What is this "Free Culture" thing? What is "Free Software"? And how do I get my work out there? If you're looking to participate in the "Commons", you'll need to get comfortable with the idea of free, public licenses and how to use them for your works. This won't be hard at all, especially with this short guide, but there are different traditions that have sprung up around different kinds of works.

Choosing a License

First of course, you'll need to decide what sort of license will fit both your project and your intentions for how you want to release it.

This used to be more complex, because there were so many competing options, but it's gotten much simpler because a few free-licenses have become extremely dominant, leaving most of the rest as historical footnotes. I'll present this as a flow chart and as a series of questions to answer about your project in case you're uncomfortable with reading flow charts.

First, you need to decide into which of three major categories your project best fits:

1) Is it an Aesthetic Work? This means it's something to be directly experienced and appreciated for what it is, not something you use as a tool. Most graphical arts, music, video, books, websites and so on fit into this category. If so, skip to "Licensing Aesthetic Works".

2) Is it a Computer Program? If so, start at "Licensing Computer Programs".

3) Is it a Hardware Design? In this case, go to "Licensing Hardware Designs".

There are a few edge cases to think about:

-

Graphic arts, sound effects, or music that are meant to be tightly integrated into computer programs (including games) are often licensed to match the program, so they should follow the "Computer Programs" track. (Some software, on the other hand is designed to keep the artwork separate which makes it easier to treat it as "Aesthetic Work").

-

TrueType or Type 1 fonts are generally sorted as "Computer Programs".

-

Written or graphical documentation is usually treated like "Aesthetic works".

-

Descriptions of how a thing is made are usually treated like "Aesthetic works".

-

Detailed plans which completely specify a design -- especially those that can be interpreted by machines (CAD/CAM files, gerber plots, VHDL) -- should be sorted as "Hardware Designs".

Licensing Computer Programs

Your next question is:

1) Do you want to impose a "copyleft" so that works derived from your work must also be under a free license?

There are different schools of thought on which is "more free": letting the user do whatever they want with the work (including monopolizing derivatives of it for profit) or ensuring that derivatives remain under a free license.

If you want a copyleft, go on to question 2. If not, then your best bet is the MIT/X11 license. See "Using Software Licenses" for how to apply it to your work.

2) If you do want a copyleft, a second question arises. Is your work a web-service?

When people deploy a web service on the internet, they are not distributing your work. Most copyleft licenses don't impose their copyleft requirements on such works

When people deploy a web service on the internet, they are not distributing your work. Most copyleft licenses, like the GPL, don't impose their copyleft requirements on such works because they aren't distributed. Some people regard this kind of use as a loophole or exploitation of GPL-licensed software.

If you are concerned about this, then your best choice is the "Affero General Public License" or AGPL. This license uses a simple requirement to keep the source code open -- it insists that any mechanism you provide for introspecting the source code from the running program be left intact. This allows users to access the source code through the web interface, including any derivations.

3) If not, then is your work a font?

Fonts are unusual for software in that they often need to be incorporated into documents when they are used (for example, in a PDF). This makes it possible to print the document correctly on a machine that doesn't already have the font installed. Under the GPL's rules, that would make the copyleft apply to the content of the document, which is not generally considered fair play.

For this reason, there is a simple Font Exception which can be used with the "GNU General Public License" (GPL). There are some other free font licenses, but the GPL with the font exemption is the simplest and most compatible.

4) Especially if your software is a programming library, do you want to allow proprietary ("non-free") programs to link to it?

Libraries often get incorporated into the software that calls them

Like fonts, libraries often get incorporated into the software that calls them. Even when the library is not included in the actual executable file, the GNU GPL forbids certain kinds of uses unless the program doing the calling is also a GPL program. Sometimes that's not what you want -- especially if you want your free-licensed library to become a standard solution for both free and non-free software.

For that case, there is the "GNU Lesser General Public License" or LGPL (it used to be called the "Library General Public Licenses" since it is mostly used for libraries). The LGPL still requires that direct derivatives are released under the LGPL (or GPL), but allows non-free programs which merely link to the library.

For other software (which means almost all software), you should use the "GNU General Public License" or GPL. The GPL is by far the most popular license for free software programs, and I highly recommend sticking to this for almost anything you write.

There is one additional nitpick, which is over whether to use GPL version 3 or not. I would say it's generally a good idea. However, some applications, notably the Linux kernel have remained at version 2 for both practical and ideological reasons. I won't go into detail here about those reasons, but for software intended to work closely with these, you'll most likely want to stick to GPL version 2. Otherwise, just use the most recent GPL.

For all of these cases, see "Using Software Licenses" for details on how to apply the license you chose.

Licensing Hardware Designs

Unlike computer programs, hardware designs provide information for how to manufacture products which are not themselves subject to copyright. If you don't care about copyleft, this won't matter, so question one...

1) Do you want any copyleft?

... is unchanged. And if you don't want it, then the MIT/X11 license is still a very good choice. You might also use the "Creative Commons Attribution" (CC By) license, which is explained under "Licensing Aesthetic Works". Either will do and the effect is similar (the CC license has a stronger set of terms for specifying correct attribution).

After that, the issue is similar to the problem with web services mentioned above. Someone can take a hardware design under the GPL, and -- without ever distributing it -- make improvements to the design and manufacture products based on it. Because they never distribute it, they have no obligation to have agreed to the license, and as a result, they do not have to abide by any source code (design) distribution terms you may have applied.

The legal theory is complex, but a few licenses do insist on making design data available to customers acquiring products made from the design or derivatives of it. I call this a "Production Copyleft." So, the next question is:

2) Do you want a production copyleft?

If you don't care about this point, then you can use the "GNU General Public License" (and see the section on "Using Software Licenses"). But if you do, then you want the "TAPR Open Hardware License" (TAPR-OHL) -- see the section on "Using Hardware Licenses".

Licensing Aesthetic Works

The economics of free-licensing aesthetic works are very different from those of free-licensing utilitarian works like programs or hardware designs. Artistic works are meant to be appreciated for what they are, not used to create other things. So, in general, it's pretty hard to implement "service models" as have been used with software and hardware.

The economics of free-licensing aesthetic works are very different from those of free-licensing utilitarian works like programs or hardware designs

One thing this has meant is that there is a much larger desire for "semi-free" licensing of aesthetic works. I would argue, however, that most of the use of these "semi-free" licenses is misguided and results in very unsatisfactory result for both creators and fans. I'm also going to suggest alternatives that will let you achieve the same ends with truly "free" licenses.

Creative Commons has provided a range of both "free" and "semi-free" licenses (six of these are important enough to mention here). All of them are used in the same way, so after you've chosen a license, you'll simply want to go to the section on "Using a Creative Commons" license for instructions that apply to all of them.

The first question is simply:

1) Do you plan to make money by selling copies of your work?

If you do not, then skip to question #3 below.

If you do plan to make money by selling copies, you still don't have to use a "non-free" license, because there are very simple business models for free works based on "Endorsement" that avoid much of the hassle and enmity of the older "Monopoly" strategy. Some examples of this have been very successful. So:

2) Do you want to use an "Endorsement" model or a "Monopoly" model to provide a "reason to buy" your official copies?

If you choose the "Endorsement" approach, then go on to question #3.

If you opt for the "Monopoly" model, then skip to "Monopoly Model Creative Commons Licenses" for question #5.

Which brings us to:

3) Is your work "politically dangerous"?

I'm sure that sounds weird. And actually it is. But almost every reason you might have for wanting to prevent your work from being altered is better served by use of the Creative Commons Attribution requirement, which allows you to simply insist on the removal of your name from any modified version you don't approve of. Only if the situation were such a political hot-button issue that such common sense would not prevail really provides a sufficient cause to consider the "NoDerivatives" option. And of course, due to fair use, there are still quite a few ways in which your work could be used, referenced, or parodied.

Almost every reason you might have for wanting to prevent your work from being altered is better served by use of the Attribution requirement, which allows you to simply insist on the removal of your name from any modified version you don't approve of

In particular, the most common real reason why artists consider an ND license is the desire to avoid seeing inferior derivatives of their work spread about by careless or less-skilled artists. But this is most easily dealt with by removing your name from the work, as the Attribution clause allows (it does provide the right of non-attribution to disclaim a derivative you don't like as well).

But if all of this doesn't sway you, then you may want to use the "non-free" "Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives" (CC By-ND) license.

Otherwise, your next question is simply:

4) Do you want to impose a copyleft so that people who make derivatives from your work must also release their work under a free license?

If "yes", then you'll want to use the "Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike" license (CC By-SA). This is by far the most popular free license for aesthetic works, and I highly recommended it.

What most artists are afraid of when they talk about "exploitation" is that someone will make lots of money by charging for access to their work and they won't see a dime. This bothers many artists even more than the prospect of no one making any money from it. And as a result, they often mistakenly think that a "NonCommercial" license is what they need.

But as Nina Paley likes to say, "the problem is not commerce, the problem is monopolies." This kind of exploitation can't happen unless the exploiter manages to get some kind of monopoly over distributing your work -- and the ShareAlike clause guarantees that they can't do that.

However, even a simple ShareAlike requirement introduces some administrative overhead and there are some possible conflicts. If you really don't want this hassle and you don't care about the possibility of "exploitation" by people incorporating your work into proprietary works, then your answer to #4 is "no", and you'll want to choose the "Creative Commons Attribution Only" license (CC By).

Lastly, if you don't even care about Attribution, and want to avoid all hassle with the work, you can assign it to the public domain, using an assertion notice like the "Creative Commons Public Domain Assertion" (CC0).

Monopoly Model Creative Commons Licenses (Non-Free)

Licenses that we consider "free" create a kind of parity between all users of the work, so that who owns the copyright is much less important than what the public license allows anyone to do with the work. This is a strong incentive for people to share their labor to improve your work, since, in a sense, it becomes their work too.

Licenses that we consider "free" create a kind of parity between all users of the work, so that who owns the copyright is much less important than what the public license allows anyone to do with the work

Non-free licenses (and the semi-free Creative Commons "NonCommercial" or "NoDerivatives" licenses) break this parity, putting the originator of the work in a position of unique power over it. This greatly reduces the desire of others to contribute to it, since they can't claim the work they put into it. That's why such licenses don't create a viable "commons" (they can create small fan-sharing communities, but these lack the vibrancy of those surrounding free works).

Historically, this has been regarded as a necessary evil if you want to make money from your work. This argument is becoming weaker all the time as new business models are developed to make money from truly free work, but it is the traditional way of making money from copyrighted works. So the Creative Commons has provided licenses which protect this business model, but still provide some of the freedoms that many of your fans want.

5) Do you want to allow fan works?

If you don't, you might as well use the "Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives" (CC By-NC-ND) license, and make it clear that you are not authorizing derivatives. This is the most restrictive Creative Commons license and means fans can only share your work exactly as it is. Basically it legalizes file-sharing, and nothing else.

Otherwise, we are back to...

6) If fans make works, do you want to allow them to use the NoDerivatives clause?

This is the only difference between using a "Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial" license (CC By-NC) and using a "Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike" (CC By-NC-SA) license.

CC By-NC-SA is not truly a "ShareAlike" license, because the "NonCommercial" clause imposes asymmetrical terms on your fans. You are claiming for yourself any commercial uses, and forbidding them from making revenue even on their own work if it derives from yours in any way specified by copyright (which is quite broad). So the use of the term "SA" is a bit misleading here.

CC By-NC-SA is not truly a "ShareAlike" license, because the "NonCommercial" clause imposes asymmetrical terms on your fans

Neither CC By-NC-SA works nor any derivatives made from them can be released as part of any free culture project under the CC By-SA license. The same applies to CC By-NC works.

The only thing that the "SA" module does in the NonCommercial case is that it restricts your fans from using a "NoDerivatives" clause on their fan works derived from your work (Without it, they may release under CC By-NC, CC By-NC-ND, or CC By-NC-SA).

Using Software Licenses

Because software source code is large, highly structured, and mostly unseen, the practice for licensing software has been very thorough and explicit. The recommended steps are:

- Include the entire license in a separate text file in the source file tree

- Add text to the beginning of each source code text file with an assertion of the license

- Provide links to the online version of the license as well

- Include a notice in runtime output if appropriate

The Free Software Foundation's license pages provide boilerplate and instructions for applying their licenses. Briefly, you need to include boilerplate text in each source code file of your software. The template below will serve for GPL, AGPL, or LGPL licenses:

<PACKAGE-NAME>

Copyright (C) <YEAR> <AUTHOR-NAME>

This file is part of <PACKAGE-NAME>.

<PACKAGE-NAME> is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify

it under the terms of the <LICENSE> as published by

the Free Software Foundation, [either] version <VERSION> of the License[, or

(at your option) any later version].

<PACKAGE-NAME> is distributed in the hope that it will be useful,

but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of

MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the

<LICENSE> for more details.

You should have received a copy of the <LICENSE>

along with <PACKAGE-NAME>. If not, see <http://www.gnu.org/licenses/>.

Of course, you will need to substitute for the fields below, indicated by <> in the above template:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| PACKAGE-NAME | Name of the whole program |

| YEAR | Copyright year of the work (the whole program) |

| AUTHOR-NAME | Name of the author (you) or copyright holder |

| LICENSE | The full name of the particular license chosen |

| VERSION | The particular version of the license to use |

The text in [] brackets is optional. Without it, only the particular version of the license listed will apply unless you later giver permission for re-licensing. Allowing later versions means that users can automatically use your work under the terms of a later license if the Free Software Foundation released another version.

The entire text of the GPL, LGPL, and AGPL can be acquired from the Free Software Foundation web page, which also contains the FSF's version of these instructions. The MIT/X11 license is readily available from the Open Source Initiative.

For fonts, boilerplate for a special exception is usually added. This permits the font to be included in documents without the copyleft being interpreted as affecting the document contents (the particular wording makes this exception compatible with the GPL itself):

As a special exception, if you create a document which

uses this font, and embed this font or unaltered portions

of this font into the document, this font does not by

itself cause the resulting document to be covered by the

GNU General Public License. This exception does not

however invalidate any other reasons why the document

might be covered by the GNU General Public License. If

you modify this font, you may extend this exception to

your version of the font, but you are not obligated to do

so. If you do not wish to do so, delete this exception

statement from your version.

Using the TAPR Open Hardware License

Using the TAPR Open Hardware License is very similar to using the GPL for software, so you should probably read the previous section as well. Hardware designs are also usually complex file hierarchies, so again, it makes sense to include the entire license and to place notices in each source file where the data format permits it.

Software is very much based on readable text-formats where space for notices is not a problem, but hardware files are in a variety of formats which may be less forgiving (the same problem that exists for multimedia files). So the TAPR-OHL suggests a much briefer boilerplate for inclusion in each file (or at least in each file that permits it):

Licensed under the TAPR Open Hardware License (www.tapr.org/OHL)

One of the copyleft terms in the TAPR-OHL allows for email notifications, so an additional file, "CONTRIBS.txt" is recommended for providing email addresses which require notifications under the copyleft terms.

Simple copyright notices (optionally including a reference to the "TAPR Open Hardware License" or "TAPR-OHL") should be provided in a visible form in artwork that defines the name plates or internal markings to be included in the final product. For example, the screenprint layer or trace layer of a printed circuit board might include this. CAD or schematic drawings should include such a notice in the title box.

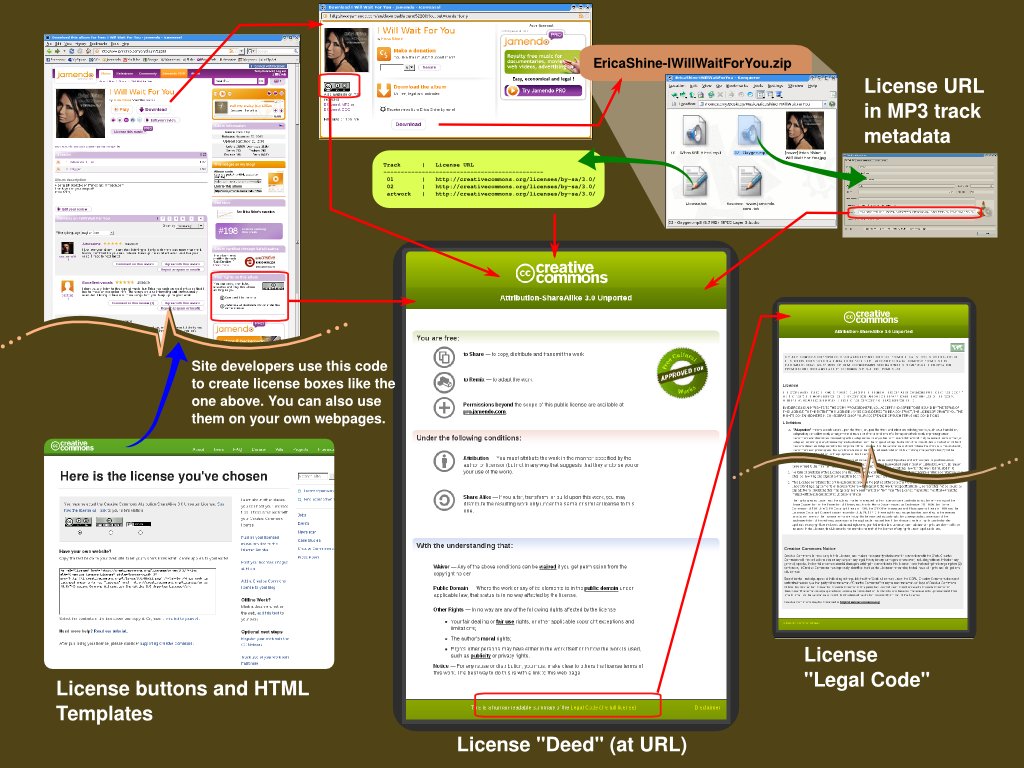

Using Creative Commons Licenses

Many of the aesthetic works for which the CC licenses are intended are not very amenable to including entire legal documents. They are also often broken up into individual files. So embedded metadata is much more useful (though not required).

Instead of including the entire legal document, Creative Commons prefers that you simply use a URL for the license you meant to invoke

The recommendations of the Creative Commons, therefore, are somewhat different. Instead of including the entire legal document, CC prefers that you simply use a URL for the license you meant to invoke. You'll notice that the linked page is the "license deed" -- an informal description of how the license works. The actual text is available as the "legal code" accessible from a link on that page. A small text link at the bottom of the page saying "Use this license for your own work" will also take you to a licensing page that contains nice graphic button icons and HTML templates to mark your licensed work on the web (this one of the nicest things about the CC licenses, because it provides clear and consistent marking for users).

Here's a full breakdown of the relevant CC links for the six licenses suggested here, plus the CC0 "public domain assertion" (which is not legally a license):

| CC LICENSE | Deed | Legal Code | Buttons and Templates |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC By-SA | deed | legal | code |

| CC By | deed | legal | code |

| CC By-NC | deed | legal | code |

| CC By-NC-SA | deed | legal | code |

| CC By-NC-ND | deed | legal | code |

| CC By-ND | deed | legal | code |

| CC 0 | deed | legal | generator |

The actual links follow a simple pattern: "by" represents the "Attribution" module; "sa" represents the "ShareAlike" module; "nc" represents the "NonCommercial" modules; and "nd" represents the "NoDerivatives" module. The modules are linked by hyphens.

In addition, each license also has regionalized versions with particular details relevant to each jurisdiction. The top-level "unported" licenses are meant to apply internationally under the Berne Copyright Convention terms. If a local version exists for your reason, you're probably better off to use it as its terms will be more readily understood and enforced in your jurisdiction. However, the licenses are designed explicitly to be compatible with each other, so what jurisdiction you choose has little legal significance and does not block sharing to other jurisdictions.

Please note, however, that if you are creating a complex archive file for release, that it's still a good idea to include the entire text of the Creative Commons license (copying and paste from the "legal code" for your license), even though CC itself doesn't encourage this practice. This is useful in case the recipient does not have easy access to the Creative Commons website.

Codifying Freedom

Freedom is a complex concept. It's really a balance of power between individuals, so that each feels that they have power over their own actions, without needing to control others. Licenses that are designed to maximize freedom do so by having each party agree to give up the ability to control others in exchange for not being controlled themselves. Different domains and different ideologies sometimes differ on exactly which balance is "most free" and this accounts for some of the diversity of licenses you'll find out there.

This document represents my own idea of what the "best practices" are for licensing different kinds of work. In particular, I think the reasoning behind choosing Creative Commons licenses is frequently obfuscated by the way it's usually presented, so I hope this clears it up some. Of course, you'll find other opinions out there.

Licensing Notice

This work may be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, version 3.0, with attribution to "Terry Hancock, first published in Free Software Magazine". Illustrations and modifications to illustrations are under the same license and attribution, except as noted in their captions (all images in this article are CC By-SA 3.0 compatible).