0x10000000. At some point in the code a "jmp" instruction tells the processor to transfer control to the absolute address 0x10001000, where it continues executing instructions in another area of the program. In the process on the right, the program is loaded incorrectly at address 0x20000000. When that same branch instruction is encountered, the processor jumps to address 0x10001000, because that address is hard-coded into the program image. This, of course, fails--often spectacularly by crashing, but sometimes with more subtle and dastardly ramifications.

That's how things work for program images. However, when a shared library is built for certain types of hardware (Intel x86 and x8664 included), the address at which the library will be loaded within a process address space cannot be known by either the compiler or the linker beforehand. This is because many libraries may be loaded into any given process, and the order in which they are loaded depends on how the _executable is built, not the library. Furthermore, who's to say which library owns location "A", and which one owns location "B"? The fact is, libraries may be loaded anywhere into a process where there is space for it at the time it's loaded. Only the operating system loader knows where it will finally reside--and then only just before it's actually loaded.

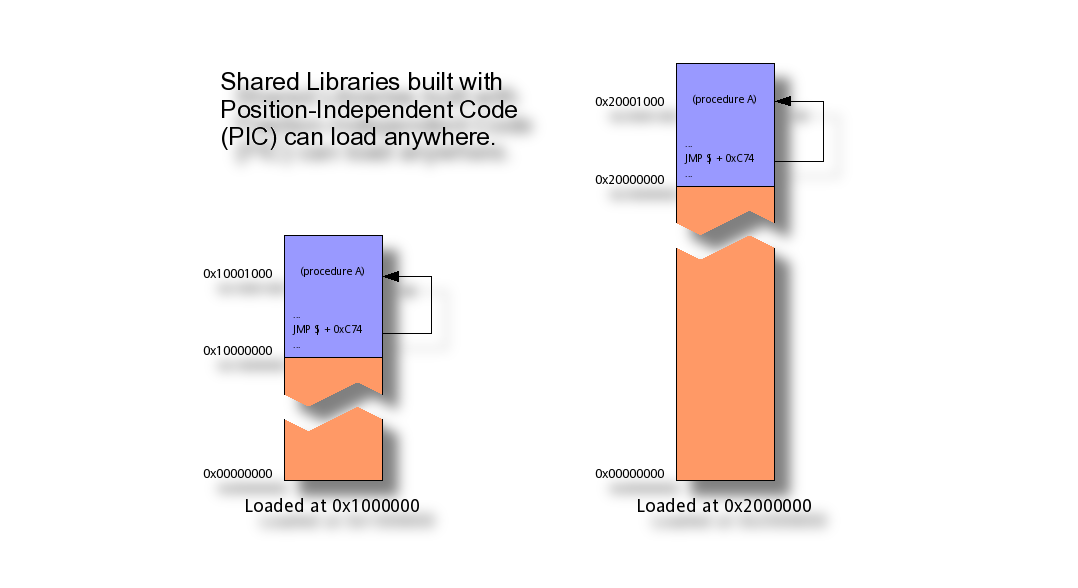

As a result, shared libraries can only be built from a special class of object file called "PIC" objects. PIC is an acronym which stands for "Position-Independent Code", and implies that references in the object code are not absolute, but relative. When the "-fPIC" option is used on the compiler command line, the compiler will use somewhat less efficient relative addressing in branching instructions. Such position-independent code may be loaded anywhere.

The diagram in Figure 2 below graphically depicts the concept of relative addressing, as used when generating PIC objects. When using relative addressing, regardless of where the image is loaded, addresses work correctly because they're always encoded relative to the current instruction pointer. In Figure 2, the diagrams indicate a shared library loaded at the same addresses, 0x10000000 and 0x20000000. In both cases, the DOLLAR SIGN ($) used in the JMP instruction represents the current instruction pointer (IP), so "$ + 0xC74" tells the processor that it should jump to the instruction starting 0xC74 bytes ahead of the current instruction pointer position.

There are various nuances to generating and using position-independent code, and you should become familiar with them all before using them, so that you can choose the option that is most appropriate for your situation. For example, the GNU C compiler also supports a "-fpic" option (lowercase), which uses a slightly quicker, but more limited mechanism to accomplish relocatable object code. Wikipedia has a very informative page on position-independent code (although I find its treatment of Windows DLLs to be somewhat less than accurate).

Fixing the jupiter "PIC" problem

From what you now understand, one way to fix my linker error is to add the "-fPIC" option to the compiler command line for the source files that comprise the libjupcommon.a static library. Try that:

common/Makefile.am

noinst_LIBRARIES = libjupcommon.a

libjupcommon_a_SOURCES = jupcommon.h print.c

libjupcommon_a_CFLAGS = -fPIC

And now I'll try the build again:

$ autoreconf

$ make

...

gcc -DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I. -I../../common -I.. -fPIC

-g -O2 -MT libjupcommon_a-print.o -MD -MP -MF

.deps/libjupcommon_a-print.Tpo -c

-o libjupcommon_a-print.o `test -f 'print.c' ||

echo '../../common/'`print.c

...

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=link gcc -g

-O2 ../common/libjupcommon.a -o libjupiter.la

-rpath /usr/local/lib libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo

-lpthread

*** Warning: Linking ... libjupiter.la against the

*** static library libjupcommon.a is not portable!

libtool: link: gcc -shared

.libs/libjupiter_la-jup_print.o

../common/libjupcommon.a -lpthread -Wl,-soname

-Wl,libjupiter.so.0 -o .libs/libjupiter.so.0.0.0

libtool: link: (cd .libs && rm -f libjupiter.so.0

&& ln -s libjupiter.so.0.0.0 libjupiter.so.0)

libtool: link: (cd .libs && rm -f libjupiter.so

&& ln -s libjupiter.so.0.0.0 libjupiter.so)

libtool: link: ar cru .libs/libjupiter.a

../common/libjupcommon.a

libjupiter_la-jup_print.o

libtool: link: ranlib .libs/libjupiter.a

libtool: link: (cd .libs && rm -f libjupiter.la

&& ln -s ../libjupiter.la libjupiter.la)

...

I now have a shared library, built properly with position-independent code, as per system requirements. However, I still have that strange warning about the portability of linking a Libtool library against a static library. The problem here is not in what I'm doing, but rather in the way in which I'm doing it. You see, the concept of PIC does not apply to all hardware architectures. Some CPUs don't support any form of absolute addressing in their instruction sets. As a result, native compilers for these platforms don't support a -fPIC option--it has no meaning for them.

If I tried (for example) to compile my code on an IBM RS/6000 system using the native IBM compiler, it would "hiccup" when it came to the -fPIC option because it doesn't make sense to support such an option on a system where all code is automatically generated as position-independent code. One way I could get around this problem would be to make the -fPIC option conditional in my Makefile.am file, based on the type of the target system, and the tools I'm using. But that's exactly the sort of problem that Libtool was designed to address! I'd have to account for all of the different Libtool target system types and tool sets in order to handle the entire set of conditions that Libtool already handles.

The way around this portability problem then is to let Libtool generate my static library as well. Libtool makes a distinction between static libraries that are installed as part of a developer's kit, and static libraries used only internally within a project. It calls such internal static libraries "convenience" libraries, and whether or not a convenience library is generated depends on the prefix used with the LTLIBRARIES primary. If the noinst prefix is used, then Libtool assumes that I want a convenience library because there's no point in generating a shared library that will never be installed. Thus, convenience libraries are always generated as static archives.

The reason for distinguishing between convenience libraries and other forms of static library is that convenience libraries are always built, whereas non-convenience static libraries are only built if the --enable-static option is specified on the configure command line (or conversely, if the --disable-static option is not specified).

Customizing Libtool with LT_INIT options

Default values for enabling or disabling static and shared libraries can be specified in the argument list passed into the LT_INIT macro in the configure.ac script. Have a quick look at the LT_INIT macrom which may be used with or without arguments. LT_INIT accepts a single argument, which is a white-space separated list of key words. The following key words are valid:

-

dlopen-- Enable checking fordlopensupport. This option should be used if the package makes use of the-dlopenand-dlpreopenLibtool flags, otherwise Libtool will assume that the system does not support dl-opening. This option is actually assumed by default. -

disable-fast-install-- Change the default behavior forLT_INITto disable optimization for fast installation. The user may still override this default, depending on platform support, by specifying--enable-fast-installtoconfigure. -

shared-- Change the default behavior forLT_INITto enable shared libraries. This is the default on all systems where Libtool knows how to create shared libraries. The user may still override this default by specifying--disable-sharedtoconfigure. -

disable-shared-- Change the default behavior forLT_INITto disable shared libraries. The user may still override this default by specifying--enable-sharedtoconfigure. -

static-- Change the default behavior forLT_INITto enable static libraries. This is the default on all systems where shared libraries have been disabled for some reason, and on most systems where shared libraries have been enabled. If shared libraries are enabled, the user may still override this default by specifying--disable-statictoconfigure. -

disable-static-- Change the default behavior forLT_INITto disable static libraries. The user may still override this default by specifying--enable-statictoconfigure. -

pic-only-- Change the default behavior forlibtoolto try to use only PIC objects. The user may still override this default by specifying--without-pictoconfigure. -

no-pic-- Change the default behavior oflibtoolto try to use only non-PIC objects. The user may still override this default by specifying--with-pictoconfigure.

NOTE: I've omitted the description for the win32-dll option, because it doesn't apply to this book.

Now, back to the Jupiter project. The conversion from an older static library to a new Libtool convenience library is simple enough--all I have to do is add LT to the primary name and remove the -fPIC option and the associated variable, as there were no other options being used in that variable. Note also that I've changed the library extension from .a to .la:

common/Makefile.am

noinst_LTLIBRARIES = libjupcommon.la

libjupcommon_la_SOURCES = jupcommon.h print.c

libjup/Makefile.am

...

libjupiter_la_LIBADD = ../common/libjupcommon.la

...

Now when I try to build, here's what I get:

$ autoreconf

$ ./configure

...

$ make

...

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=compile gcc

-DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I. -I../../common -I..

-g -O2 -MT print.lo -MD -MP -MF .deps/print.Tpo

-c -o print.lo ../../common/print.c

libtool: compile: gcc -DHAVE_CONFIG_H -I.

-I../../common -I.. -g -O2 -MT print.lo -MD -MP

-MF .deps/print.Tpo -c ../../common/print.c

-fPIC -DPIC -o .libs/print.o

...

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=link gcc -g -O2

-o libjupcommon.la print.lo -lpthread

libtool: link: ar cru .libs/libjupcommon.a

.libs/print.o

...

/bin/sh ../libtool --tag=CC --mode=link gcc -g -O2

../common/libjupcommon.la -o libjupiter.la

-rpath /usr/local/lib libjupiter_la-jup_print.lo

-lpthread

libtool: link: gcc -shared

.libs/libjupiter_la-jup_print.o

-Wl,--whole-archive

../common/.libs/libjupcommon.a

-Wl,--no-whole-archive -lpthread -Wl,-soname

-Wl,libjupiter.so.0 -o .libs/libjupiter.so.0.0.0

...

You can see that the common library is now built as a static convenience library because the ar utility is used to build libjupcommon.a. Libtool also seems to be building files with new and different extensions. A closer look will discover extensions such as .lo and .la. If you take a closer look at these files, you'll find that they're actually descriptive text files containing object and library meta data. Take a look at the common/libjupcommon.la file:

common/libjupcommon.la

# libjupcommon.la - a libtool library file

# Generated by ltmain.sh (GNU libtool) 2.2

#

# Please DO NOT delete this file!

# It is necessary for linking the library.

# The name that we can dlopen(3).

dlname=''

# Names of this library.

library_names=''

# The name of the static archive.

old_library='libjupcommon.a'

# Linker flags that can not go in dependency_libs.

inherited_linker_flags=''

# Libraries that this one depends upon.

dependency_libs=' -lpthread'

...

The various fields in these files help the linker--or rather the libtool wrapper script--to determine certain options that would otherwise have to be remembered by the developer, and then passed on the command line to the linker. For instance, the library's shared and static names are remembered here, as well as any other library dependencies required by these libraries. In this library, for example, I can see that libjupcommon.a depends on the pthread library. But, using Libtool, I don't have to pass a -lpthread option on the libtool command line because libtool can detect in this meta data file that the linker will need this, so it passes the option for me.

Making these files human-readable was a minor stroke of genius, as they can tell me a lot about my Libtool libraries, at a glance. These files are designed to be installed with their associated binaries, and in fact, the make install rules generated by Automake for Libtool libraries do just this.

The Libtool library versioning scheme

If you've spent any time at all working at the Linux command prompt, then you'll certainly recognize this series of executable and link names.

NOTE: There's nothing special about libz--I am merely using this library as a common example:

$ ls -dal /lib/libz*

... /lib/libz.so.1 -> libz.so.1.2.3

... /lib/libz.so.1.2 -> libz.so.1.2.3

... /lib/libz.so.1.2.3

If you've ever wondered what this means, then read on. Libtool provides a versioning scheme for shared libraries that has become prevalent in the Linux world. Other operating systems use different versioning schemes for shared libraries, but the one defined by Libtool has become so popular that people often associate it with Linux, rather than with Libtool. This is not entirely an unfair assessment because the Linux loader honors this scheme to a certain degree. But to be completely fair, it's Libtool that should be given the credit for this versioning scheme.

One interesting aspect of this scheme is that, if not understood properly, people can easily mis-use or abuse the system without intending to. People who don't understand this system tend to think of the numeric values as major, minor and revision, when in fact, these values have very specific meaning to the operating system loader, and must be updated properly for each new library version in order to keep from confusing the loader.

I remember a meeting I had at work one day several years ago with my company's corporate versioning committee. This committee's job was to come up with software versioning policy for the company as a whole. They wanted us to ensure that the version numbers incorporated into our shared library names were in alignment with the corporate software versioning standard. It took me the better part of a day to convince them that a shared library version was not related to a product version in any way, nor should such a relationship be established or enforced by them or anyone else.

Here's why. The version number on a shared library is not really a library version, but rather an interface version. The interface I'm referring to here is the application programming interface (API) presented by a library to the potential user--a programmer wishing to call functions in the interface. As the GNU Libtool manual points out, a program has a single well-defined entry point (usually called main, in the C language). But a shared library has multiple entry points that are generally not standardized in a widely understood manner. This makes it much more difficult to determine if a particular version of a library is "interface-compatible" with another version of the same library.

NOTE: The concept of "interface" goes much deeper in shared library versioning, referring to all aspects of a shared library's connections with the outside world. These connections include files and file formats, network connections and wire data formats, IPC channels and protocols, etc. When versioning a new public release of a shared library, all aspects of the library's interactions with the world should be taken into account.

Microsoft DLL versioning

Consider Microsoft Windows Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs). These are shared libraries in every sense of the word. They provide a proper application programming interface. But unfortunately, Microsoft has in the past provided no integrated DLL interface versioning scheme. As a result, Windows developers have often refered to DLL versioning issues (tongue-in-cheek, I'm sure) as "DLL hell".

As a fix to this problem, on Windows systems, DLLs can be installed into the same directory as the program that uses them, and the Windows operating system loader will always attempt to use the local copy first before searching for a copy in the system path. This alleviates a part of the problem because a specific version of the library can be installed with the package that requires it.

While this is a fair solution it's not a really good solution, because one of the major benefits of shared libraries is that they can be shared--both on disk and in memory. If every application has its own copy of a different version of the library, then this benefit of shared libraries is lost--both on disk and in memory.

Since the introduction of this partial solution, Microsoft hasn't paid much attention to DLL sharing efficiency issues. The reasons for this include both a cavalier attitude regarding the cost of disk space and RAM, and a technical issue regarding the implementation of Windows dynamic link libraries. Instead of generating position-independent code, Microsoft system architects chose to link DLL's with a specific base address, and then list all absolute address references in a base table in the image header. When a DLL can't be loaded at the required base address (because of a conflict with another DLL), then the loader "rebases" the DLL by picking a new base address and changing all of the absolute addresses referred to in the base table. Whenever a DLL is rebased in this manner, it can only be shared with processes that happen to rebase the DLL to the same address. The odds of accidentally encountering such a scenario--especially among applications with many DLL components--are pretty slim.

Recently, Microsoft invented the concept of the "Side-by-Side Cache" (sometimes referred to as "SxS"), which allows developers to associate a unique identification value (a GUID, in fact) with a particular version of a DLL installed in a system location. This location is named by the DLL name and version identifier. Applications built against SxS-versioned libraries have meta data stored in their executable headers that indicate the particularly versioned DLLs that they require. If the right version is found (by newer OS loaders) in the SxS cache, then they load it. Based on policy in the meta data, they can then revert to the older scheme of looking for a local and then a global copy of the DLL. This is a vast improvement over earlier solutions--providing a very flexible versioning system.

Given the fact that DLLs use the rebasing technique, as opposed to PIC code, the side-by-side cache is still a fairly benign improvement with respect to applications that manage dozens of shared libraries. SxS is really intended for system libraries that many applications are likely to consume. These are generally "based" at different addresses, so that the odds of clashing (and thus rebasing) are decreased.

Regardless, the entire based approach to shared libraries has the major drawback that the program address space may become fairly fragmented, as randomly chosen base addresses are honored throughout a 32-bit address space by the system loader. 64-bit addressing helps tremendously in this area, so you may find the side-by-side cache to be much more useful on 64-bit Windows systems.

Linux and other Unix-like systems that support shared libraries manage interface versions using the Libtool versioning scheme. In this scheme, shared libraries are said to support a range of interface versions, each identified by a unique integer value. If any aspect of an interface changes in any way between public releases, then it can no longer be considered the same interface. It becomes a new interface, identified by a new integer interface value. To make the interface versioning process comprehensible to the human mind, each public release of a library wherein the interface has changed simply acquires the next consecutive interface version number. Thus, a given shared library may support versions 2-5 of an interface.

Libtool shared libraries follow a naming convention that encodes the interface range supported by a particular shared library. A shared library named libname.so.0.0.0 contains the library interface version number, 0.0.0. these three values are respectively called the library interface current, revision and age values.

The current value represents the current interface version number. This is the value that changes each time a new interface version must be declared, because the interface has changed in any way since the last public release of the library. The first interface in a library is given a version number of "0", by popular convention.

Consider a shared library wherein the developer has added a new function to the set of functions exposed by this library since the last public release. The interface can't be considered the same in this new version as it was in the previous version because there's one additional function. Thus, it's current number must be increased from "0" to "1".

The age value represents the number of back-versions supported by the shared library. In mathematical terms, the library is said to support the interface range, current - age through current. In the example I just gave, a new function was added to the library, so the interface presented in this version of the library is not the same as that presented in the previous version. However, the previous version is still fully supported because the previous interface is a proper subset of the current interface. Thus, this library could conceivably be named "libname.so.1.0.1", where the range of supported interfaces is 1 - 1 (or 0) through 1, inclusive.

The revision value merely represents a serial revision of the current interface. That is, if no changes are made to a shared library's interface between releases--perhaps an internal function was optimized--then the library name should change in some manner, but both the current and age values would be the same, as the interface has not changed. The revision value is incremented to reflect the fact that this is a new release of the same interface. If two libraries exist on a system with the same name, and the same current and age values, then the operating system loader will always select the library with the higher revision value.

To simplify the release process for shared libraries, the GNU Libtool manual provides an algorithm that should be followed step-by-step for each new version of a library that is about to be publically released. I'll reproduce the algorithm verbatim here for your information:

- Start with version information of

0:0:0for each libtool library. [This is done automatically by simply omitting the-versionoption from the list of linker flags passed to thelibtoolscript.] - Update the version information only immediately before a public release of your software. More frequent updates are unnecessary, and only guarantee that the

currentinterface number gets larger faster. - If the library source code has changed at all since the last update, then increment

revision(c:r:abecomesc:r+1:a). - If any interfaces [exported functions or data] have been added, removed, or changed since the last update, increment

current, and setrevisionto 0. - If any interfaces have been added since the last public release, then increment

age. - If any interfaces have been removed since the last public release, then set

ageto 0.

Keep in mind that this is an algorithm, and as such it is designed to be followed step by step, as opposed to jumping directly to the steps that appear to apply to your case. For example, if you removed any API functions from your library since the last release, you would not simply jump to the last step and set age to zero. Rather, you would follow all of the steps properly until you reached the last step, and then set age to zero.

In greater detail: assume that this is the second release of a library, and that the first release was named libexample.so.0.0.0, and that one new function was added to the API during this development cycle, and one old function was deleted. The effect on this release of the library would be as follows:

- (n/a)

- (n/a)

libexample.so.0.0.0->libexample.so.0.1.0(library source was changed)libexample.so.0.1.0->libexample.so.1.0.0(library interface was modified)libexample.so.1.0.0->libexample.so.1.0.1(one new function was added)libexample.so.1.0.1->libexample.so.1.0.0(one old function was removed)

Why all the "hoop jumping"? Because, as I alluded to earlier, the versioning scheme is honored by the linker and the operating system loader. When the linker creates the library name table in an executable image header, it writes the versions of the libraries linked to the application along side of each entry in this table. When the loader searches for a matching library, it looks for the latest version of the library required by the executable. If the application was linked with version 0.0.0 of a particular library, but the user only has version 1.0.1 installed, the system will load it and use it because it's current and age values indicate that it supports the required version (0).

Note also that libname.so.0.0.0 can coexist in the same directory as libname.so.1.0.0 without any problem. Programs that need the earlier version (which supports only the later interface because of the deleted function) will properly and automatically have it loaded into their process address space, just as will programs that require the later version properly have the "1.0.0" version loaded.

One more point regarding interface versioning. Once you fully understand Libtool versioning, you'll find that even the above algorithm does not cover all possible interface modification scenarios. Consider, for example, version 0.0.0 of a shared library that you maintain. Now, assume you add a new function to the interface for the next public release. This second release is properly named version 1.0.1, because the library supports both interfaces 0 and 1. Just before the third release of the library, you realize that you didn't really need that new function after all, and so you remove it. Assume also that this is the only change made to the library interface in this release. The above algorithm would have this release named version 2.0.0. But in fact, you've merely removed the second interface, and are now presenting the original interface once again. Technically, this library should be properly named version 0.1.0, as it presents a second release of version 0 of the shared library interface.

Using libltdl to dlopen a shared library

Once again, I'm going to have to add some functionality to the Jupiter project in order to illustrate the concepts of this section. The goal here is to create a plug-in interface that the jupiter application can use to enhance the output.

Necessary infrastructure

Currently, jupiter prints "Hello, from jupiter!". (Actually, the name printed is more likely at this point to be a long ugly path containing some Libtool directory garbage and some derivation of the name "jupiter", but just pretend it prints "jupiter" for now.) I'm going to add an additional parameter to the common static library print routine, named "salutation". This parameter will also be a character string reference, and will contain the leading word or phrase--the salutation, as it were.

Here are the changes I have to make to the files in the common directory:

common/print.c

...

static void * print_it(void * data)

{

char ** strings = (char **)data;

printf("%s from %s!\n", strings[0], strings[1]);

return 0;

}

int print_routine(char * salutation, char * name)

{

char * strings[] = {salutation, name};

#if ASYNC_EXEC

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, 0, print_it, strings);

pthread_join(tid, 0);

#else

print_it(strings);

#endif

return 0;

}

common/jupcommon.h

#ifndef JUPCOMMON_H_INCLUDED

#define JUPCOMMON_H_INCLUDED

int print_routine(char * salutation, char * name);

#endif /* JUPCOMMON_H_INCLUDED */

And here are the changes I need to make to the files in the libjup and include directories:

libjup/jup_print.c

...

int jupiter_print(char * salutation, char * name)

{

print_routine(salutation, name);

}

include/libjupiter.h

...

int jupiter_print(char * salutation, char * name);

...

And finally, here are the changes I need to make to main.c in the src directory:

src/main.c

...

#define DEFAULT_SALUTATION "Hello"

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

char * salutation = DEFAULT_SALUTATION;

jupiter_print(salutation, argv[0]);

return 0;

}

To be clear, all I've really done here is parameterize the salutation in the print routines. That way, I can indicate from main what salutation I'd like to use. I've set the default salutation to "Hello", so that nothing will have changed from the user's perspective. The overall effect of these changes was benign. Note also that these are all source code changes. I've made no changes to the build system.

Adding a plug-in interface

Now, I can begin to discuss adding a plug-in interface to Jupiter. I'd like to make it possible to change the salutation displayed by simply changing a plug-in module. The code and build system changes required to add this functionality will be limited here to the src directory, and subdirectories thereof.

First, I need to define the actual plug-in interface. I'll do this by creating a new private header file in the src directory, called module.h:

src/module.h

#ifndef MODULE_H_INCLUDED

#define MODULE_H_INCLUDED

#define GET_SALUTATION_SYM "get_salutation"

typedef char * get_salutation_t(void);

char * get_salutation(void);

#endif /* MODULE_H_INCLUDED */

There are a number of interesting points about this header file. First, the preprocessor definition, GET_SALUTATION_SYM. This string represents the name of the function you need to import from the plug-in module. I like to define these in the header file, so that all of the information that needs to be reconciled co-exists in one place. In this case, the symbol name, the function type definition, and the function prototype must all be in alignment. While I could have simply allowed the caller to specify the string, defining the symbol name here allows me to change it later if I need to. As long as the caller used the definition I provided, s/he should be unaffected by a name change (of course, s/he'll have to recompile).

Another interesting point is the type definition: why should I provide one? If I don't, the user is going to have to invent one, or else use a complex type cast on the return value of the dlsym function. I provide it here for consistency. Finally, look at the function prototype. This isn't so much for the caller, as it is for the module itself. Modules providing this function should include this header file, so that the compiler can catch potential mis-spellings of the function name. Since all of this information must be in agreement, I simply define it all here together.

Doing it the "old-fashioned" way

For this first attempt, I'll use the dlopen/dlsym/dlclose interface provided by the Solaris, BSD and Linux libdl.so library. Then, in the next section, I'll convert this code over to the Libtool ltdl interface. To do this right, I need to add checks to the configure.ac script to look for both the libdl library and the dlfcn.h header file:

configure.ac

...

# Checks for header files (2).

AC_CHECK_HEADERS([stdlib.h dlfcn.h])

# Checks for libraries.

# Checks for typedefs, structures, and compiler...

# Checks for library functions.

AC_SEARCH_LIBS([dlopen], [dl])

...

echo \

"-------------------------------------------------

${PACKAGE_NAME} Version ${PACKAGE_VERSION}

Prefix: '${prefix}'.

Compiler: '${CC} ${CFLAGS} ${CPPFLAGS}'

Libraries: '${LIBS}'

...

These changes consist of adding the dlfcn.h header file to the list of files passed to the AC_CHECK_HEADERS macro, and adding a check for the dlopen function in the dl library. Note here that the AC_SEARCH_LIBS macro searches a list of libraries for a function, so this call goes under the section entitled, "Checks for library functions.", rather than the one entitled, "Checks for libraries."

To help me see which libraries I'm actually linking against, I've also added a line to the echo statement at the end of the file. The "Libraries:" line displays the contents of the LIBS variable, which is modified by the AC_SEARCH_LIBS macro.

NOTE: The LT_INIT macro actually already checks for the existence of the dlfcn.h header file, but I do it here explicitly, so it's obvious to observers that I wish to use this header file myself. This is a good rule of thumb to follow, as long as it doesn't negatively affect performance too much. In this case, I felt it was well worth the extra check. Besides that, the results of the check performed by LT_INIT is cached by autom4te, so it has little effect anyway.

Now it's time to actually add a new module. This requires several changes, so I'll make them all here now in the following command sequence:

$ cd src

$ mkdir -p modules/hithere

$ vi Makefile.am

SUBDIRS = modules

...

$ echo "SUBDIRS=hithere" > modules/Makefile.am

$ cd modules/hithere

$ echo "pkglib_LTLIBRARIES = hithere.la

> hithere_la_SOURCES = hithere.c

> hithere_la_LDFLAGS = -module \

> -avoid-version" > Makefile.am

$ vi hithere.c