The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement, but the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth—Niels Bohr

Material products are getting “smarter” in that more and more of the value of a material product is contained in the information it carries, rather than in its material substance. R. Buckminster Fuller called this process “ephemeralization”[1], and it is one means by which the economics of matter—predicated on the conservations of mass and number—are becoming sidelined by the properties of information. Furthermore, both the capital and marginal cost of making products has trended consistently and rapidly down as manufacturing tools become both cheaper and more versatile, so that the capital cost of an object is increasingly not in the capital equipment required to manufacture it, but in the effort required to design it.

Both the capital and marginal cost of making products has trended consistently and rapidly down as manufacturing tools become both cheaper and more versatile

Software is only the most extreme example, for which both the “Gnu Manifesto”[2] and the “The Cathedral and the Bazaar”[3] claim that the system of copyright monopoly has begun to behave pathologically, and this has been the basis for the free software movement. Raymond’s arguments in “The Magic Cauldron”[4], suggest that this behavior, and the resulting economic success of free-licensing does not truly rely on zero cost of replication, as even software has non-zero replication costs.

Yet, the business model of masquerading an information product as a matter product—by legally controlling the “uncomfortable” property of free replication—has been remarkably successful for a very long time. This suggests that we should consider whether the converse is possible: can matter-based products be masqueraded to act more like information products—eliminating (or hiding) the uncomfortable property of costly replication ? In other words, can we create a bazaar for free-licensed hardware design information and a matter product manufacturing economy which supports it? And can we do it without poisoning the free-design process itself? If so, we might be able to port the high utility, rate of innovation, and low costs found in the free software community to community-based hardware projects—an extremely attractive possibility.

Can we create a bazaar for free-licensed hardware design information and a matter product manufacturing economy which supports it?

What do we want to keep?

The principle reasons for wanting to emulate free software’s “bazaar” development model are those explored in “The Magic Cauldron”, which identifies the important principles of self-selection and self-management, which are active whenever participation in a project is driven by personal interest rather than profit-seeking.

Raymond breaks management duties into: “defining goals”, “monitoring”, “motivating”, “organizing”, and “marshalling resources”, and shows that when self-selection applies, market forces acting on the participants account for the self-managing nature of bazaars, leaving no need for explicit managers: goals are personal and set before contributors even arrive at a project, motivation is for the project to work so that it will suit developers’ own needs, and motivated people don’t need monitoring. Organization is derived as a special case of goal-setting and a lack of personal conflict over competing ideas, which is natural when no gain other than project success is sought by “competing” parties. This situation is likely to persist so long as there is no material gain to motivate contributors, since “interest” will then remain the primary motivator. All of these properties are as applicable to hardware design as to software.

For the final point, “marshalling resources”, however, hardware is going to present special challenges, since hardware design will require the construction of prototypes, experimental apparatus, testing services, and manufacturing expenses. So, the most serious obstacle to overcome is payment for costs without interference with the interest-motivation of developers:

- A means must be found to offset the materials and manufacturing costs associated with free-licensed hardware prototypes, experimental apparatus, and finally, manufacturing cost.[6]

Hardware design will require the construction of prototypes, experimental apparatus, testing services, and manufacturing expenses

Other requirements for success include the maintenance of a healthy effective bazaar size. This can be a problem for the much smaller hardware developer communities, largely due to a lack of exposure to the tools for manufacturing and design, and there are four strategies that can be used to solve this part of the problem:

- Make the bazaar more efficient at attracting, retaining, and collecting contributions from developers. This makes a larger bazaar size, despite a smaller community. Essentially, it must be easier to contribute.[5]

- Make development reduce loss by more efficient and complete archiving, and above all, usefully cataloging archived data so that it can be efficiently retrieved when needed.[7]

- Make more and better collaborative design tools available to the users as free software so that more would-be developers have access to them, and are made aware of the benefits of free-licensing.

- Actively train users on the tools and methods needed to become an effective developer—encourage growth in the community by turning more users and other interested parties into developers. This can only be pursued by active contributions.

Laying down the law

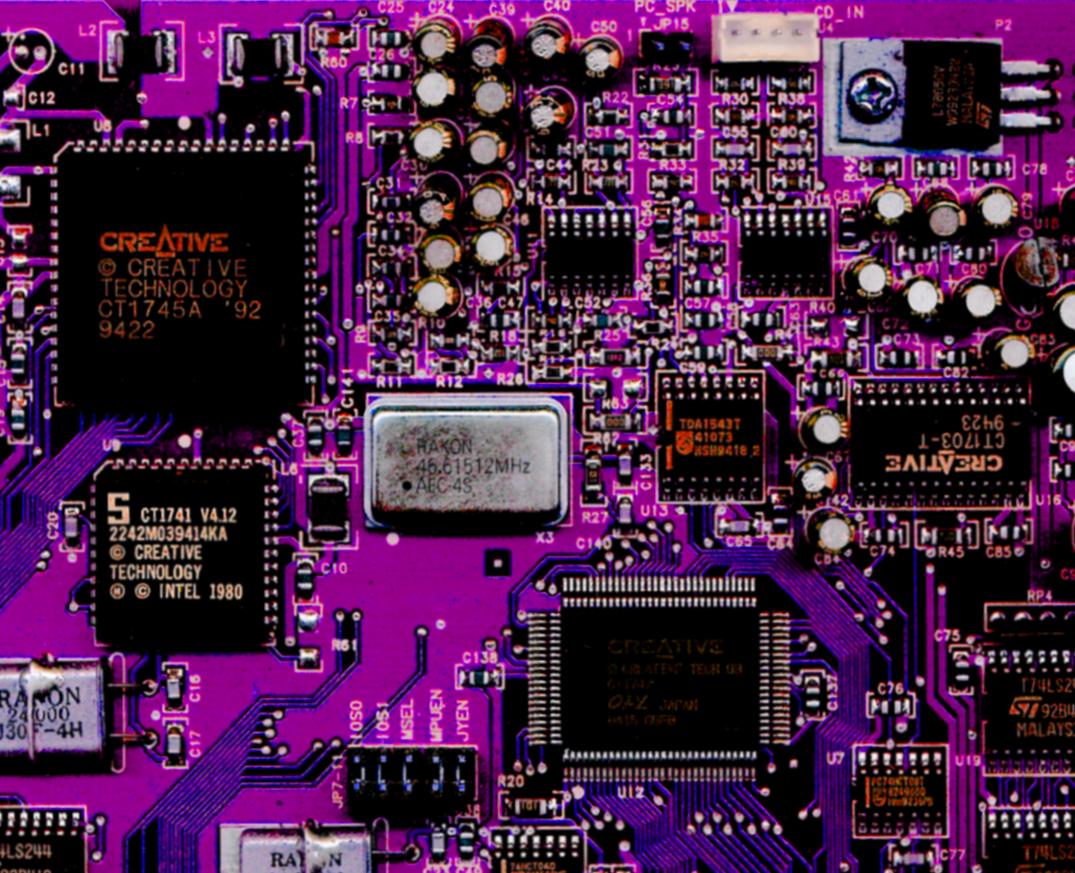

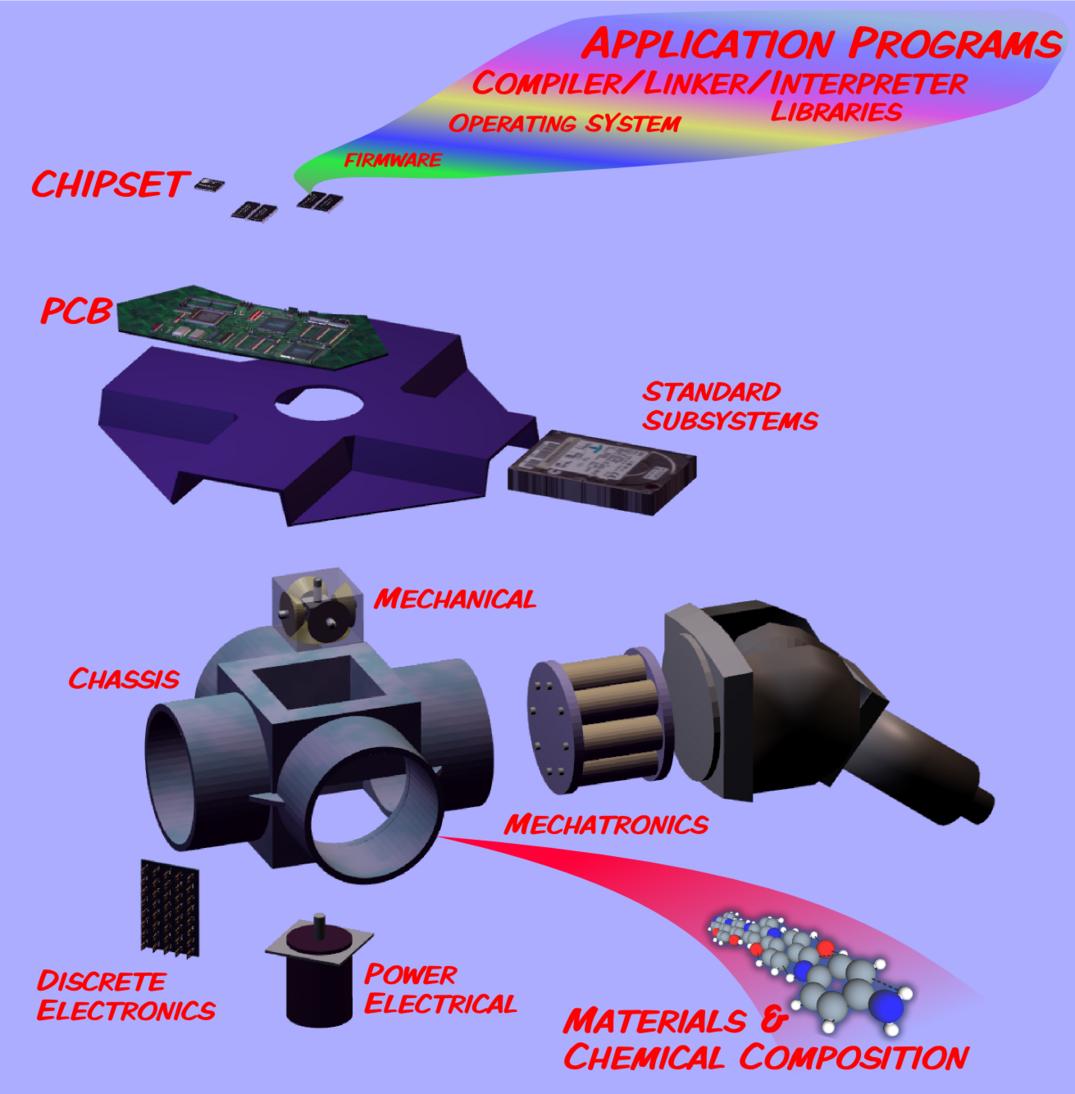

Almost no piece of hardware is totally “free”, because it invariably uses proprietary products at some depth. With software, a hard legal line can be drawn, but hardware introduces a fuzzy area that needs to be understood and controlled. As Figure 2 attempts to show, we have many different layers to consider: Program, Firmware, PAL devices, PCB design, Core-level, Chip-level, and even discrete component level. It’s less of a problem for mechanical designs, but electromechanical components are frequently single-source, and it may therefore be difficult to replace them in the future. All of which argues for the importance of commoditized subsystems to support top-level free designs.

In general, we want the depth of free design elements to increase, but we have to be able to tolerate considerable transition time, especially if we want to coexist peacefully with a more conventional manufacturing economy. Just as free programs need free libraries, free machines need free electronics and ultimately free components. However, for pragmatic projects, this will always be a design-trade—sometimes it will be expedient to use components that are proprietary to get the job done, and we will be accepting the risk that those designs will become impossible in the future due to supplier monopolies (the use of “commodity” PCs is an example).

Just as free programs need free libraries, free machines need free electronics and ultimately free components

Even the LART, which is often held up as the prototypical free hardware computer, suffered from this problem: the particular ARM-series CPU used in the LART design was discontinued[8]. When this happened, implementors were stuck with trying to find existing surplus or used components, or coming up with a new design to accomodate newer parts.

Preventing this kind of problem—or even providing economic motivation to phase it out—will present a more difficult legal problem than for software. Attempts to legally encode a definitive “Free Hardware License”, of the stature of the Gnu GPL, have been encumbered by this complexity, although the draft “Open Hardware General Public License”9 is an interesting attempt. Today, however, the Open Cores website promotes using the unmodified GPL or BSD licenses for free-licensed hardware designs.

The love of money is the root of all evil

Injecting money into a development or innovation process carelessly can be amazingly destructive, much as U.S. President Eisenhower, in his closing address to the American people, warned:

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity.

So, it shouldn’t really come as a shock that attempts to introduce money to free-licensed development have not been more successful.

In Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)

In a free matter economy, free-design data is produced in the same way as free software is today, and the manufacturing process is managed by the end user. That either means building it yourself, or contracting a manufacturing service provider to do it for you. But either way, the manufacturing process is decentralized and localized near the end-user.

This is driven by the market forces described in this series, but there is another reason for it: in the future, transportation costs will be a much bigger factor. I don't just mean that oil prices are rising, though they certainly are. No, the point is that we are on the verge of becoming an interplanetary society. Once we do that, however, the convenient drop-ship-to-anywhere style of our present global economy will break down. Instead, we'll be trying to find ways to “live off the land”.

This is the core point of Robert Zubrin's “Mars Direct” plan[21]. It's also a key factor in plans for settling on the Moon. Either way, the need to avoid the enormous expense of interplanetary transport for any products that can be made on the spot is great. In the acronym-happy space community, this idea is known under the mouthful “In Situ Resource Utilization” or ISRU. It presents considerable obstacles for the conventional manufacturing-based, product-oriented exchange economy that we have now. But the proposed manufacturing-service, free-design-information economy described in this series would have an opportunity to flourish in this context.

Grants

Grants provide money in advance, when it is most needed, both to provide for the material needs of the project and to pay researchers for their time, making them the most obvious way to fund any public good. We’ve funded university and institutional research this way for ages. Many precursors of free software products got started like this, including the code that became the Unix family of operating systems. Clearly this system can and does work.

However, grant money, once given, is extremely hard to get back. So when a person applies for a grant they must endure a gauntlet of tests, intended to prove to the granting agency that that person is willing and able to fulfill the promise they make in their proposal. If a grant is received, will the project be completed? How much money will it cost? Real research is full of unexpected set-backs and cost-overruns. Real researchers are full of optimism and unrealistic deadlines. The skills for research, development, logistics, and management are rarely found all in one person—good scientists rarely make good accountants, let alone good receptionists.

This encourages the granting agency to be very selective and take few risks with whom they fund. Researchers must have a proven professional background, track-record of honesty, and a reputation to protect. This is why funding by grants requires the use of large government, foundation, and university bureaucracies, and only the professionals who have climbed the career ladder to positions in these organizations have a serious chance of benefitting from them. The “solitary inventor” is indeed dealt out of this game, just as Eisenhower predicted.

Real research is full of unexpected set-backs and cost-overruns. Real researchers are full of optimism and unrealistic deadlines

Attempts to extend grant systems to less certified individuals have drawn limited funds from donors, and would-be researchers are understandably reluctant to make the kinds of promises they must make to receive a grant. So, it appears that little can be done to make grants work better for free-licensed hardware designs.

Free hardware pioneers

I present free hardware in a largely theoretical way here, but there already are free hardware design communities, built using existing tools for online collaboration. Here are just three examples:

One of the most exciting proofs-of-principle was the LART project [8], which developed an ARM-based single-board computer to be used in multimedia applications. LART was developed by a company that had a need for such a system in one of their projects, and did not want to be dependent on a vendor-supplied board to do the job. By opening the source for the LART, they were able to build a community around the LART design. This also allowed for them to collectively bargain for runs of PCBs, which are much cheaper to manufacture in larger quantity.

Another influential site is Open Cores [22], which develops “Open Intellectual Property (IP) Cores” for the manufacture of LSI microchips. An “IP Core” of a chip is a collection of design elements which can be combined with other elements in the production of customized integrated circuits. It can be regarded as the hardware source-code for a chip. This really makes sense as a pioneer project, since ICs are among the most ephemeralized hardware technologies we have.

Artemis Society International[23] is a project to design a complete technology chain for establishing a permanent Human presence on the moon, based on the tourist economy. They want to create a small habitat on the moon to be sold as a hotel in a kind of “adventure tourism” package. They are making use of both government-funded development for the International Space Station (and previous projects) and equipment designed and manufactured by independent space companies, like SpaceHab, whose extensible module-system figures prominently in the Artemis design.

Prizes

Prizes have been proposed as a much better solution than grants, and it’s not hard to see why: With a prize, the donor does not have to try to predict in advance who can achieve the proposed goal, nor how it will be achieved. Likewise, applicants don’t have to prove anything to the donor about their past performance—they just have to step up to the task at hand and do it. That means there’s no “artificial” barrier to entry. The success of the Ansari X-Prize, recently won by Burt Rutan and Scaled Composites with Space Ship One is a good example of how well prizes can work.[10, 11]

With a prize, the donor does not have to try to predict in advance who can achieve the proposed goal

Except for one problem, of course: money. Winning prizes is usually only an option for people already rich enough to fund their own research. Prizes do not provide money when it is most needed—during the development process, so they do little for people with ideas but no money. True, you can look for investors, but you still have to convince them in advance that you can do the job. It’s no coincidence that so many entrepreneurs started out in marketing!

It’s also instructive to note some less-appealing details of the X-prize competition: once Space Ship One emerged as the clear leader, some competitors began to slack off, because there was no second place to strive for. Prizes fundamentally encourage competition and discourage cooperation, and they have all the benefits and dangers of competition as a result. In a field where effective cooperation seems to be essential to produce real quality, they can be seriously detrimental, as can be seen by the problems encountered by both Source Exchange and Co-Source—the two “reverse auction” funding sites Raymond mentions in “The Magic Cauldron”, which are now long dead.

Prizes fundamentally encourage competition and discourage cooperation, and they have all the benefits and dangers of competition as a result

Both were essentially “prize” systems. As such, these sites implicitly assumed that programs would be written by single entities (whether individual people or individual companies), since they made no provision for how prizes would be split among competing or cooperating interests. Therefore, they did not directly address the bazaar mode of development at all, and effectively discouraged it as a result.

If you have an idea that might be useful to a free-software project, and you expect to gain some benefit from it (such as using the resulting program), it makes sense to contribute your work. But what if you have a hope of getting paid for that contribution? It’s only natural to bargain for the best price for your work—so if there’s a cash prize to be won, you will withhold information until you can negotiate good terms for it. Now, all of a sudden, you, the well-meaning free-development contributor, are an “information hoarder”. Essentially, you’ve succumbed to the rules of proprietary development—even if the license of the released code will be free.

Both grants and prizes, therefore, introduce serious hazards for poisoning the self-selection and cooperative advantages of the bazaar development model. So, what else is there?

Narya Project

The ideas presented in this series are the motivations for my Narya project, which is attempting to implement a more effective incubator for free-licensed hardware development. I originally envisioned this as a small improvement over the Sourceforge site that I was using at the time. However, I quickly fell in over my head—the needs of such a system are complex, and I realized there were several pieces that ought to be separated out. Free development works best when independent reusable parts are separated, so as to increase the number of potential user-developers. Thats why I spun off the VarImage and BuildImage programs that I created in the process of writing Narya.

Narya presently consists of three larger projects: the original Narya Project Incubator and Forum [5] incorporates the basic CMS + forum concept, Bazaar [6] is the e-commerce system, and LSpace [7] is to be an archive and cataloging system. It seems very likely that a fourth major component will need to be a collaborative CAD system. Narya is based on a Zope[24]/Python[25] web-application platform which pretty much takes care of the CMS infrastructure. I'm still working with Zope 2, but it seems likely that moving to Zope 3[26] will be a big help.

The customer is always right

At this point we have to look at things from the point of view of rational potential donors—something which has seen surprisingly little thought. After all, the donor—the person who pays money into the system hoping to reap some benefit from it—is the customer. And the first rule of staying in business is to serve the customer.

Why would you want to fund a free-licensed hardware development project? Surely the most likely reason is that you have a need for the technology which is to be developed. If you’re willing to buy products at a certain price to remunerate a company for making them for you, shouldn’t you be equally willing to pay money in exchange for the invention of a new technology or method which you can use to your own advantage? The latter is worth far more than the former, so why is this hard?

The first rule of staying in business is to _serve the customer_

The problem lies with the things that the would-be donor fears will go wrong, and therefore with the assurances that they want from any system they’ll be willing to contribute to. These can be used to determine what sort of features our donation system must support:

Free Riders

- Fears: They will bear full burden of research rather than a marginal amount.

- Wants: Assurance they will be joined by other donors to support the research and won't lose their money on a failed venture because of underfunding.

The Rational Street Performer Protocol (RSPP)[12], solves this problem by encoding “rational pledges” based on a combination of base donation, matching funds, and spending caps, which more accurately models donor desires.

Fraud

- Fears: Fraudulent developers or vendors will take the money and run.

- Wants: Security against violation of contract.

Escrow systems allow a disinterested and trusted third party to hold the money and verify that the claims on it satisfy all parties. This is a natural role for the site administration which handles all of the e-commerce transactions anyway, and can be automated.

Technical Incompetence

- Fears: Developers are not able to do what they propose.

- Wants: Some credentials on the developers and a good idea of how they hope to achieve what they are doing.

Developers and projects can be rated according to their past successes, particularly with financial processes. An automated system for tracking successful and failing bids and projects provides a way to do this without relying on peer evaluation systems (which suffer from under-participation). This is similar to how E-Bay determines good and bad risks for buyers and sellers[13]. Means can be provided for developers and projects to present other kinds of credentials through their web presence.

Financial Incompetence

- Fears: Project developers will be irresponsible with the money.

- Wants: To know what the money will be spent on, and assurance it is actually spent on what it was given for.

If the provision system is based on individual service contracts and not on an on-going fund, then each transaction is recorded automatically by the system. Since payments go direct from the donor to the vendor on the developers' behalf, there is no question of the developers losing or misappropriating the money. Thus a very high level of trust and accounting is maintained in an essentially self-service way by the donors themselves.

Logistical Incompetence

- Fears: Projects will be stalled by difficulties with sourcing, shipping and receiving, order correction and filling, or negotiating with suppliers and sub-contractors.

- Wants: Logistical problems to be dealt with by professionals, to keep the problem from dragging developers down.

The provisions system which provides escrow must determine whether orders are correctly filled. Processing contracts, bids, and supplies must be highly automated and low-maintenance for the developer, so as to create a high confidence level that they will succeed.

Wrong Goals

- Fears: That they do not know which specific projects would be the best to fund. They have general, vague goals, but are not aware (and unwilling to learn) the technical knowledge required to judge which means are best to achieve which ends. That funds will be overextended and disorganized.

- Wants: Leadership to determine where some or all of their contribution is spent.

Means must be provided for donors to communicate and organize themselves. Foundations or foundries are needed to foster particular broad areas of development and determine how best to spend donor money to maximize utility. Automated means for slaving a fraction of a donor's contributions to their chosen foundations should be provided (this is similar to how “mutual funds” are handled in investing).

In whatever system we invent for funding free development, we must remember to provide these features, if we want donors to contribute. The key thing to remember is that what we are doing with such a system is packaging and selling innovation itself directly to end-users who are willing to contribute to its creation.

What we are doing with such a system is packaging and selling _innovation itself_ directly to end-users who are willing to contribute to its creation

Keeping in mind the needs of the donors noted above, and the need to avoid poisoning projects’ development process, it seems the most effective method of introducing cash will be to directly provide for projects’ material needs. In other words, for the donors to have a means of supporting project purchases directly, through an auction and escrow system involving donors funding non-profit projects via the for-profit vendors who supply them. Using this method, we can grow a vendor supply marketplace to sustain the needs of free-design development. Implementing an effective solution as the Narya Bazaar will be the subject matter of upcoming papers—meanwhile, what can we do about the bazaar size?

A tavern, with really good napkins

How many brilliant mechanical or electronic designs started life scribbled on a napkin in a bar or coffee shop? This social aspect of the development process has not received nearly as much attention as it seems like it should—one of the main motivations for contributing to free-licensed projects must surely be the social reward of “hanging out” with like-minded people.

If we want to attract designers and developers other than programmers, who find glowing screens of text comfortable, we must provide a more comfortable online social millieu. In the virtual world, such socializing often takes place using web forum software like PHP BB[14] or “blog” software like Drupal[15] or Civicspace[16], which have proven particularly good at appealing to a wide range of people. So far, however, such systems have been very weak on “workflow” issues—the process by which content is collaboratively created, published, moderated, and archived to make it permanently useful. Most content on forum sites (as on mailing lists and newsgroups) simply drifts down into the bit bucket. Automatic archiving systems make a dent in this problem, but as they are indiscriminate, they wind up with little “signal to noise” in their archives. There are such collaborative ideas as oekaki [17], but these are nowhere near the sophistication that we need for online collaborative design.

How many brilliant mechanical or electronic designs started life scribbled on a napkin?

On the other hand, there are Content Management Systems (or CMS). They are very useful to companies (the typical electronic store is an example of a CMS, although they are used for many other purposes), so it should come as no surprise that a large amount of the development effort behind CMS design (proprietary or free) has come from corporate contributors. Unfortunately, the office milieu shows: most existing CMS packages create a generally dry and regimented environment, with fixed roles that smell of job descriptions and cubicles. That’s all fine for the office world, but that’s not where the innovation is!

What we need is the tavern-like environment of a forum or blog site, but with the all the technical tools of a CMS, so that the transition from idea-sharing to collaborative-development is as gentle as possible. We need to develop paradigms for allowing a CMS object to become the central focus of a conversation in a web forum context—as must happen in a design “mark up” or review process. For hardware design, we’ll also need engineering and scientific tools, which are not yet part of any free-licensed CMS system. So far, wiki software[18] seems to be the most promising in this area, although it needs improvement to work well with graphical information. These will also include better CAD and graphics programs (both 2D and 3D) as well as scientific analysis and presentation software.

Capturing the past, securing the future

Finally, as ideas evolve from inspiration to development and finally to history, we need to be able to efficiently archive and catalog the data so it can be found later. Hardware data in many fields is much longer-lived than in the computer software industry, so we should be prepared for information that needs to sit for decades without being lost.

The obvious experts on this subject are librarians, who have been fighting the battle of preserving information against the inevitable onslaught of entropy for all the centuries from the Library of Alexandria to the Library of Congress, against every peril from wars to bad weather. So, the Narya LSpace cataloging system will draw on the librarian-defined standard of the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) [19, 20].

Every single technology needed to go to the moon is in the public domain

This is not merely a future concern—even now there are many thousands of free-licensed hardware documents which might form a seed, from which later development could grow. The United States government alone funds billions of dollars of research every year, and has been doing so for decades. Much of it goes immediately into the public domain upon publication in “government deposit libraries”. Even when it doesn’t, patents have a limited life, so what they did before 1985 is certainly public domain now. Among other things, this means that every single technology needed to go to the moon is in the public domain.

Imaging, converting, archiving and cataloging all of those documents will be a substantial project in itself. Of course, if we are successful, such capturing of past data will gradually defer to output from project incubators, so another important design element is the archiving tools which allow project or topic data to be compressed, bundled, and shelved into the virtual library database.

Working the magic

Probably, had there never been a free software movement, the idea would never have come to try free hardware development. Our conventional methods are based on exploiting the intrinsic market friction of the manufacturing process, and it is largely due to misapplication of this experience that the free software movement itself encountered so much resistance. Nevertheless, the free software movement has defined a large territory of development space in which the free model is vastly superior in innovation and quality.

Probably, had there never been a free software movement, the idea would never have come to try free hardware development

With that holy grail to inspire us, the goal of making hardware development acquire the same properties, seems worth the considerable effort. But if we are to “work the magic” in the hardware realm, we have to find the right kind of lubrication to eliminate market friction. We will never reach zero friction, but even software is not truly “friction free”, so we do have some margin to work with. The questions are simply “How little friction is little enough to maintain the ‘friction-free’ illusion?” and “How do we reduce the friction to that point?”.

In the second and third parts of this series, I will address those questions in detail, but it is clear that there are techniques that we can use—developed already for other areas of e-commerce and network communications and collaboration. It is even true that some forays into free matter economics have already been ventured, and that there remains much room for improvement. The road is rocky, but there is a road!

Bibliography

[1] R. Buckminster Fuller, in Critical PathFAQ

[2] Richard M. Stallman, The Gnu Manifesto

[3] Eric Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar

[4] Eric Raymond, The Magic Cauldron

8(http://www.lart.tudelft.nl/)

[9] Open Hardware General Public License (orignally from Open Cores, but removed), copy

10(http://www.scaled.com/projects/tierone/)

11(http://www.xprizefoundation.com/)

[12] Paul Harrison, The Rational Street Performer Protocol

[13] E-Bay policies

16(http://civicspacelabs.org/)

17(http://www.oekakicentral.com/)

[19] IFLA, Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records

[20] Morbus Iff, LibDB

[21] Robert Zubrin, Mars Direct

26(http://www.zope.org/DevHome/Wikis/DevSite/Projects/ComponentArchitecture/FrontPage)