Of course, the construction of a free road does cost money, which the public must somehow pay. However, this does not imply the inevitability of toll booths. We who must in either case pay will get more value for our money by buying a free road.—Richard Stallman

Past economic models relied much less on proprietary manufacturing and consumer product sales, with more emphasis on manufacturing and repair as services called on by users who considered self-repair and self-manufacture as defaults. Despite modern concerns to the contrary, this approach is not destructive to a commercial free market. If anything, such an economy represents a more ideal capitalist marketplace. The creation of a substantial free-licensed development bazaar will provide an environment in which companies catering to these needs can thrive and become much more competitive with the corporate consumer product manufacturers which presently dominate our economics. Clearly this is a necessary shift if we are to obtain the flexibility and self-sufficiency needed for developing the new frontier in space.

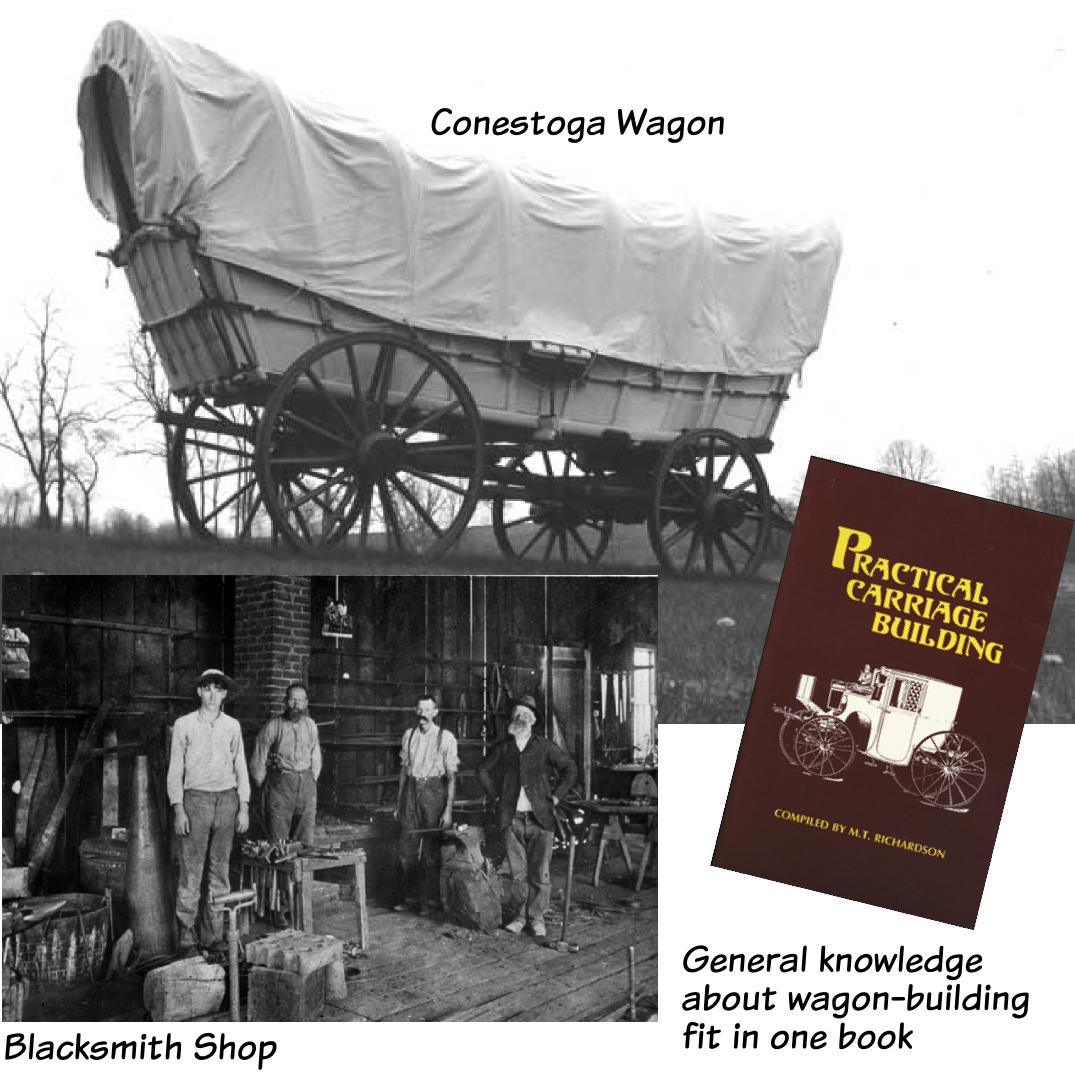

As we consider the needs of new pioneers, it makes sense to draw on the experiences of old ones. During the westward migration of the nineteenth century, American settlers travelled mainly by “covered wagon”—a rugged cart made of wood, with some iron or steel parts, and a canvas covering to protect the occupants, drawn by oxen or horses. There were no “brands” of covered wagons, although there were several common types and sizes. Nor were wagons produced in factories. Instead, they were usually made by the settlers themselves, with the help of manufacturing services from local blacksmith shops. Repairs were handled in the same fashion[1].

As we consider the needs of new pioneers, it makes sense to draw on the experiences of old ones

A wagon is transparently reverse-engineerable, there is very little of its mechanism that is either invisible or non-obvious in its function, at least once you’ve seen it work. So naturally, anyone with some mechanical skill could make parts or whole wagons on their own. Patents were much harder to get back then, and in any case, the construction of a wagon was well-understood and therefore unpatentable. Even if a particular component was patented, this was easy to avoid, since with so few parts, there were relatively few interfaces to constrain designs and alternate methods could be used to do the same job.

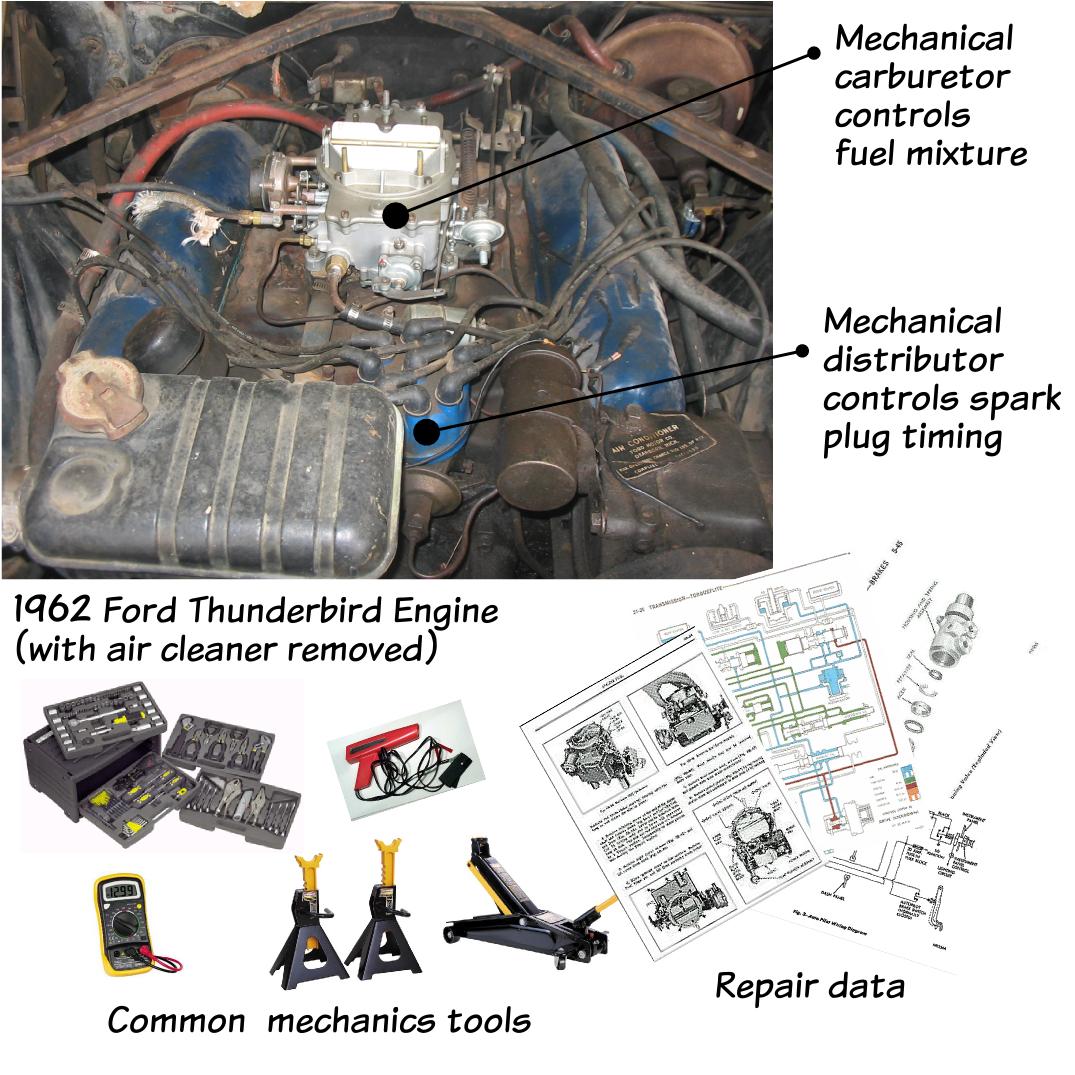

Even as late as the 1950s, when the automobile had long since replaced any form of horse-drawn vehicle, and corporations had taken over the manufacturing role, Americans took pride in learning to repair and customize their own cars. For about four generations, America was graced with a new class of skilled amateurs known as “shade tree mechanics”.

To a skilled amateur or professional mechanic, the important aspects of an engine could be easily figured out by disassembling it

Engines of that era were still almost exclusively mechanical devices. You could get repair manuals, which were useful, but to a skilled amateur or professional mechanic, the important aspects of an engine could be easily figured out by disassembling it. Some engine parts were patented, of course, but not as many as you might think. Any patents on the original internal combustion engine design had of course slipped into the public domain by 1950, and high standards for originality were still in place in the patent office, so the market remained very free. It was then, and is still, fairly easy to buy third-party replica parts for these engines. Failing that, most of them could be made in a small machine shop of the type that can be found in towns all over America. The increased complexity of the automobile engine was ameliorated by the rise in standardized fasteners and tooling standards optimized for ease of repair with the small toolkits that were (and still are) widely available[2].

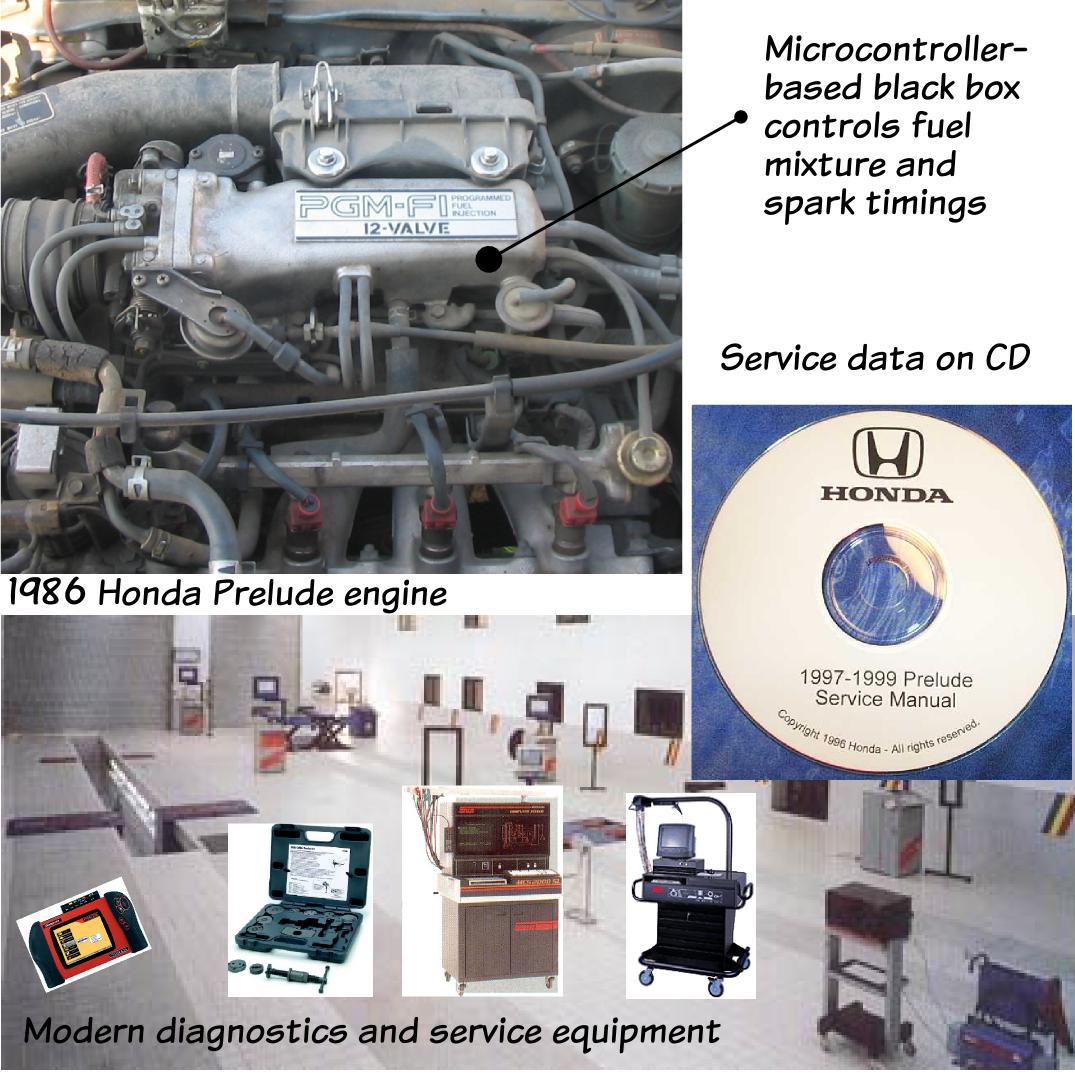

Then came the 1970s, with rising fuel prices, concerns about vehicle emissions (and the resulting regulations), and the availability of sophisticated digital electronics. The need for increased efficiency drove manufacturers to use integrated microcontrollers and other “black box” devices in their engine designs, primarily to improve combustion efficiency. At the same time, the American culture was seeing a boom in consumer culture, and new urban values of comfort and convenience began to supplant the old frontier ideals of self-sufficiency and independence. Car owners were going to professional mechanics instead of trying to fix cars themselves, so they no longer cared how difficult the cars were to work on. Manufacturers replaced simple standardized components in their designs with ones that were more convenient to put on in the factory, trading future repairability for lowered factory expenses. Planned obsolescence was introduced, with fixed engineering lifetimes on cars. Hoping to cash in on the public’s desire for novelty, car designs changed rapidly with many proprietary customized parts for the shell of the car. For professional auto shops, these changes were relatively benign since the costs of new and more expensive diagnostic and repair tools could be distributed over many customers.

The need for increased efficiency drove manufacturers to use integrated microcontrollers and other “black box” devices in their engine designs

For the shade tree mechanic, however, these cars are a nightmare. They have many critical parts which cannot be reverse-engineered to work. Instead, manufacturers print “repair manuals” which are high-priced, protecting professionals at the expense of the amateurs who can no longer afford the cost of the intellectual property required to fully understand and repair their own personal vehicles. Many specialized tools are needed, instead of the customary standard set of wrenches and screwdrivers. Globalized manufacturing results in cars with both metric and US units, requiring the mechanic to carry both types of tools. Disposable connectors, not widely available to end-users are used so that assemblies are not always reversibly connected. Worst of all, the “black box” microcontrollers cannot be serviced without specialized interface computers and terminals, generally only available to authorized repair shops[3]. In the end, the tooling required to fully maintenance a modern automobile costs more than the car itself!

In the end, the tooling required to fully maintenance a modern automobile _costs more than the car itself!_

Throughout this process, the end-user has been disenfranchised by the centralization of this kind of technocratic power. The essential result is exactly that of closing the source code to the automobile. This trend has continued right up to the present day, and the shade tree mechanic tradition—and the self-sufficiency ideal it represents—is dying because of it. This is extremely bad for those who want to see a new era of pioneering and self-sufficiency on the space frontier. Clearly, a reversal of this trend is needed.

Repair cultures and manufacturing services

There are still cars with healthy repair cultures. The Volkswagen Beetle is perhaps the most pervasive of these. Based on a simple design, preserved almost unchanged for the many years the car was in production, the Beetle is an easy target for salvage and repair. It’s easy to find parts that will match without worrying about so many “designer changes” between year-models (it uses “standard formats”), and there are many replica parts made by third party auto parts manufacturers[4].

The Beetle remains cost-effective largely because of market-forces arising from this mix of advantages which it shares with free-licensed open-source technology

Without spurious patents, the parts can be manufactured with few legal concerns (“free licensed” design is used), and since the Beetle’s engine dates from the era of mechanically-tuned engines, it is relatively straightforward to reverse engineer by simple inspection (it uses implicitly “open source” hardware).

The Beetle remains cost-effective largely because of market-forces arising from this mix of advantages which it shares with free-licensed open-source technology. It suffers, of course, from being environmentally unsound, which is why the Beetle has not been manufactured in the United States for decades. The design has not been modernized, and the so-called “New Beetle” is based on a completely unrelated chassis and engine[5].

Naturally, of course, the Beetle would not be the most profitable vehicle to manufacture, since users can keep them running for so long by self-repairing them. So, is the strong repair culture model of production and maintenance “anti-capitalist”? Hardly! It merely promotes a different sector of businesses, including repair shops, how-to magazines and manuals, and after-market parts dealers. Manufacturers, machine shops, and customizers have all made the Beetle repair culture into a big commercial success for many businesses all over the world.

Furthermore, there are many societal advantages to this model. Unlike the disposable culture, the repair culture does not fill up junkyards with useless carcasses reclaimable only by recycling to component metals, and smaller service-oriented businesses are favored over multi-national conglomerates. This makes for a healthier capitalist marketplace, less pollution, greater distribution of wealth, and greater service to the end-user. This is the sort of capitalist marketplace that Adam Smith had in mind, not the world of corporate oligopolies and planned obsolescence that closed source design and overuse of patents has led us to[6].

The advantages of the Beetle were arrived at by accident more than design

Promoting small, localized business is also a defense for small business owners and their employees alike from the market globalization that has led to the bleed-out of manufacturing businesses from wealthier nations to the developing world: by reinventing themselves around a service model and operating closer to their target markets, they can remain competitive by focusing on the strengths of local businesses—improved service and a closer understanding of the customer.

The advantages of the Beetle were arrived at by accident more than design: there was no formal decision to free-license the Beetle, it simply arrived at this state through inexpensive design not relying on patented technologies and the passage of time, allowing patents to expire. This leaves modern automotive users with the option of a freely-repairable, but outmoded and polluting vehicle, or a modern vehicle which they are effectively disallowed from repairing.

Free-licensed open-source software provides an example of the means by which this kind of commercial success can be achieved by design: we could build hardware using open-sourced designs from the outset

Free-licensed open-source software provides an example of the means by which this kind of commercial success can be achieved by design: we could build hardware using open-sourced designs from the outset. For companies hoping to profit from the repair culture, this could be a great boon, but it leaves us with the problem of organizing and funding the development process, since such companies are small and distributed, whereas design and manufacturing of hardware technologies as complex as the automobile have hitherto required the use of resources only large centralized organizations have been able to marshal. Unfortunately, those organizations, who generally rely on profit from sales to recoup the costs of development, are unlikely to embrace the free-design model. Must small business manufacturers alter their plans to suit this corporate agenda, or is there an alternative form of organization that can accomplish the same goals in a way that better suits both customer and vendor?

Deconstructing the corporation

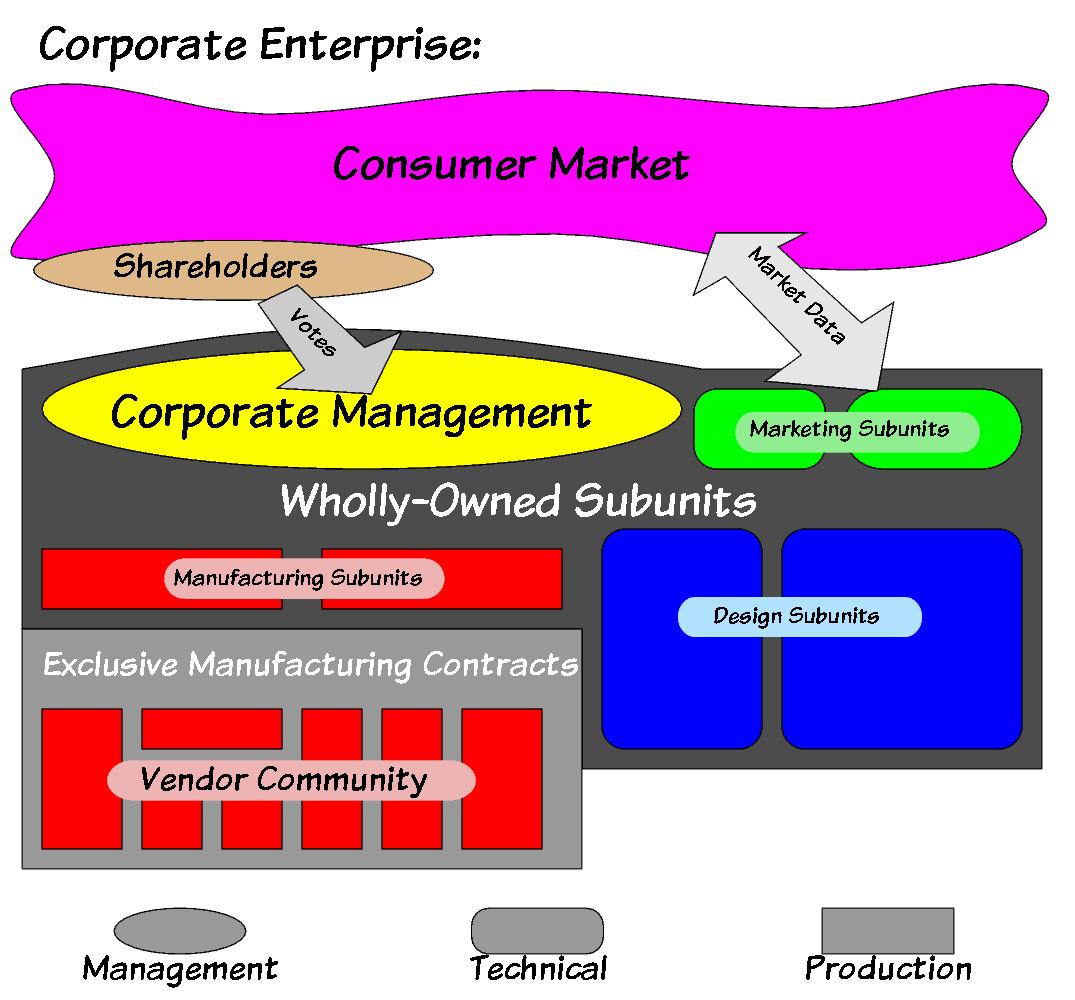

When considered as a social order rather than as an individual institution, a large corporation approximates a centrally planned economy with all of its flaws. Despite the great expense of traditional management, decisions have historically tracked only loosely with the needs of customers, resulting in enormous gaps between consumer expectations and corporate performance—exactly the properties that killed most centrally planned state economies in the 20th century. Only the absence of a viable alternative structure would seem to explain the continued success of corporations.

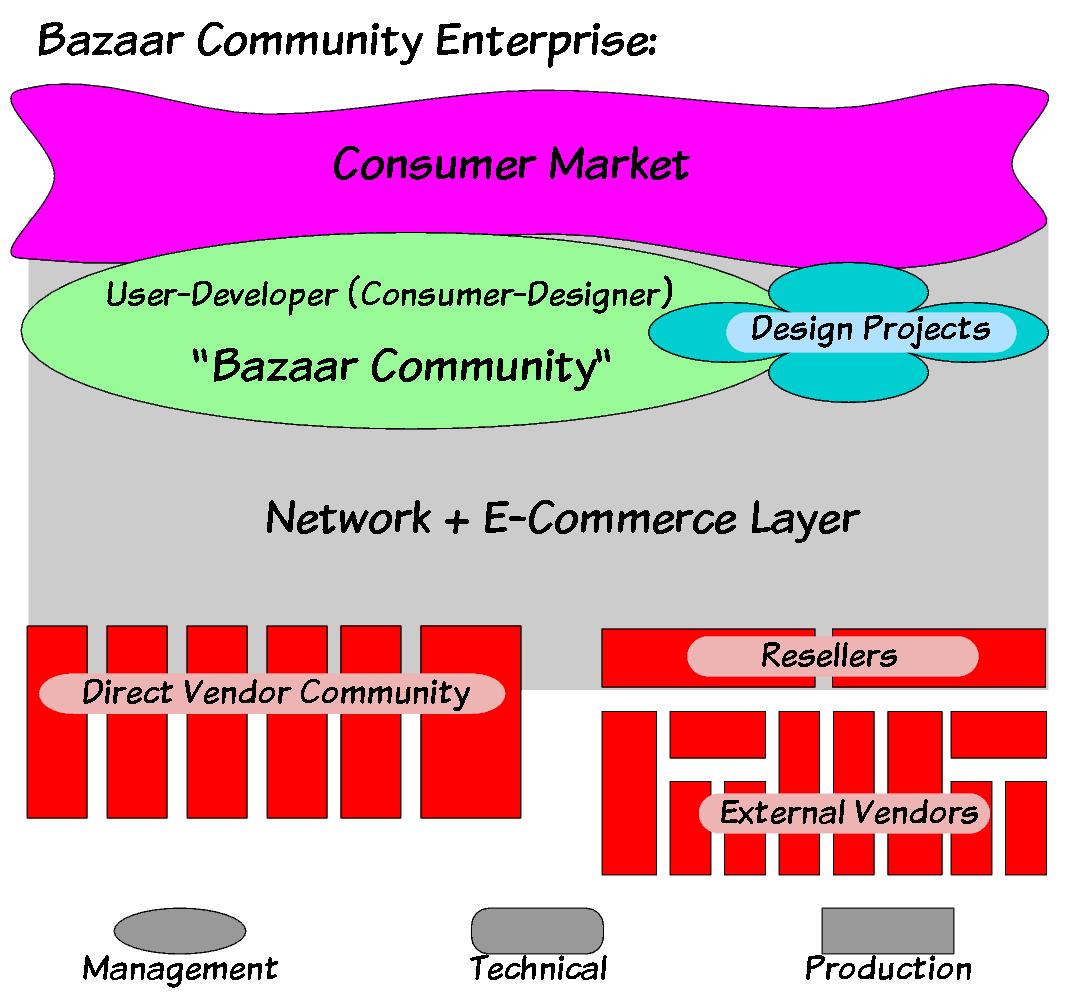

From the same perspective though, a community-based enterprise, consisting of self-organizing free agents is a free market, with all of the resulting advantages of accurately and naturally tracking participants’ needs and wants and requiring far less overhead to maintain. In a bazaar development community, customers are directly involved in the innovation process, and thus customer needs are freely translated into designs. All manufacturing is then “outsourced” directly to the same small manufacturers who would previously have contracted from the corporations. In this way, the free bazaar replaces the proprietary cathedral of the corporate design center.

The remaining utility of the corporate structure as a medium of exchange of information and trust between subunits can be replaced by a thin, automated network layer

When all of the manufacturing capacity has been outsourced to small vendors and the design process is under the direct control of the customers, what value is left in the corporate management structure? Management decisions are then only an expensive, redundant, and error-prone noise-source which interferes with the signal of the bazaar’s free market of ideas and sucks resources out of the system. The sole remaining true utility of the corporate structure—as a medium of exchange of information and trust between subunits—is a routine, deterministic process which can be replaced much more efficiently, accurately, and cost-effectively by a thin, automated network layer.

With the baggage of the actual manufacturing process removed, the products of the design center become information products, freeing design centers to use free-licensed methodology, leaving only the problem of implementing effective software tools for managing the distributed design process and maintaining the bazaar community[7]. Obstacles to contracting the manufacturing service directly from the end customer are merely technical: how to mediate the exchange of resources required and resolve trust faults in the process[8].

Surviving ephemeralization

The factory has become increasingly like the printing press, and the printing press has become increasingly like the computer printer: manufacturing is trending slowly towards the ideal of a Star Trek “replicator” which can make anything given sufficient energy and a blueprint. Even the modest progress achieved in this direction in the form of “3D Printers” and other highly-flexible rapid-prototyping machines is likely to have a significant impact on engineering and manufacturing industries.[9]

The factory has become increasingly like the printing press, and the printing press has become increasingly like the computer printer

While that may seem like a perfect situation for the consumer, it threatens change for the manufacturing industry. For the foreseeable future, the existing trends in manufacturing, towards reduction of both the marginal and capital costs of production will mean that, increasingly, the capital cost of a product is not in the capital equipment required to manufacture it, but in the effort required to design it. For the design centers, this suggests the viability of applying free software methods.

For small manufacturers, this could be an opportunity to contract directly for the production of freely-designed hardware to the end customers and the developers who designed it, cutting out the intermediary of the large corporate contractor, and putting the smaller business into a position of much greater freedom. Without non-disclosure or exclusivity agreements, patent licenses, and tightly binding contracts to worry about, the small manufacturer has much less buy-in and therefore less risk with producing free-licensed hardware. Likewise, the greater availability, greater flexibility, and lower cost of capital manufacturing equipment will mean that the manufacturer can become sufficiently agile to meet the short-run and prototype manufacturing needs of a bazaar-style community, in much the same way as the publishing industry has been able to adapt with print-on-demand and short-run publications for the rapidly moving target of the free software community.

Without non-disclosure or exclusivity agreements, patent licenses, and tightly binding contracts to worry about, the small manufacturer has less risk with producing free-licensed hardware

Large vendors organized around 20th-century-style mass production of consumer goods should increasingly see competition from these smaller, more agile vendors. Gradually, the disadvantages of centralized control will begin to outweigh the advantages of centralized production as the latter become weaker and weaker due to the manufacturing process approaching the replicator ideal.

Mitigating the risk-averse society

In the space community, as in many other fields of endeavor, many people bemoan the current “risk-averse” society in which it is almost illegal to take certain risks. More accurately, the legal code has moved to blaming manufacturers for injuries or other harm caused by use (or misuse) of their products. Such liability risks are among the most frequently cited reasons for small businesses not to make cutting-edge technology available.

Free-licensed design, however, offers two potential defenses against this kind of threat:

The first is “full disclosure”. Since the basis for manufacturer responsibility is arguably that the manufacturer is in a privileged information position, the complete disclosure of a product in the form of open-source design may be considered a fair way to transfer the risk onto an end-user willing to assume it.

The second defense is the “experimental” designation. It’s an indication that the full legal risk for the safety of the product must be assumed by the purchaser. It is routine for OEM companies rather than end-users to assume risk in this way, but if end-users purchase in the same way, the same rules should apply to them.

In the most serious case we can further remove the liability issue by collecting releases, using a nominal membership fee and a training process to make the “public” into “members” of an organization. This is how the Pacific Rocket Society (and presumably other similar groups) reduce their legal liability risk—only “members” are allowed at launches, and members sign releases assuming the risk[25].

Vendor niches

At present, the direct-sale market for small vendors is usually a narrow niche of hobbyists with relatively little money to spend and fairly modest requirements. But as a free-design community is encouraged to grow, increasing developer ambitions will create more and more opportunities for supply and service vendors who can support this development process and produce free-hardware products for end customers.

The existence of free-licensed design bazaars creates a new market for such companies whereby they can sell much more directly to the end customer

First generation vendors

Even in the beginning, hardware design bazaars will expand commercial opportunities for many vendors, including:

- Existing service manufacturing and repair businesses, such as machine shops, welding fabricators, and printed-circuit board printers who are already able to find customers, but could greatly expand their business by doing prototype work for free projects[10].

- Retail parts providers who currently specialize in the hobbyist market. The bazaar would provide opportunities for both direct sales and sales through resellers, allowing much more room for parts from smaller manufacturers[11].

- Tool and die manufacturers and retailers[12].

- Testing services which provide the primary means of establishing quality control in the manufacturing process (this is how manufactured product specifications can be verified).

- Professional consulting services, such as engineering design review. Although bazaar development primarily relies on user testing and user review of designs, there will remain significant demand for credentialed review of plans, especially as projects move from experimental to fully-integrated designs.

The existence of free-licensed design bazaars creates a new market for such companies whereby they can sell much more directly to the end customer, and remove their dependency on few large contracts; or from another point of view, the bazaar marketplace is a large customer, perhaps analogous to a government agency, but with far less red tape.

Later generation vendors

Once a free-design community becomes more established, there will arise niches for businesses which both supply and are supplied-by the community, manufacturing free-designs arising from the community, both for use in more complex designs and for direct sale to end-users. These end-users, just like the self-sufficient frontiersmen are really consumer-manufacturers, just like the user-developers that make up most of the free software user community. In the same way, they assume responsibility for the use of the design, which they have selected, paying only for the service of manufacturing—a very different bargain from that of existing consumer retailers. It is also possible, of course, for vendors to assume greater responsibility and market products through conventional distribution channels, incurring the resulting liability costs. This gives two additional vendor niches:

- Service manufacturing for the end customer (in the US at least, this sometimes requires the product to be a “kit” to be assembled by the end customer—one can buy “experimental” aircraft in this way)[13].

- Conventional sales of free-licensed consumer products. This involves increased liability and so will probably be more expensive, but can reach a larger market.

An eventual goal of free-hardware development, should be to create a full vertical range of free, commoditized and standardized components

An eventual goal of free-hardware development, should be to create a full vertical range of free, commoditized and standardized components, starting with things like LSI CPU chips[14] and concluding with entirely free-designed systems (like desktop computers, automobiles, or spacesuits). At the point that this is achieved, the products of the free-design community can begin to enter the mainstream of consumer products. Long before that, they will expand the alternative market for adventurous consumers who are willing to risk using experimental products.

Free patents or no patents?

As other writers have already argued effectively, the only thing patents are doing for innovation in the 21st century is drowning it in lawyers[26]. The reduced manufacturing friction of an ephemeralized hardware economy makes this drag force painfully visible. But what to do about it?

There are several proposed defenses against patents as a threat to innovation: One is to publish “prior art” for free-designs, so that they can’t be co-opted by monopolizers. Another is to define a “free-licensed patent” defending against patent restrictions just as the GPL does against copyright restrictions.

There is considerable disagreement, however, about whether such a patent license is possible[27]. Some previous attempts at this have been decidedly non-free, and unpopular with the free-licensed software community. It’s also possible to simply ignore patents—they are difficult and expensive to enforce, so it is likely that most never will be. Furthermore, in the US, ignorance of a patent is considered reason for clemency in cases of patent violation.

It is of course, possible to lobby for the elimination of patents, but this is unlikely to work until inventors can demonstrate the folly of patents by proving a viable alternative exists. Meanwhile, one of the techniques of living with patents will have to be used. In all probability, future innovation will resolve this issue, but until then, means such as the W3C Patents Policy[28] should be provided to allow both.

Vendor needs

This new marketplace will expand the opportunities for independent services and service-manufacturing vendors, but doing so requires recognition of the problems such companies will face in staying in business. The biggest problem is marketing. For a small auto machine shop “marketing” may currently mean only a sign, a well-chosen location near auto repair shops or a race track, and word-of-mouth advertising. For a one-off PC board fabricator, it may be little more than a website linked to hobbyist web pages (electronic “word-of-mouth” advertising)[10].

There are a number of practical problems with selling to customers through an online system, which vendors will naturally fear

The internet, of course, immediately suggests automated marketing opportunities, and just as E-Bay created a viable online marketplace for one-of-a-kind merchandise, putting the boutique business model online[15], there have been attempts to build online service brokering sites to advertise services, including manufacturing[16]. However, such sites are generally organized exclusively around service brokering, and so they are very supplier-oriented. This makes using them something of a chore to use—the sort of thing only a purchasing agent will do. Which leaves only the same customers that were available before the internet. This is no better than simply automating the Thomas Register, which Thomas has already done.[17]

There are, however, a number of practical problems with selling to customers through an online system, which vendors will naturally fear, and which therefore will need to be addressed in a system designed for contracting the manufacture of free-licensed components:

Non-payment

- Fears: Payment won’t be made even after the non-recoverable expense of manufacturing has been invested.

- Wants: Assurance that payment will be made.

This is what escrow payment is for, and why we need to have specifications that a third party can confirm.

Loss of control

- Fears: Agreements with brokering service will interfere with business’s independence.

- Wants: To pick and choose their own contracts.

This is why we must have an automated system for browsing specifications and finding suitable contracts, and why restrictions on basic vendor memberships must be kept minimal.

Too much overhead

- Fears: Any automated brokering system will take too much time to use, detracting from primary business.

- Wants: Either very easy, or someone else does it.

The automated system for browsing specifications should be easy enough for non-skilled users to take advantage of it (like a search engine). Finally, however, there is an opportunity for companies which resell the services of companies that don’t sell directly to the bazaar, such resellers will eventually come into competition with their suppliers as those suppliers learn of the site, providing for a gradual evolution from mostly reselling to mostly direct sales as the bazaar grows.

There is an opportunity for companies which resell the services of companies that don’t sell directly to the bazaar

No customers

- Fears: Site will be useless, no one will buy.

- Wants: Low risk of participation, site oriented to attract customers.

Existing service brokering sites are primarily for that purpose only, attracting only the most aggressive customers. The bazaar on the other hand, is primarily a design site for project developers and donors (who are the customers) to interact. Therefore the site will naturally bring vendors into contact with customers.

No scale economies

- Fears: Relying on short-run business will not be profitable enough.

- Wants: Ideally to batch products into larger runs for economy’s sake.

The promotion of standard designed components encourages projects to reuse already created components, for which tools and dies have already been made. The company which made the tooling investment will be in position to charge the least for future manufacturing.

Liability

- Fears: They will be sued by end-user customers for non-performance or even hazardous behavior of products.

- Wants: Indemnification of design responsibility: since vendors don’t design end-products they can’t be responsible for performance.

This is intrinsic to the idea of service manufacturing—the final integrator is the one responsible for performance. In the bazaar model, this is unusual because the final integrator is the customer. All sales must be on an experimental basis, and vendors should be able to limit sales to “responsible individuals” through such means as waivers and proof of age.

Patents

- Fears: They will be sued for patent-violation.

- Wants: Knowledge of patent infringement possibilities.

There is no way to absolutely remove this threat, as it is a problem endemic to the patent system, but the insistence on free-licensed designs and the free publication of those designs as prior art provide some assurance of design freedom.

The initial marketplace of the free-design community is contiguous with the existing hobbyist and do-it-yourselfer market

A free marketplace

The initial marketplace of the free-design community is contiguous with the existing hobbyist and do-it-yourselfer market. It is such technically-literate customers from whom free designs will be generated, and to whom most sales will be made, especially at the outset. The example of the shade tree mechanic stands as a cautionary tale of the dangers of proprietary and closed design, but it is important to realize that do-it-yourselfers are not gone. Despite their problems, the shade tree mechanics still persist, albeit mostly with older cars.

There are amateur machinists[18] and electronics hobbyists[19], model plane enthusiasts[20] and sport rocketry amateurs[21], aircraft homebuilders[22] and robotics competitors[23]. Altogether, amateur technologists are a powerful group. Even the reaches of outer space are not beyond them, as proven by over fifty amateur satellites launched, starting in 1961, all primarily created and maintained by radio amateurs. One of the most recent, AO-40, has even gone into high Earth orbit to return images of the Earth from space[24].

Complete self-contained, end-user-operated replication machines won’t arrive for a long time. However, we don’t need to wait for a literal "replicator" to see economic effects from such technology trends. Meanwhile, the falling costs of replication can be made less visible and more distributed. The acquisition of capital and coverage of marginal costs can be pushed further out—closer to the end-user or consumer, in the form of direct contracting to service manufacturing businesses. The cost of entry to design and manufacturing processes alike can be reduced, creating a system which empowers the end-user rather than centralized manufacturing centers.

Bibliography

1(http://www.endoftheoregontrail.org/wagons.html), construction, and blacksmithing

[2] From Sears, for example.

[3] But for serious amateurs, Software for Cars

5(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volkswagen_Beetle)

[6] Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776.

[9] 3D Printers: Solid freeform fabrication and Cubital's Soldier 5600

[10] For example, Pad2Pad

[11] For example, Mouser Electronics

[12] For example, Sherline Machine Tools

[13] For example, Kit-built planes

14(http://www.opencores.org/) and LART

[16] For example, Elance

18(http://sherline.com/resource.htm)

20(http://www.modelairplanenews.com/)

23(http://www.battlebots.com/) and Botball

[26] Faré Rideau, Patents Are An Economic Absurdity, and references therein.

[27] Links in All the Way Open

28(http://www.w3.org/Consortium/Patent-Policy-20040205/)

[29] M. T. Richardson, Practical Carriage Building, 1892.