If you had a matter economy based on free-licensed design, what would you do with it? Why does this apply to space settlements? Are there practical projects? Who would need them? Why is free-design the right way to go? This final installment in the free matter economy series will attempt to answer these questions by taking a brief tour of the kinds of roadblocks that lead to the concept of applying free software methods to space.

“[Astronaut] Anna Fisher got the job of helping design a [space]suit for women. This had nothing to do with fashion and everything to do with safety. A poor fit is unacceptable, because it would make it impossible to move. As a small person, Fisher found the unisex stock sizes simply unworkable. ‘Women are not smaller men’, she reminded the astronaut office, which apparently had to be reminded, ‘Women are built differently’. For a while NASA thought it would be more economical to select a large candidate who would fit the suit, rather than adjust the suit to fit a smaller woman, but tall women are also built differently, another lesson NASA had to learn.”—Bettyann Holtzmann Kevles, Almost Heaven: The Story of Women in Space [1]

Suppose that you do create a free-design community and a vendor economy to support it. What will you do with it? The idea covers many different aspects of life, but the part I’m interested in is the development of space. Why is it so essential to have a free-design bazaar to make space colonization work?

In part II of this series [2], I explored the importance of design freedom to the self-sufficiency that made past colonizations and migrations possible, following the example of the wagon trains in early 19th century America. The motivating necessity is the need for total field-repairability on the frontier. There’s not going to be a lot of warranty service calls to Mars!

Explorers and pioneers understand the importance of knowing their equipment, and in the extreme case of space settlement, there is no reasonable way to achieve this except through total disclosure of the design, means of testing, and engineering limits of the equipment used.

In fact, this is no more than NASA demanded of its contractors when it built the equipment to go to the Moon in the 1960s, so there should be no great shock in realizing that colonists will need the same power. But NASA represents a monopsony, a single-buyer market, where the buyer was deep-pocketed enough to pay those contractors everything they needed. Space settlers, especially if we are to imagine anything like a free frontier, will not be so top-down organized, nor so wealthy, and will have to manage their collective buying power differently.

Explorers and pioneers understand the importance of knowing their equipment, and in the extreme case of space settlement, there is no reasonable way to achieve this except through total disclosure of the design, means of testing, and engineering limits of the equipment used

There is also a very high premium on mass transportation for anything that must be launched from the Earth, so there will be a substantial demand for fashioning needed equipment from materials on site. Pioneers will have relatively little need to purchase equipment itself, focusing instead on the tools to begin the long bootstrapping process of building their own habitats and civilization out of little more than the dirt and sunlight they find in situ. Any economy that subsists from charging fees for centrally-manufactured copies of a secret or patented design is going to have problems with this model of living off of the land. This makes it difficult to rely on investment from terrestrial manufacturing industries which see little profit motive in serving the needs of colonists.

Personal technologies on the frontier

At the 2000 International Space Development Conference (ISDC) in Tucson, Arizona [3], I attended a small brainstorming session focused on what conference organizer and Tucson L5 member Tom Jaquish called “personal technologies for space” [4]. There were only half a dozen people in that meeting, but I was lucky enough to be one of them, and I still regard that meeting as a decision point. It became obvious to me that space pioneers need something that astronauts don’t: scaled down, personalized, fully-disclosed, and modifiable technology that is adapted for their fundamental needs of freedom and independence.

The independence is not entirely a matter of choice. Like the wagon train migrants of the 1830s, the space settlers of the 2030s will be far from physical help (though radio contact and the beginnings of an interplanetary internet will be available for most settlers [5]). That means that they will be forced, by necessity, to do much fabrication and maintenance on site, using the available materials. The space community officially calls this “In Situ Resource Utilization” (ISRU) [6], or informally, “living off of the land”.

It is the most fundamental part of Robert Zubrin’s Mars Direct concept [7], a basic tenant of the Mars Society which he founded, and at least an important part of the so-called NASA Reference Mission that he influenced. It is also fundamental to all realistic colonization and settlement plans, right back to the works of Gerard O’Neill, who first proposed mining the Moon to build giant space colonies at the Earth-Moon’s “L5” point [8]—incidentally motivating the creation of the L5 Society (one of the two space advocacy groups that merged to become the modern National Space Society).

This independence will require freedom and knowledge of precisely the kinds that are guaranteed by copyleft culture: settlers must be able to freely use technology, modify it to their needs, and share both their knowledge and their innovations with other settlers [9]. The frontier will require high levels of both cooperation and self-sufficiency.

This independence will require freedom and knowledge of precisely the kinds that are guaranteed by _copyleft culture_

This frontier-libertarian vision is at odds with corporate proprietary intellectual property culture. Settlers will be assuming their own risks, but in order to do so, they need total disclosure on the equipment they will be using—and that can only happen in an environment dominated by open standards and free-licensed, open-source hardware (and software).

With deep enough pockets, like Apollo-era NASA, you could simply bully the manufacturers into tending to your every whim. But this is not a very likely situation for independent colonists—they are much more likely to get shafted by corporate policies that are short-sighted here on Earth and potentially deadly in space. An omission in a manual, a microcontroller that can’t be reprogrammed, or a mechanism that can’t be repaired by a user could consign a colonist to death. If we let corporate suppliers run the show in space, it will only be a matter of time before the intellectual property system kills somebody.

The realization that this danger exists is not new. It has long been one of many reasons why those favoring a government-run program fear the commercialization of space by a new wave of corporate developers. There’s a real fear that “greedy capitalists” could fill the new frontier with modern analogs to the “robber barons” and “company towns” of the 1880s. Science fiction movies like Alien and Outland have explored this dystopic corporate future, and even Heinlein’s 1949 juvenile novel, Red Planet proposed the idea that Martian colonists would have to rebel against “absentee landlords” on Earth. However, the space movement has not been very forthcoming with ideas for how to combat this problem, especially if the large government agency is not the driving force behind it.

As for the practical utility of NASA in promoting colonization—forget it

As for the practical utility of NASA in promoting colonization—forget it. It isn’t NASA’s job, no matter how many NASA employees may be sympathetic to the cause. As a government agency, NASA can reasonably be expected to do research and development of space technologies and exploration of the space environment, but that’s it. The business of consolidating our hold on space, of developing it, of finding ways to become comfortable there, work there, live there, and raise families there—that’s something NASA won’t (and probably shouldn’t) touch.

Consider the terror that NASA has of civilians in space ever since the death of school teacher Christa McAulliffe in the Challenger accident [10]: more than 20 years later, NASA did essentially everything in its power to prevent space tourist Dennis Tito from going aboard the International Space Station [11]. The Russian RSC Energia/MirCorp partnership had originally promised Tito a berth on the newly privatized Mir space station, but due to pressure from NASA, which claimed the aging station was a “distraction”, Energia had scuttled Mir, dropping it into the Western Pacific over the objections of privately-funded MirCorp [12].

Sending Tito aboard the ISS was the company’s best solution for keeping its promise, and Tito, who paid more than US$20 million for the privilege, felt it was a fair deal. Tito made it to ISS because of Russian stonewalling and the realpolitik of ownership: they were launching him on Russian hardware to an ISS that at that time consisted almost entirely of Russian modules. It was a truly ironic moment in the development of space: the American socialist space agency objecting to the newly capitalist Russian space industry pursuing the profit motive with well-healed customers. Considering this history, who can believe NASA PR about space tourism, commercialization, and colonization of space is any more than lip service?

Contrasting these political realities and the thirty years of stagnation in opening the space frontier to real development by individuals with the sustained rapid pace of innovation in the free software community, I began to see that free hardware could be the answer to the decades of deadlock, sluggish progress, and ineffective lobbying that made up the space movement I had known all my life.

I began to see that free hardware could be the answer to the decades of deadlock, sluggish progress, and ineffective lobbying that made up the space movement I had known all my life

This series stems largely from that discussion in Tucson in the year 2000. Around the table we brainstormed about a series of necessary technologies that were not only necessary for space colonization, but with which colonists would have to be intimately familiar. Each one of these technologies would benefit substantially from free development methods.

Frontier spacesuits

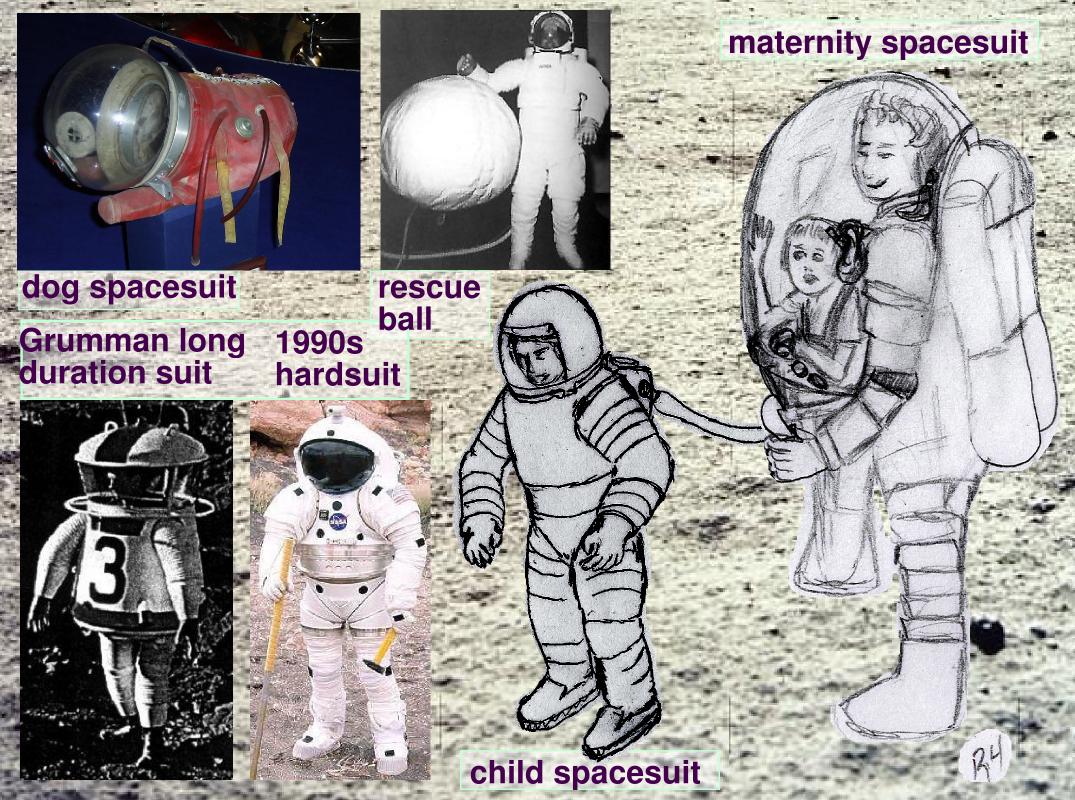

The number one most important technology is unquestionably the spacesuit [13]. On the frontier, everyone will need to have one. They may not get used all that much, since much of a space settler’s life is likely to be spent indoors (or “middoors” as Peter Koch likes to call it [14]), but for safety’s sake, and for the occasional times when it really will be necessary to take a walk, spacesuits are an unavoidable necessity.

They are also pretty complicated.

A spacesuit is an entire, wearable, self-contained life-support system, a human-shaped spacecraft. The suits used by the Apollo astronauts on the moon are a very good start, and there have been many new ideas incorporated into the suits used on the Space Shuttle. There are also Russian designs and private sources of hardware, including SCUBA gear.

Frontier suits will need to bear up under wear that was not required of NASA equipment

However, frontier suits will need to bear up under wear that was not required of NASA equipment. The moon suits were only used for about three days, and some experts don’t think they would’ve lasted much longer because of the incredibly abrasive effect of particles from the Lunar regolith. Moondust is created by micrometeroid “gardening” (accumulated breakage due to billions of years of impacts) and is therefore full of sharp edges, not having been dulled by wind and water processes that affect rocks on Earth (on the other hand, there is some rounding due to impact melting). It’s also quite hard. It is, in fact, very much like the “polishing grit” we use to grind glass.

Above all, suits for Moon or Mars will have to be built for field-repairability. It must be possible to replace a seal when the dust finally wears it out. If a helmet cracks due to a fall, it will be necessary to mold a replacement. Shipping replacement parts is likely to be prohibitively expensive.

Then there are children. When children reach a certain age, they will need suits, and their first suits will likely need to be children’s suits, designed to be easy for the parent to monitor, and hard for a child to mess up. Before they reach that age, it’ll be necessary to decide whether very young children should be in unarticulated containers like the “rescue balls” that were designed early in the Space Shuttle program 15, or whether it will make more sense for them to be inside a parent’s suit—which implies the engineering problem of designing a maternity spacesuit, specifically for pregnant and nursing mothers.

When children reach a certain age, they will need suits, and their first suits will likely need to be children’s suits, designed to be easy for the parent to monitor, and hard for a child to mess up

“Settlement” by definition includes children. Will budget sensitive national organizations overcome their fear of a public relations incident to send families with children into space? Will they then develop the necessary hardware to do so? It seems to me that the only way such important technologies will be developed is by the direct participation, through a free design bazaar, of the people who need them.

Biospherics and space agriculture

Space settlers will, in the main, be farmers.

This seems to be a startling idea to a lot of space advocates and government-sponsored space developers I have encountered. The idea is that (somehow) space colonies will go straight to an industrial, urban culture supporting highly-specialized professionals like scientists and engineers. There is apparently some desire to (somehow) skip over the “dirty” business of developing an agrarian base for the new civilizations in space.

Every human civilization in history has started by establishing an agrarian base, and extra-terrestrial settlements aren’t going to be any different

Sorry, but it can’t be done! Every human civilization in history has started by establishing an agrarian base, and extra-terrestrial settlements aren’t going to be any different. People have to eat. That’s the only path to self-sufficiency, and “cheap access to space” (CATS) notwithstanding, space travel just isn’t going to be cheap enough to support it as an outgrowth of the terrestrial economy. Space is another country with its own—separate—economy. As a matter of “national” necessity, then, it will have to have its own independent agricultural support system.

At the same time, we have to recognize that “farmers in the sky” cannot possibly use the same techniques that we have used for centuries here on Earth, and there are no “natives” [17] to teach us the new cultivation techniques. Instead, we will have to rely on experts—engineers and scientists—to develop our initial guesses, and we will have to play conservatively, while the first wave of pioneers learns “how things really work”. There is no one yet alive who has the right kind of “common sense” to be a good space farmer—we have to find, train, and cultivate those people.

We will have to rely on experts—engineers and scientists—to develop our initial guesses, and we will have to play conservatively, while the first wave of pioneers learns “how things really work”

This means that one of our first tasks is to scientifically attack the problem of how biospheres in general, and space agriculture in particular, can be managed. So far, this is a much ignored (and occasionally maligned) enterprise.

The best research to date is that of Biosphere 2 [18], but it was plagued by bad business decisions, starting with the idea of running the project as a for-profit enterprise which created a strong conflict of interest, motivating academic dishonesty. We know for a fact that some important figures were “fudged” in order to make the operation seem more “viable” from a commercial perspective. The result was endangerment of the experimental subjects and corporate in-fighting that resulted in the shutdown of the project [19].

Biosphere 2 failed as a project and Space Biosphere Ventures as a company. The campus was transferred as a research institution to university management, which gutted the original project, repurposing the facility to more fashionable Earth-centered environmental research. In only a few short years, however, that program also collapsed. In early 2006, the Biosphere 2 campus was purchased by a tract homebuilder. Perhaps they will preserve it as a park, or perhaps they will mow it down to build condominiums. Either way, it will no longer be contributing to the necessary knowledge of space habitat biospherics, and there is no replacement in design or construction as of this writing—one more example of “big science” waste due to cancelling a concept that was in principle, the right thing to do, but was destroyed by bad management, lack of funds, and politics.

In early 2006, the _Biosphere 2_ campus was purchased by a tract homebuilder

The problem here was the conflict of interest. Even if the project is run by motivated, good-intentioned individuals, the need to turn a profit in the process of conducting research creates too much pressure to fake “success”. The greatest irony is that had Space Biosphere Ventures been completely honest, it would have contributed useful research, despite the problems. The problem was that “useful research” wasn’t enough. They needed a blockbuster hit in order to keep drawing in the paying tourists and the investment that they relied on to continue the research.

Simulated dirt and space construction methods

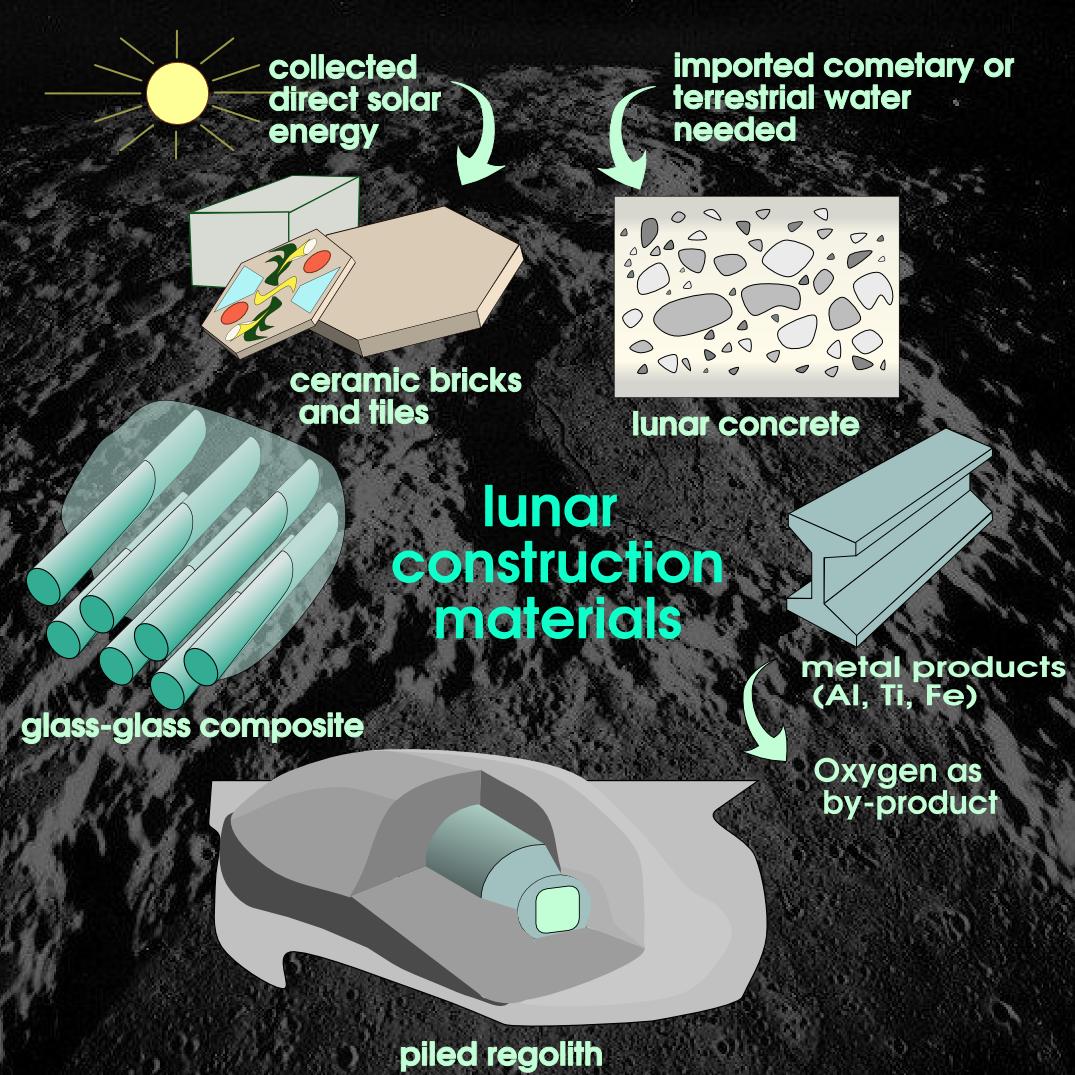

Like the settlers on the Great Plains who built houses out of the only available material—sod—settlers in space will need to learn how to build out of what they can find. For most, that will be something like Lunar regolith—a dusty, mostly-silica volcanic soil which is the result of igneous rock dating back to the formation of the solar system and the period of the “great bombardment”, pulverized by the long history of later micrometeroid impacts (called “micrometeroid gardening”).

Soil like this is pretty hard to find on Earth, but there are some people who make substitutes that are acceptable for many purposes. We need to learn how to use this material to build adequate shelters in space [20].

Like the settlers on the Great Plains, settlers in space will need to learn how to build out of what they can find

There are various approaches to this, including:

- Process the material to extract metals and build metallic structures [21]

- Add water and make “lunar concrete” (although on Luna, water is an import good!) [22]

- Make glass fibers and add amorphous glass to make “glass-glass composite” [23]

- Bake it to make ceramic bricks [24]

- Push it around with soil-moving equipment to make “earthen structures” [25]

Each of these implies a whole series of “civil engineering” challenges which settlers need to see solved. How will this be done by corporate developers? Where’s the profit? It has little or no sale value, even though it has enormous use value to the settlers who need it.

Fields of power

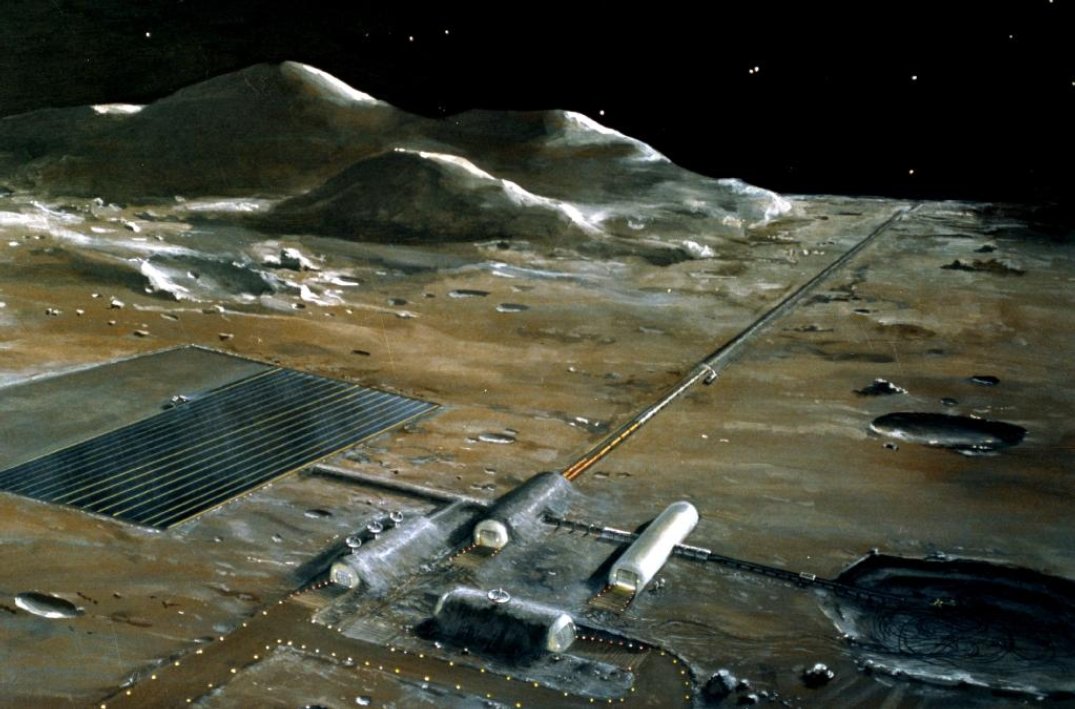

There are different approaches to power needs. Some people think that nuclear reactors, burning lunar-mined thorium are likely to be important [26], but the most common proposal is to use solar panels. Lots and lots of solar panels.

Terrestrial farmers rely on the process of photosynthesis to collect free energy from the Sun, which drives their whole system. Photosynthesis as such is likely to be internalized in many space colonies, since natural sunlight will often be inadequate for one reason or another (wrong length of day or too far from the Sun, for example), so that plants will be mostly cultivated under high-efficiency growlights. But what’s powering the growlights?

In contrast to the internal biosphere of a space colony, its external ecosystem is an open system. The colony, considered as a whole is a space-adapted life form which consumes sunlight and regolith and emits (at minimum) slag and heat. In order to collect energy, it will need to use some of the collected mineral material (mostly silica) to produce photovoltaic cells to be used in fields of solar panels [27], which will sustain the energy needs both for agriculture and for the industrial processes that lead to collecting more regolith to manufacture from.

From the outside, a space colony can be thought of as a space-adapted lifeform that consumes sunlight and regolith and emits slag and heat

This too requires development of technological processes—we don’t yet have a formula for exactly how you go about converting regolith into solar panels. Nor any of the other complex systems that will form the backbone of a space colony. Here also, it’s difficult to define a saleable product with enough market potential to justify the research from a conventional capitalist manufacturing perspective.

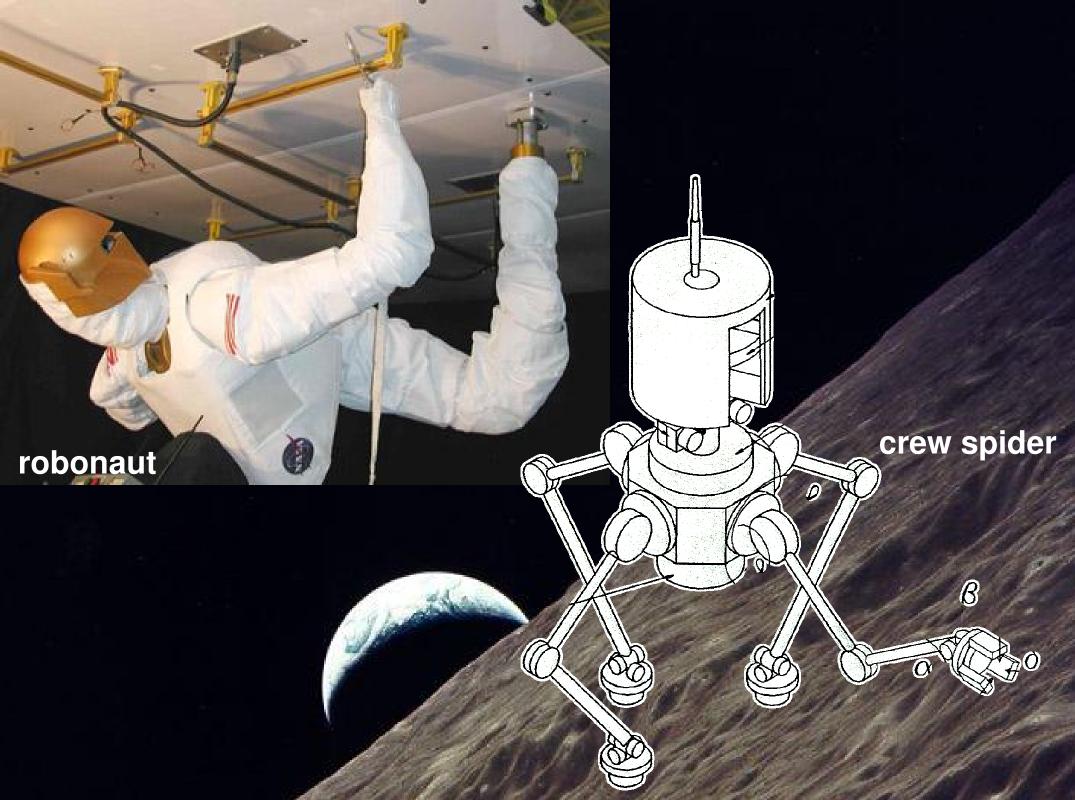

The labor limit and robotics

People like to talk about a “work-ethic” and there is a certain fear of robots “taking over” jobs from Humans, here on Earth, which seems (and is) silly, except for the byzantine complexity and luddite sluggishness of the Terran economy. NASA, due to vagueries of the federal funding it receives, is so often forced to justify the use of humans in space that it has developed a vested interest in proving the inadequacy of robotics. There is a very real fear that a too-capable robot will threaten the funding base for manned spaceflight.

For space pioneers, however, what was a luxury becomes a necessity: there is a fundamental limit to how much labor a habitat can take to operate. An artificial biosphere must, at absolute minimum, require fewer people to run than it sustains.

If it doesn’t, of course, then the biosphere is doomed to run down, and given the size of such systems, it will do so quickly. On the other hand, even if the system manages this minimal limit, it will still not be adequate, because Humans cannot work 100% of the day or of their lives. A short-term outpost can operate close to this limit, under emergency conditions, with solely able-bodied crew to maintain it, but that is a poor description of a real settlement.

Real settlements are towns with families. They have people both too young and too old to work, and people whose work is taking care of that fraction of the society. They have people of varying skills. Even “able bodied” people must have some tolerance for “down time”, whether due to disease or depression. The actual labor output of a naturally-distributed Human population is probably no more than 10% of the hypothetical limit of a group of hypothetical “able-bodied” people hypothetically working full time.

_An artificial biosphere must, at absolute minimum, require fewer people to run than it sustains._

That means that the maintenance labor of a biosphere must be less than 10% of the theoretical labor limit for the number of people it supports. Occasionally, an emergency (or a harvest) may exceed this limit, but such emergencies must be relatively rare and recovery time must be figured into the design. This is true of terrestrial farming, of course—it’s true that the work load during plantings and harvests is huge, and there is always maintenance to be done, but there’s also a lot of time “watching the corn grow”. On Earth, farmers rely a lot on natural, self-regulating systems, but space agriculture always involves relatively high-maintenance artificial growing environments. It’s necessary to design and build the self-regulation into these systems to make them workable.

All of this means a massive investment in automation and computerized management of biosphere and space agriculture systems. Only free-designed open architectures, adaptable to each colony, maintained and developed by users of such systems, can hope to provide the levels of flexibility, reliability, and low maintenance that this task requires. Corporate lock-in to particular suppliers has no place in this complex system.

Interfaces: where my nose ends

There is an expression of libertarian philosophy that says, “Your freedom should end where my nose begins”. The essence of this philosophy is the ideal of a “maximally and equally free” society: freedoms are curtailed when they curtail other peoples’ freedoms. Ultimately, it’s a statement about interfaces: when does the freedom of one individual start to restrict the freedoms of another? It’s clear that there is no absolutely objective definition of this point, just as there is no such thing as perfect freedom. Nor do advocates of freedom advocate irresponsibility—generally the reverse is true. In a highly technological world, this problem often resolves to understanding and respecting standardized interfaces and formats.

Today, we live in a world where most technology interfaces with other technology—often through very arcane and sometimes deeply secreted interface standards “published” only to those that the original technology rights holder authorizes

In the era of the covered wagons or even of the great sailing ships of the 19th century, most technology interfaced only with the natural environment, or, at worst, could be easily adapted using handtools and ordinary craftsmen’s understanding of the basic principles (it was de facto open source [TFME2]). Today, we live in a world where most technology interfaces with other technology—often through very arcane and sometimes deeply secreted interface standards “published” only to those that the original technology rights holder authorizes. This puts the end user far more at the mercy of the original equipment manufacturers than they have ever been—their freedom is restricted by it.

For the end user, this is the point of opening the source to hardware designs and documentation [32]—it is essential for the interfaces to be free for the use of integrators, other manufacturers, or the end users, or we are destined to drown in a sea of red tape, bringing many areas of technological progress to an artificially-imposed standstill. Space exploration and development is just one of many such areas, but it may well be the hardest hit, because nearly every piece of technology needed has been affected by the 20th century clamp-down on technology, the centralization of manufacturing and engineering power under corporate control, the mass fear and subsequent disallowance of individuals using advanced technology, and the paranoia of the Cold War or of terrorism.

In order to escape from this technological entrapment, and build a free future, we will have to accumulate a new body of standards for technological interfaces, either by encouraging the existing holders to free them, so that they can participate in the free economy, or by establishing new, free, standards, and encouraging their adoption in hardware by promoting the advantages of such free standards.

By the people, for the people

The Crown of Spain paid for Columbus’ voyage of discovery on which he found America, but the Crown of England did not pay for the Mayflower which was sent to settle there; Lewis and Clark explored the Northwest of America looking for a “northwest passage” across the rockies on a budget from the US federal government, but the people who 35 years later followed their path via wagon train in order to build homes there, went on their own nickel. History teaches strong lessons about the difference between “exploring” and “pioneering”.

The goals of space advocates are not the goals of any existing national program, nor is it likely that they should be. After all, the ones who benefit most from space settlement will be the settlers, not the original nations on Earth.

The difference between an “outpost” and a “settlement” is raising kids. The most successful colonies in history were colonies composed not of carefully selected professionals, but of families. Yet, even the most ambitious NASA spaceflight proposals do not include this crucial factor. If a wealthy civilian like Dennis Tito, of consenting age, clearly sound in body and mind, could stir up so much political resistance from NASA, what will the reaction be to families with young children going into space? Frontiers are dangerous, and regardless of the level of understanding of the pioneers themselves, the fear of a “public relations incident” would surely be overwhelming to a politically sensitive government agency.

Families, self-selected, not by individual qualifications but by those ineffable and “irrational” processes we know as love and romance, are not on the radar at NASA

Families, self-selected, not by individual qualifications but by those ineffable and “irrational” processes we know as love and romance, are not on the radar at NASA, where tough “professionals” sacrifice family life to fulfill their “duty” (or ambition). It’s not a settlement culture.

The colonies that succeed in space, like their predecessors on Earth, will be mostly self-funded, self-supporting organizations, eager to make that first break-even point where they can feed themselves from their own effort, because their futures will depend on it. And once they overcome those first obstacles, they will be the ones who reap the benefits.

Free-licensed design, the bazaar methodology, and a hands-on culture of freely-shared information and personal self-sufficiency provide an indispensable fusion of frontier sensibilities with the high-tech environment of the space pioneer

Proprietary, big-risk entrepreneurial enterprises may make people on Earth rich; NASA and other government programs may support research that benefits their nations; but the real business of building new settlements and new nations in space will fall upon the settlers themselves. Free-licensed design, the bazaar methodology, and a hands-on culture of freely-shared information and personal self-sufficiency provide an indispensable fusion of frontier sensibilities with the high-tech environment of the space pioneer.

Will it really be NASA that figures out how to make an airlock that is sufficiently child-proof so that little three-year-old Sally doesn’t space herself and her whole family as she imitates her parents’ button-pushing skills? Personally, I’m betting it will be Sally’s mom that figures that out.

Bibliography

[1] Bettyann Holtzmann Kevles Almost Heaven: The Story of Women in Space, MIT Press March 2006, ISBN 0-262-61213-5.

2(http://www.freesoftwaremagazine.com/articles/free_matter_economy_2)

3(http://www.tucsonspacesociety.org/isdc2000/index.htm) was the 19th annual International Space Development Conference

4(http://www.tucsonspacesociety.org/isdc2000/track2.htm) was a conference organizer and an active member of “Tucson L5”/“Tucson NSS”

5(http://ipinspace.gsfc.nasa.gov/documents/OMNIconcept.pdf), PDF format

6(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISRU) (definition from Wikipedia)

[7] Robert Zubrin, Mars Direct

[8] Gerard K. O’Neill, The High Frontier, 1977 (1st ed./Space Studies Institute), 2000, ISBN 1-896522-67-X (3rd ed./Apogee Books)

[9] A reiteration of the ‘four freedoms’ of free software: Free Software Definition

10(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christa_McAuliffe) was to be the first civilian school teacher in NASA’s “Teacher in Space” program, but died in the Challenger accident, after which NASA abandoned the idea of sending non-astronauts into space

[11] Space Frontier Foundation: Let Tito Fly!

[12] Space Frontier Foundation: Keep Mir Alive

[13] Tom Jaquish, Where are the spacesuits?

[14] Peter Koch, M is for Middoors, Moon Miner’s Manifesto #5

15(http://www.astronautix.com/craft/reseball.htm)

16(http://www.space-frontier.org/Projects/CatsPrize) is a popular catchphrase in the space community and has motivated projects such as the X-Prize

[17] Ethically, of course, this is a good thing—space colonization will not displace anyone, unlike the Western expansion of the United States. This is an important failure of the popular “American West” analogy. Perhaps Carl Sagan’s suggested analogy (in Cosmos) of the colonization of the Polynesian islands is more apt.

18(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biosphere_2) (Wikipedia)

19(http://www.siteselection.com/ssinsider/snapshot/sf040405.htm) (summary of the history in Site Selection magazine)

[20] Minnesota Lunar Simulant can be ordered from Dr. Paul W. Weiblen, the Director of the Space Science Center, 103 Shepherd Laboratories, 100 Union St., U. of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. 55455, according to this Lunar Reclamation Society story

21(http://www.asi.org/adb/02/02/)

22(http://www.pubs.asce.org/WWWdisplay.cgi?9603157)

23(http://www.asi.org/adb/02/16/01/01/glass-fiber-textiles.html)

24(http://www.asi.org/adb/06/09/03/02/096/lunar-glass-production.html)

25(http://www.asi.org/adb/06/09/03/02/106/lunar-studies-part1.html)

[26] Peter Koch, Moon’s Thorium May Unlock Gates to Mars (PDF), Moon Miner’s Manifesto #113.

27(http://www.asi.org/adb/02/13/02/silicon-production.html)

28(http://www.pythom.com/story/RobonautstohelphumansinspaceMay252005.shtml)

[29] The Crew Spider project was not finally published, but was another motivator for this research into community-based peer production methods and research funding.

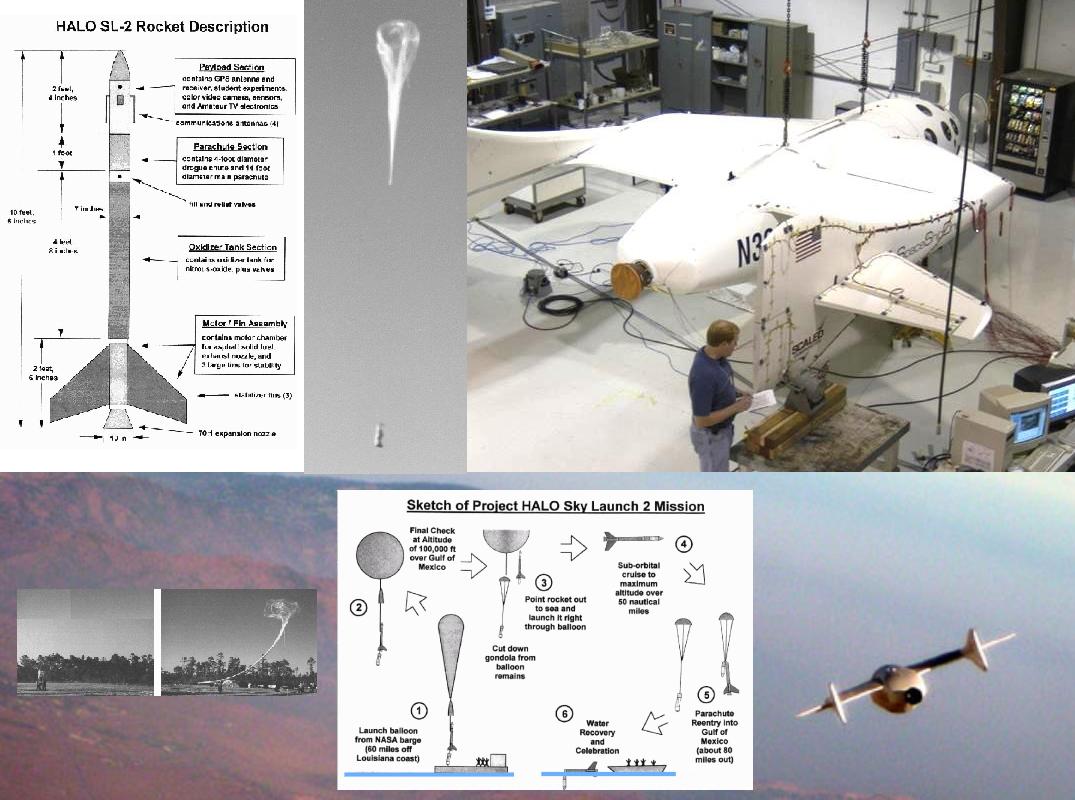

30(http://hiwaay.net/~hal5) and Project HALO

[31] HAL5, The HALO/SpaceShip One Connection (press release)

[32] Richard Stallman, The GNU Manifesto