You might think that a good program is all about good programming. But for a number of applications, the barrier to success isn't programming at all. Some of the most interesting projects nowadays -- speech recognition, for example -- rely on machine-learning from databases of information. It's not enough to write free software for these applications, we have to also provide that software with the right data. Contributing to these projects is needed from a much larger group of people, but it also can be very easy to do.

Speechless

Recently, I was asked by a friend for recommendations on voice-recognition software. As always, I started by looking for free software. But as I feared, this turned out to be one area where free software applications lag far behind their proprietary counterparts. In the end, I wound up recommending sticking with a proprietary Windows application as his best option at present -- and that never sits well with me.

But as I feared, this turned out to be one area where free software applications lag far behind their proprietary counterparts

Why is this? Is it because of a lack of expert programmers? Not enough scientific understanding of the human voice or speech?

No.

According to VoxForge, which has been working on this problem, it's because speech recognition software relies heavily on "speech models" -- mathematical descriptions of the link between the sounds we make and the words we actually mean. This is a very complex job that our nervous systems are finely-tuned to do. But even we aren't born with this capacity, we learn it -- typically during the first year or two of life.

Speech recognition software relies heavily on "speech models" -- mathematical descriptions of the link between the sounds we make and the words we actually mean

In fact, the fact that we typically learn it entirely from people speaking one language in one local dialect is the reason why we grow up to unconsciously speak with an accent. We also have difficulty parsing the sounds of foreign languages -- the infamous "R"/"L" problem for Japanese speakers learning English, or the very similar problem with "D"/"DH" for English speakers learning Hindi.

How much worse must it be for a machine?

The truth is that the learning problem itself is largely conquered. Algorithms are known, and competent programmers can code software to apply them. But the actual speech -- in a machine-readable form (recorded speech) with machine-readable interpretation (text of the speech) supplied -- is not nearly so abundant.

Time to speak up!

There are some sources, of course -- for example, there are a number of Project Gutenberg public domain texts which have been read aloud, primarily for entertainment/educational purposes. Sites like LibreVox have provided many of these recordings, which come from volunteers who need no more than a computer with a microphone to do the job.

One thing to realize about this is that there's no need to be a professional speaker or reader to be valuable to this kind of program

One thing to realize about this is that there's no need to be a professional speaker or reader to be valuable to this kind of program. Even if (maybe even "especially if") you have verbal tics or speech habits that are less than ideal for a professional speaker, your contribution is still valuable for use in building speech corpora to train recognition engines. Because, of course, the point of the training is to be able to handle a wide range of human speech.

So I decided to contribute to VoxForge's database.

Using the Java applet

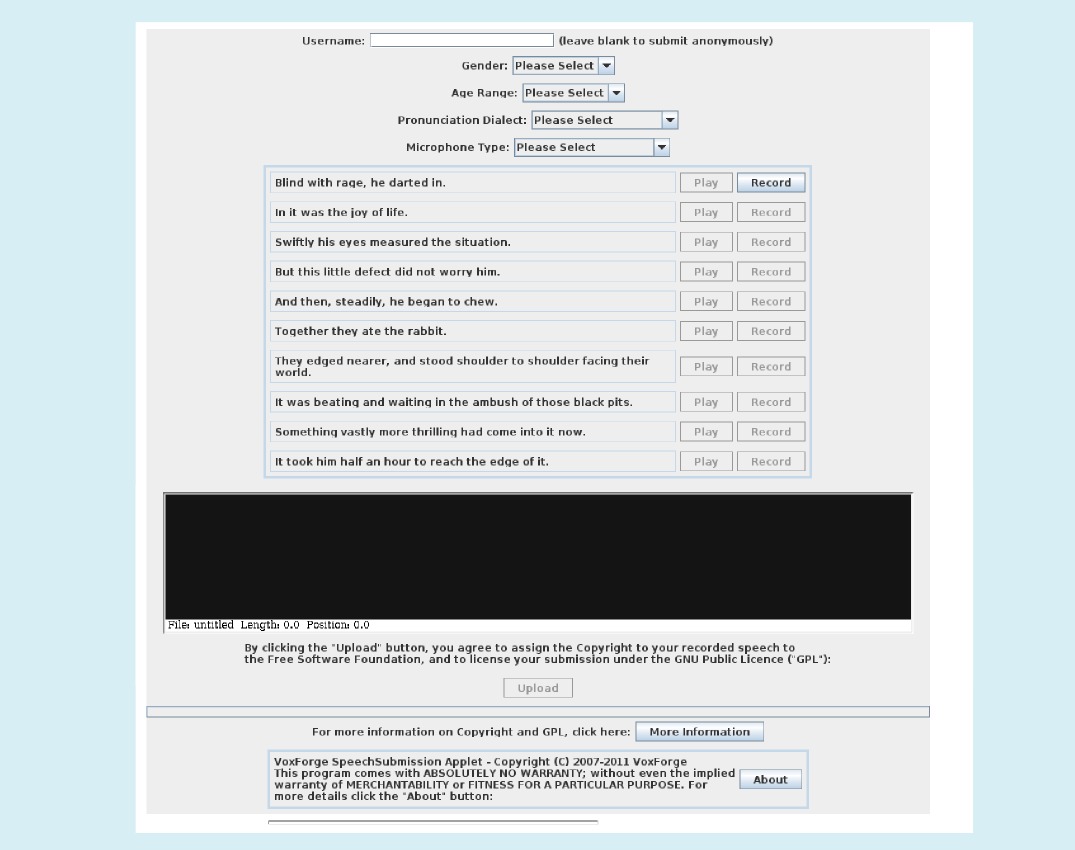

I tried the Java applet for recording speech samples, but it didn't work for me. Maybe it will for you. It is supposed to automate the process of recording lines of text from the audio prompts, taking care of the organizational details of attaching the speech to the right text (See the figure below). However, it's a trusted Java application in browser, and it's apparently somewhat finicky about audio drivers.

So I decided to try the offline-recording approach with Audacity.

Using Audacity

This is a little more tedious, since, after recording, you'll have to do a little organizational work with the data, but they've made it pretty simple, taking advantage of the "Export Multiple" feature in Audacity. Although there are complete instructions on the VoxForge site, I want to summarize the process here:

Register an account

This isn't strictly required, since VoxForge does accept anonymous submissions, but it's useful because it will allow them to keep your voice files together, which is better for training purposes. It's a simple email-address, username, and password registration, and of course, you can use a pseudonym if you want.

Select and open a prompts file

Two broad categories of prompts are provided: "Dialect Coverage" and "Phoneme Coverage". You should start out with the "Dialect" prompts and move on to the "Phoneme" afterwards if you want to continue. There are separate sets of prompts in each -- this is basically a batch of lines of text for you to record.

Once you've selected the file, you should open it in your browser, and position it for easy reading alongside Audacity.

Launch and configure Audacity

Start up Audacity (install it first, if you haven't already -- most major distributions will already have it packaged for you). Go to the Edit->Preferences menu. Under "Devices", you'll want to make sure that your microphone is set up as the recording device. Under "Quality", you'll want to set the audio to 16-bit and the sample rate to 48,000 Hz, if your equipment supports it. Save these settings, and restart Audacity to make them the default settings.

After re-launching, make sure the microphone is turned up, and test your recording level:

- Make the room as quiet as possible

- Set the microphone close to your mouth, but not directly in front (this an easy trick to avoid popping sounds).

- Push the record button in the Audacity interface and record your first prompt as a test.

- Adjust your position relative to the microphone, and if necessary, adjust your sound mixer, to get the envelope from your speech to average around 0.3, with peaks near 0.5. Anything above 1.0 will get clipped (the numbers represent the digitizable range), and you want to avoid that.

- Delete the test track and repeat, until you are satisfied

Record the prompts

Now, you'll record one prompt in each track, in order. So, read the first prompt, then hit "stop". Then hit "record" and record the second prompt into the second track. Repeat this until you've read all the prompts -- each into a single track in Audacity. The number of tracks should be the same as the number of lines in the original set of prompts.

Export the tracks to separate files

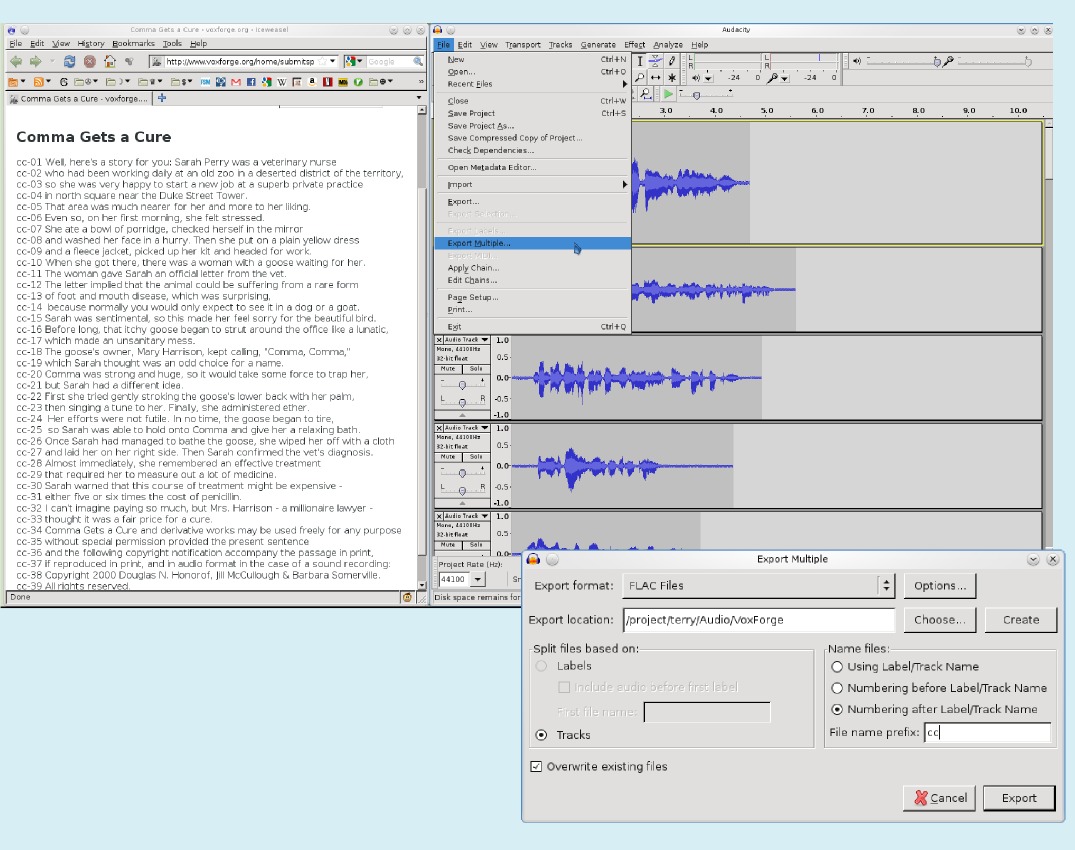

At this point, you should have an Audacity project consisting of a bunch of tracks of recorded prompts. You might want to save this as an Audacity project at this point. But for submission, you'll want to use the File->Export Multiple option to export the tracks to a bunch of files. You'll need to choose "FLAC" or "WAV" as the output format, and you'll want to use the "numbered" filenames option. Provide the stem that appears alongside each prompt in your prompts file. For example, mine started with "cc-01", and so I entered "cc" as the stem (this is the code for "Comma Gets a Cure", one of the sample pieces).

Packaging the files for upload

Now, you'll have a directory full of audio files. You'll need to create a "README.txt" and a "LICENSE.txt" file to go with them. The VoxForge site provides templates for these, though, so that part is easy. The "LICENSE.txt" file just asserts that your samples are covered by the GNU General Public License, while the "README.txt" file provides some technical details about your recording.

Make a tarball

Next, you'll make a compressed ".tgz" tarball package. I put my files into a subdirectory, and then archived that:

$ mkdir Digitante-20110303-cc

$ mv *.flac *.txt Digitante-20110303-cc/

$ tar zcf Digitante-20110303-cc.tgz Digitante-20110303-cc

Upload the tarball

After you've packaged up your speech files, you can then upload them via VoxForge's submissions page, which finishes the process.

Or... Read a book!

Although these targeted prompts are probably the highest quality contribution to VoxForge, there is another, perhaps more entertaining approach, and that is to simply read one of the many available public domain texts. This also serves dual-duty, because you'll be contributing both to the speech corpus available for training VoxForge's voice-recognition software, but also to a growing body of free culture audiobooks. These can be shared through several sources, including LibreVox.

This also serves dual-duty, because you'll be contributing both to the speech corpus available for training VoxForge's voice-recognition software, but also to a growing body of free culture audiobooks

The one major concession that VoxForge asks for is that you provide them with an un-processed, lossless copy of your recording (in FLAC, WAV, or AIFF format). There is a separate submissions process for audiobooks, partly due to the larger filesizes involved.

Promoting freedom of speech

I hope that someday, when my friends ask, I'll be able to point to a reliable free software voice recognition system, based on the work VoxForge is doing. This will require a lot of contributions of speech tracks, but contributing them is actually very easy. This a perfect opportunity if you've been wanting to contribute to free software without having to learn to program! For this, all you need is a computer, a microphone, and your voice.

Licensing Notice

This work may be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, version 3.0, with attribution to "Terry Hancock, first published in Free Software Magazine". Illustrations and modifications to illustrations are under the same license and attribution, except as noted in their captions (all images in this article are CC By-SA 3.0 compatible).