In this article, I respond to Robert McHenry’s anti-Wikipedia piece entitled “The Faith-Based Encyclopedia.” I argue that McHenry’s points are contradictory and incoherent and that his rhetoric is selective, dishonest and misleading. I also consider McHenry’s points in the context of all Commons-Based Peer Production (CBPP), showing how they are part of a Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD) campaign against CBPP. Further, I introduce some principles, which will help to explain why and how CBPP projects can succeed, and I discuss alternative ways they may be organized, which will address certain concerns.

Introduction

Recently, a friend of mine passed a rather noteworthy online article my way. The article, published in Tech Central Station, was entitled “The Faith-Based Encyclopedia,” and was written by Robert McHenry [McHenry, 2004]. McHenry, the Former Editor in Chief of the Encyclopedia Britannica, was quite critical of Wikipedia in this article. Perhaps this comes as no surprise to readers who are already detecting the potential for a slight conflict of interest here. Still, I expected to learn something from this article, as Wikipedia is not perfect, and McHenry seemed like a reputable individual. Instead, I was greeted with an onslaught of FUD that left me flabbergasted. I can honestly say I learned nothing from “The Faith-Based Encyclopedia.”

The goal of FUD is to make money when the free software competition cannot be defeated fairly in the marketplace

For the uninitiated, FUD stands for “Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt.” It is a term popular within the free software community, used to describe the use of lies and deceptive rhetoric, aimed chiefly at free software projects. It is an accurate term. In brief, the goal of FUD is to make money when the free software competition cannot be defeated fairly in the marketplace. This can be done by scaring consumers through wild propaganda, or more recently, confusing courts through more subtle arguments.

Foremost in the FUD hall-of-shame are figures such as Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and SCO Corporation CEO Darl McBride. CEOs such as Larry Ellison and Scott McNealy advance FUD from time to time as it suits them, but are not as single-mindedly unrelenting as the worst of the bunch. For more information on these gentlemen, their claims, and the truth, I refer you to web logs such as Slashdot, Lawmeme, and Groklaw.

McHenry’s article is not so much remarkable for its own points (which I dissect below) as for the reaction to it. Most people, even those who know Wikipedia well, seem to lack confidence regarding its role in society. Even Larry Sanger, a former project member and co-founder of Wikipedia, largely defers to McHenry’s sentiment [Sanger, 2004]. Sanger goes as far as suggesting Wikipedia needs to be more elitist (note how he doesn’t say more meritorious ), which would explicitly undermine the value of the project. I know other, very intelligent people, who had a “gosh, what were we thinking” reaction to McHenry’s article, as if an angry god had come down from upon high to punish them for falling astray.

These arguments are a new kind of FUD, aimed not just at open source software, but at any form of free or open resource

Some of this attitude is understandable—Wikipedia is so new that most people don’t know what to make of it. However, people like McHenry, with a vested interest or deep-seated bias, are ruthlessly taking advantage of this trepidation. I would implore everyone to weigh their own experiences in the matter much higher than the abstract arguments of third parties.

In the case of McHenry, I believe that these arguments are a new kind of FUD, aimed not just at free software, but at any form of free or open resource. I will make the case that there are in fact no terminally fatal shortcomings in Wikipedia, and that Robert McHenry is a pioneer of this new world of FUD, rightly deserving a spot next to Ballmer and McBride in the FUD pantheon.

Introduction to Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a collaborative, internet-based encyclopedia, made up of individual (but interconnected) entries. Anyone can create an entry for the encyclopedia, and anyone else can come along and edit existing entries. The intent is to tap the power of the general internet community’s knowledge and the desire to share that knowledge, to build a free, high-quality, comprehensive online encyclopedia.

At first blush, it might seem like this could not work, and that the result would be a chaotic mess. But it does work. This is true due to a number of features of the collaborative system (mediawiki) and underlying social dynamics. I will discuss these later.

Wikipedia is almost becoming authoritative, a fact which clearly upsets McHenry and similarly-situated individuals

Wikipedia is a good resource. In fact, it is an incredible resource. As a frequent user of Wikipedia, I believe I am qualified to make this determination. Hardly a day goes by without my accessing a handful of Wikipedia articles, either from a web search, forwarded by a friend spontaneously or in reference to a conversation we have had, linked from other Wikipedia articles, or accessed directly in an ad hoc fashion.

I have noticed recently that Wikipedia is being invoked more, and contains more articles of a higher quality than in the past. Further, I cannot remember the last time I accessed a Wikipedia article that was not of apparent professional quality. Indeed, Wikipedia is almost becoming authoritative, a fact which clearly upsets McHenry and similarly-situated individuals.

I have never used an encyclopedia as much as Wikipedia and I thank the Wikipedia community for what they have created. Countless others share these sentiments. Wikipedia has enhanced my life and brought considerable progress to society. I consider these facts so easy to demonstrate that they are pointless to debate.

It is into this milieu that McHenry’s article arrives. Suffice it to say, I find his attitude and claims a little surprising, given the above observations. Those I know who are involved with Wikipedia do not seem to have received the same memo on the imminent collapse of their project. But as Görring once said, the bigger the lie, the more people who will believe it. I think this is what McHenry is shooting for.

Response to McHenry

McHenry’s central thesis is that, quite contrary to general observation, Wikipedia is a poor-quality resource, that it is in a constant state of chaos, and that these problems will tend to get worse over time. Of course, he doesn’t explain how one is to reconcile this claim with the increasing popularity of Wikipedia, other than a veiled suggestion that people are simply stupid.

McHenry begins his article with a proof-by-denigration. He takes the entire proposition, that a commons-based collaborative encyclopedia could even be successful, as ridiculously out-of-hand. He recounts Wikipedia’s failed first start as “Interpedia,” which I presume is done to poke fun at the concept, the people, and the community process behind Wikipedia. Then, in heavily loaded terms, he characterizes the claim of increasing quality as (emphasis added):

Some unspecified quasi-Darwinian process will assure that those writings and editings by contributors of greatest expertise will survive; articles will eventually reach a steady state that corresponds to the highest degree of accuracy.

He then goes on to say:

Does someone actually believe this? Evidently so. Why? It’s very hard to say.

Actually, I don’t believe it is so hard to say, and will go into detail on the matter shortly.

McHenry then goes on to theorize that the currently-vogue educational technique of “journaling” is responsible for corrupting the thinking of today’s youth, consequently leading them to believe in something as ridiculous as the success of collaborative commons-based projects. I can only surmise that this bizarre tangent is due to a pet peeve of his, and believe it can be safely discarded.

Our friendly author then takes a stab at empirics. His method is to sample a number of Wikipedia entries, inspecting their previous versions and revision history to ascertain whether the quality has increased or decreased. The size of McHenry’s sample set is: 1.

At this point, it is worth noting that Wikipedia recently reached the 1 million article mark.

About this dubious empirical method, McHenry says:

…I chose a single article, the biography of Alexander Hamilton. I chose that topic because I happen to know that there is a problem with his birth date, and how a reference work deals with that problem tells me something about its standards.

So in other words, he is quite cognizant of the fact that he is about to make an induction from one article to one million, based on a degenerate case. I will temporarily leave the reader to make their own value judgment of this policy, and proceed within the bounds of McHenry’s game.

McHenry finds two problems with the Hamilton article. The first is that it gets a date wrong. The second is that it has declined in quality over time, at least, according to his standards. McHenry’s definition of quality seems to consist solely of presentational matters such as spelling, grammar, and text flow. These are of course important considerations, but I propose that there are other important facets of quality—for example, coverage. In a later section, I will attempt to sort out some of the confusion on this topic. For now, let us again take McHenry’s claims at face value, and proceed to the finale.

He concludes with a metaphor. I will reproduce it here in full (emphasis mine again):

The user who visits Wikipedia to learn about some subject, to confirm some matter of fact, is rather in the position of a visitor to a public restroom. It may be obviously dirty, so that he knows to exercise great care, or it may seem fairly clean, so that he may be lulled into a false sense of security. What he certainly does not know is who has used the facilities before him.

McHenry is essentially asking us to suspend all higher brain function at this point: in the above metaphor he simply pretends that the reviewability features he just based his entire analysis on do not exist.

A reminder is perhaps in order: to determine that his not-so-randomly chosen article declined in quality, McHenry used Wikipedia’s revision history feature to look at how it had changed over time. This feature of Wikipedia, which is a hallmark of open content production systems, makes it precisely the opposite of a public restroom. You can in fact see everything that “came before you” with Wikipedia.

Public reviewability would be _embarrassing_ to traditional content creators

What would McHenry’s metaphor apply more fittingly to?

Why, a traditional print encyclopedia, of course. If I wanted to analyze an arbitrary Britannica article’s evolution over time (for example), I’d have to somehow acquire the entire back catalog of the Britannica (assuming older editions can even be purchased), presumably reserve a sizeable warehouse to store them all, and block out a few days or so of my time to manually make the comparison.

Even the electronic forms of traditional encyclopedias are sure to be lacking such reviewability features. This makes sense, as public reviewability would be embarrassing to traditional content creators.

So, in an artistic twist of doublespeak, McHenry has attempted to convince the reader that one of the key failings of traditional, closed media is actually the main problem with open, collaborative content. Presumably, love is also hate, war is peace, and so forth.

As if this was not enough, there were some other asides and general themes of his article that scream “FUD,” or simply boggle the mind by virtue of their illogic.

For example, McHenry makes a point that seems like it should, by all rights, completely discredit his own article. He says (emphasis added):

I know as well as anyone and better than most what is involved in assessing an encyclopedia. I know, to begin with, that it can’t be done in any thoroughgoing way. The job is just too big. Professional reviewers content themselves with some statistics—so many articles, so many of those newly added, so many index entries, so many pictures, and so forth—and a quick look at a short list of representative topics. Journalists are less stringent.

So in other words, no one can conclusively assess an encyclopedia. This is an odd thing to say before proceeding to assess an encyclopedia. McHenry also fails to meet even the approximate standard of his “professional reviewers,” unless you seriously consider examining one article to be statistically significant. Personally, I think routine use, amortized over millions of people, can actually shed some light on quality.

You “never really know” if a Wikipedia article is true... but _this is also the case for traditional encyclopedias..._ no one in their right mind would claim that traditional encyclopedias are perfect

An important underlying theme of McHenry’s piece is his repeated harping on the fact that you “never really know” if a Wikipedia article is true, and his jeering at the Wikipedia community for honestly admitting this. Simultaneously, he utterly ignores the fact that this is also the case for traditional encyclopedias. Once again, this is a purely rhetorical device, as no one in their right mind would claim that traditional encyclopedias are perfect.

I am of the school of thought that when you critique something for which there are alternatives, you should apply the same review criterion to the alternatives as you do to the main subject. Perhaps McHenry is just not a student of this school.

To sum it all up, the majority of McHenry’s piece is laced with snide, pejorative, and in general, loaded words and statements. Many of his points undermine his core claims, but his argument-through-sentiment goes a long way towards leaving a negative impression of Wikipedia on the reader. This is a shame, and I hope that few people are dissuaded from using or contributing to the resource for this reason.

In the next section, I will address the following serious (but only implicit) claims of McHenry:

- Individual article quality in CBPP systems will inevitably (and monotonically) decline.

- The quality of the entire CBPP resource will decline.

- There is only one facet of quality that matters.

Understanding CBPP

Commons-Based Peer Production refers to any coordinated, (chiefly) internet-based effort whereby volunteers contribute project components, and there exists some process to combine them to produce a unified intellectual work. CBPP covers many different types of intellectual output, from software to libraries of quantitative data to human-readable documents (manuals, books, encyclopedias, reviews, blogs, periodicals, and more).

Even commercial sites, such as Amazon.com, have significant CBPP elements nowadays

Examples of successful CBPP efforts abound. The Linux kernel, the GNU suite of software applications, and the combined GNU/Linux system are prime examples of software CBPP. Slashdot.org is an important example of CBPP through submission of the news articles, and more importantly, the collaboratively-based comment filtering system. Kuro5hin.org is an example of a collaborative article and current-events essay blog, with an emphasis on technology and culture. Wikipedia is an example of a comprehensive encyclopedia.

Even commercial sites, such as Amazon.com, have significant CBPP elements nowadays. These manifest in Amazon as user-submitted reviews and ratings and interlinked favourites lists.

The enabling dynamic of CBPP is that people are willing to volunteer a little bit of work and a large amount of knowledge to online community systems, and that when this force is properly harnessed, significant overall value can be created.

This trend has not gone unnoticed, or unexplained.

In fact, the term CBPP was coined by Yochai Benkler in his seminal work “Coase’s Penguin: Linux and the Nature of the Firm” [Benkler, 2002]. In this work, Benkler acknowledges that CBPP is a real and common phenomenon underlying many important intellectual efforts in the world today, and attempts to answer “why” and “how.” Benkler explains why CBPP happens in terms of a simple economical analysis, which reveals that CBPP is a new mode of production, existing alongside markets and firms as a productive modus operandi.

However, I think there are some details about how CBPP functions that have not been summarized anywhere. Accordingly, I’d like to propose a pair of laws, which I believe apply to collaborative, commons-based production, and explain why Wikipedia and other CBPP efforts succeed. We could call them the “first two laws of CBPP:”

When positive contributions exceed negative contributions by a sufficient factor in a CBPP project, the project will be successful

- (Law 1.) When positive contributions exceed negative contributions by a sufficient factor in a CBPP project, the project will be successful.

This factor probably has to be greater than two in practice, because each negative contribution needs a proportional amount of work to be un-done. In other words, the project success criterion is p > an, where a > 2, and p and n represent positive and negative contribution quantity, respectively.

My guess for an approximate, “universal” minimum value of a would be about 10. This value probably has to be much greater than the theoretical minimum (2), because people in social settings will be annoyed and demotivated by a smaller quantity of adversity than is actually insurmountable. In general, contributors don’t want to be spending a significant amount of their time treading water and backtracking. For example, if p / n = 3, then 33% of positive contributions are not going towards permanently improving the product.

However, I would bet that the positive-to-negative contribution ratio in many collaborative projects exceeds levels of 100 or 1000. In principle, the approximate value could be discovered empirically for particular projects. This would be a very interesting study to undertake.

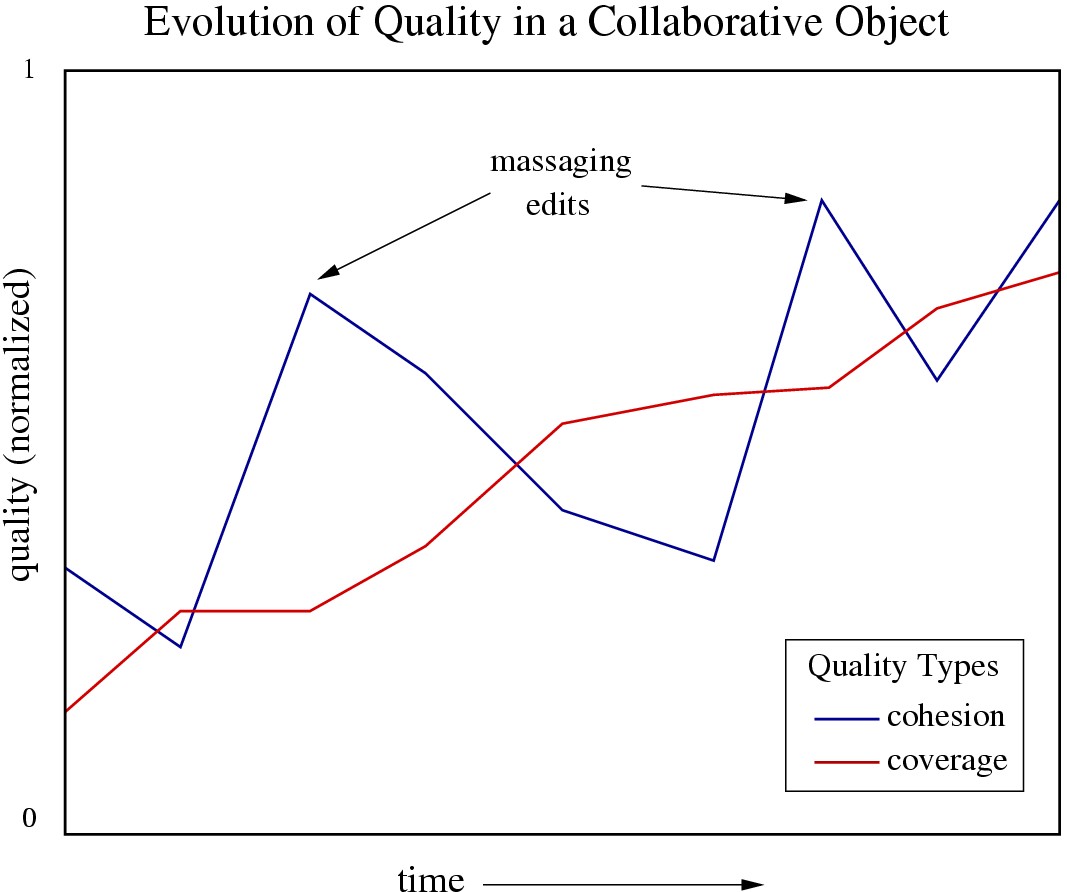

- (Law 2.) Cohesion quality is the quality of the presentation of the concepts in a collaborative component (such as an encyclopedia entry). Assuming the success criterion of Law 1 is met, cohesion quality of a component will overall rise. However, it may temporarily decline. The declines are by small amounts and the rises are by large amounts.

This phenomenon can be explained by the periodic, well-meaning addition of new conceptual materials by disparate individuals. These additions are often done without much attention to overall presentation (i.e., pedagogy, terminology, flow, spelling, and grammar). However, when these problems become large enough (with respect to a single project component), someone will intervene and make a “massaging edit” that re-establishes the component’s overall cohesion.

To this I also add a companion corollary:

- (Corollary.) Laws 1 and 2 explain why cohesion quality of the entire collection (or project) increases over time: the uncoordinated temporary declines in cohesion quality cancel out with small rises in other components, and the less frequent jumps in cohesion quality accumulate to nudge the bulk average upwards. This is without even taking into account coverage quality, which counts any conceptual addition as positive, regardless of the elegance of its integration.

I think these laws take a lot of the mystery out of Wikipedia. The intent here is not to diminish the achievement, but to help us understand how it can be so. Thoughtful people tend to expect a tragedy of the commons when considering any commons-based production effort, but CBPP defies this expectation. I have learned to accept and embrace this reality, as have impartial observers such as Benkler. Others, such as McHenry, have not. Perhaps this conceptual framework would help them move on.

Other Styles of CBPP

Wikipedia does not embody the only model for CBPP. In fact, there are numerous models, corresponding to the type of intellectual output being produced, as well as the characteristics of the specific community producing it. I believe it is important to distinguish between CBPP and specific models of CBPP, so as to allow people to make an educated decision as to whether to employ CBPP for their efforts. What is good for Wikipedia may not be the best model for your project.

McHenry bemoans the fact that anyone can edit a Wikipedia entry... but even if this was a legitimate problem, it still would not herald the downfall of CBPP

McHenry spends a lot of time in his article bemoaning the fact that anyone can edit a Wikipedia entry. While it is obvious that this modus operandi has not prevented Wikipedia from becoming a great success, it’s not necessarily so obvious that there are other ways to organize CBPP. So even if this was a legitimate problem, it still would not herald the downfall of CBPP.

In previous work [Krowne, 2004], I identified one of the key attributes of CBPP as the authority model. The authority model of a CBPP system governs who has permissions to access and modify which artifacts, when, and in what workflow sequence.

In that study, I outlined two authority models, the free-form model, and the owner-centric model. The free-form model, which Wikipedia employs, allows anyone to edit any entry at any time. Changes can of course be rolled-back, but they can also be re-applied. The ultimate guard against malicious behaviour is therefore the administrators of the site. However, ne’er-do-wells typically lose interest long before it is necessary to resort to administrative powers.

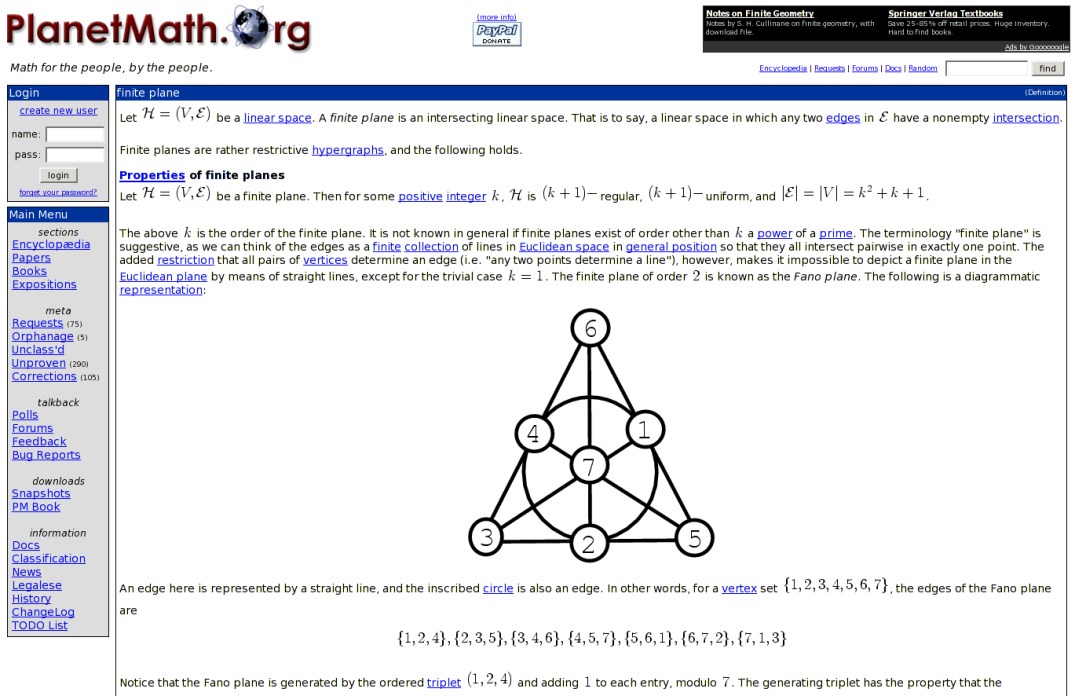

My own project, PlanetMath, employs the owner-centric model by default. In this model, there is an owner of each entry—initially the entry’s creator. Other users may suggest changes to each entry, but only the owner can apply these changes. If the owner comes to trust individual users enough, he or she can grant these specific users “edit” access to the entry.

These two models have different assumptions and effects. The free-form model connotes more of a sense that all users are on the “same level,” and that expertise will be universally recognized and deferred to. As a result, the creator of an entry is spared the trouble of reviewing every change before it is integrated, as well as the need to perform the integration. By contrast, the owner-centric authority model assumes the owner is the de facto expert in the topic at hand, above all others, and all others must defer to them. Because of this arrangement, the owner must review all modification proposals, and take the time to integrate the good ones. However, no non-expert will ever be allowed to “damage” an entry, and therefore resorting to administrative powers is vanishingly rare.

It is likely that these models have secondary consequences. A natural result of the free-form model may be that entries lack some cohesion, and perhaps may even be of lower overall quality, despite having high coverage. On the flip side of the coin, the owner-centric model can be expected to foster a high level of cohesion quality, but may actually lag in coverage due to higher barriers to individual contribution.

McHenry’s concerns can be translated into this framework, in which case he seems to be worried about the free-form model’s effect on entry cohesion quality. (There’s another interesting effect here: coverage quality is potentially less-bounded in digitized resources than in print ones, due to the near-complete removal of physical space limitations. Someone who only understands print resources—or has a vested interest in them—would therefore naturally de-emphasize the importance of coverage quality.) I don’t believe this is a legitimate concern for Wikipedia, given the success of the project and utility of the overall resource. In fact, in the study I conducted in [Krowne, 2004], I discovered that while concern about the free-form model was common, it was not clear that it had any negative impact on productivity.

Instead, it seems likely that the multiple facets of quality (cohesion vs. coverage, and perhaps others) play into a balance in overall entry quality, relative to the different possible authority models. McHenry’s concerns about cohesion quality might be more legitimate in other settings, or given a different balance of expertise, time available to volunteer, or malicious intent present. I believe further work needs to be done to study the issue of quality and CBPP authority models, as I suggested in [Krowne, 2004].

Conclusion

McHenry’s piece is full of so many contradictions of logic and sentiment that it is perhaps best understood (if you want to be charitable) as the train-of-thought reactions of someone personally upset by change.

According to McHenry:

- Wikipedia has achieved much (this is difficult to deny). On the other hand, it barely got started (hah!), presumably because of its CBPP nature.

- There are no truth-guarantees with any knowledge resource. On the other hand, Wikipedia is all junk written by high-schoolers, even when its content is not patently false.

- Wikipedia is honest and forward with its caveats (again, difficult to deny). On the other hand, it needs caveats (hah!).

- Clearly the popularity of Wikipedia is astounding and people are abandoning print encyclopedias for it and other internet resources. On the other hand, people are mindless sheep who will accept junk, so long as it is free.

If in fact intentional and premeditated, this article amounts to propaganda-like doublespeak that would make Orwell blush. The intent seems to be to leave people with a negative feeling about Wikipedia and other CBPP resources. Such an intent is difficult to prove prima facie, since McHenry mentions enough positive fact about Wikipedia to give himself and his ideological allies a basic line of defence. However, this defence crumbles upon further inspection.

In this article I have addressed McHenry’s actual points and implied complaints about CBPP, as well as introduced some descriptive principles of CBPP dynamics that help explain why the mode of production works. I hope these things help put the misconceptions and falsities propagated by McHenry and his ilk to rest. If this kind of FUD is required for traditional encyclopedias to survive in the future, then they will have rightfully earned the title “FUD-Based Encyclopedias.”

Bibliography

Benkler, Yochai “Coase’s Penguin: Linux and the Nature of the Firm,” Yale Law Journal, December 2002. online article

Krowne, Aaron, Bazaz, Anil “Authority Models for Collaborative Authoring,”’ HICSS 2004 Proceedings, January, 2004. online article

McHenry, Robert “The Faith-Based Encyclopedia,” Tech Central Station, November 15, 2004. online article

Sanger, Larry “Why Wikipedia Must Jettison its Anti-Elitism,” Kuro5hin.org, Dec 31 2004. online article