Over at Sphere of Networks, I published a text that tries to give a simple overview of the workings of information production in the age of the internet, covering everything from free software to free culture. This article is a slightly modified version of a chapter of this text. I will show how peer-to-peer file-sharing networks work and how Big Media tries to prevent this sharing by means of random lawsuits and by using DRM. What does this copyright war mean for consumers and for our culture as a whole?

Information technology

Since the 1970s computers have become ever faster, smaller and cheaper. This led to the availability of personal computers in most homes in the more economically developed countries. By 1995, the public started to realize the potential of the internet. Through the more recent introduction of broadband internet, most home computers are constantly connected to the internet at several times greater speeds than only a few years ago. Individuals have received the power to manipulate huge amounts of data ever faster, and (more importantly) to share the data they produce with others over the internet. Now it is possible for everyone to manipulate, for example, hours of homemade video and enhance it with some special effects. On the other hand, it has also become easy to mix and manipulate the works of others and share them with all the world, as demonstrated on sites like The Trailer Mash: here lots of people present new creative works they created—remixes of official movie trailers, rearranged to tell other stories. Use past cultural production to create something new. What only some lucky entrepreneurs like Walt Disney could do in the beginning of the 20th century, everybody can do today.

Networked computers enable individuals to manipulate huge amounts of data ever faster, and share the data they produce with others

Unfortunately, at the moment this is mostly illegal because of lengthy and restrictive copyright law. You can neither copy nor modify any work without the originator’s explicit permission. It isn’t like those derivative works were hurting sales of official movies or that nobody would listen to classical Mozart anymore (himself long dead) because his music was used and newly interpreted by a DJ. Nonetheless, copyright law has not been altered to let everyone make use of the new technologies. On the contrary, under the pressure of Hollywood and the Big Four record labels that dominate over 80% of the music market [1], copyright law has been tightened to prevent people from using these technologies. Under the pretext of protecting established artists’ revenues, new artists are prevented from rising. But the truth behind all this is that the record industry fears for its existence—rightly so.

File sharing

Today, some inexpensive home computers and the internet are superior to the distribution channels of the record industry with its CD manufacturing plants and many shops. Digital technology enables infinite copying of music and movies without any loss in quality.

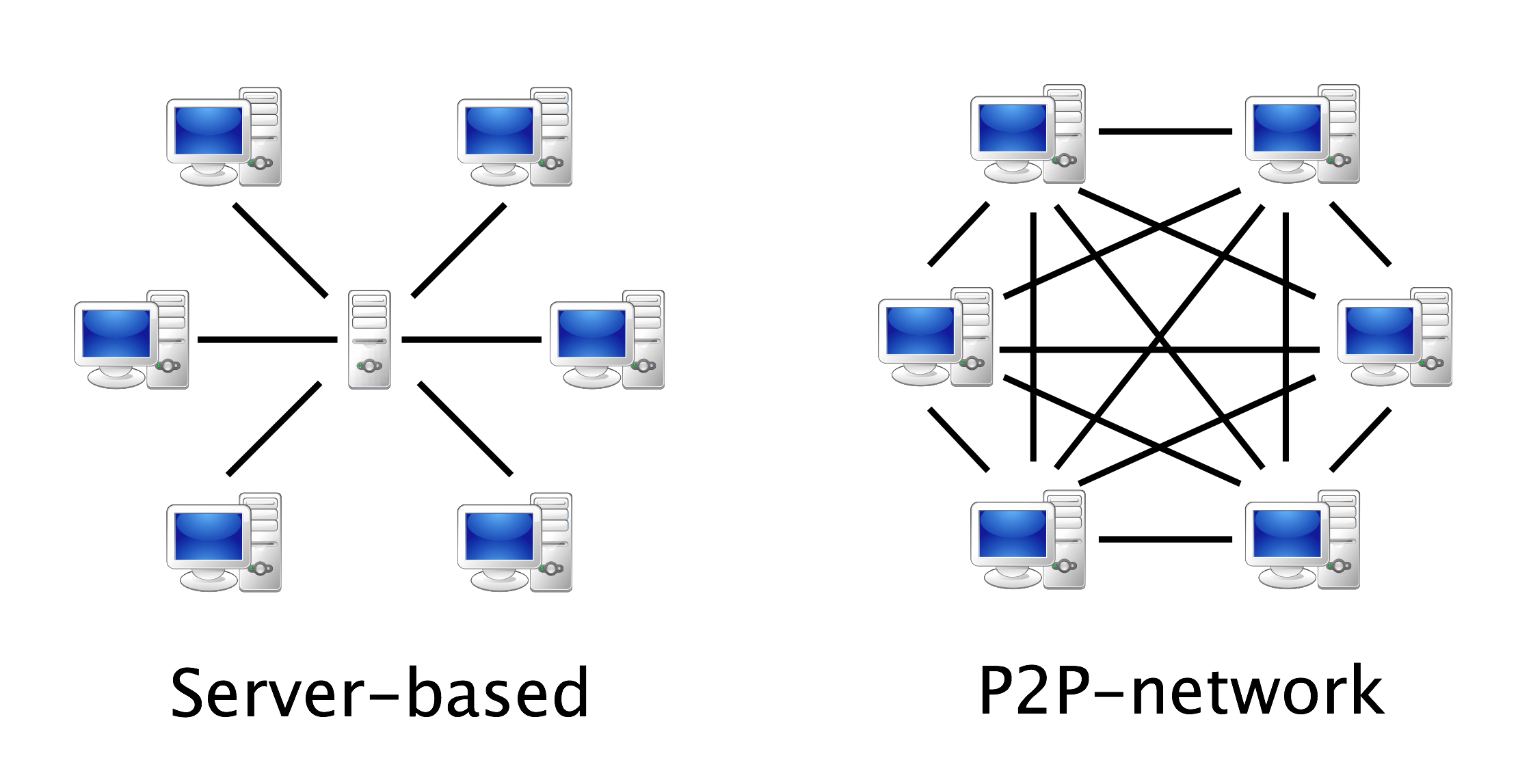

Shawn Fanning, a then 17 year old student, released Napster in 1999. It was the first peer-to-peer file-sharing system to gain widespread popularity for sharing music. In peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, the data isn’t stored on a central server and accessed by clients (which is the case with web pages), but many peers, usually ordinary home computers, share their data with one another. Soon this technology was adopted and improved; after Napster was sued by the record industry and ultimately shut down, new networks emerged which were even more decentralized. Every user downloading information is at the same time making available that very same information he/she just downloaded to other participants.

The most popular networks as of today are eDonkey2000 (with client-programs as eMule or MLDonkey), FastTrack (with clients as Kazaa or Grokster) and Gnutella (with clients as LimeWire or Gnucleus) [2]. While these networks are searchable through a client program, in the BitTorrent P2P network, data is found through websites like The Pirate Bay where a small .torrent-file is downloaded and then opened in a BitTorrent client such as Azureus or BitTornado, where the actual download takes place [3]. Most of this software is free software, but some is also proprietary.

Peer-to-peer networks are heavily utilized, millions of users all over the world share thousands of songs over the internet

These services are heavily used. Millions of users all over the world share thousands of titles and even rare songs they wouldn’t find in stores. The major music labels don’t like that and have come up with the term “Piracy”, equating people that share music with one another with bandits that attack other people’s ships. The record industry argues that every downloaded song accounts for a loss in CD sales which ultimately hurts artists. However, it should be kept clearly in mind that not every song downloaded would have been bought. Also through sharing samples, people are exposed to new music and might come to buy CDs they otherwise would never have known of. And downloading old material that isn’t available in stores anymore surely doesn’t hurt artists. It is also a fact that under the current model of music distribution, the average artist gets something between 5 and 14 percent of the CD sales revenue [4]. The rest trickles away in the business that is the record industry.

But now a new distribution model becomes feasible. Lots of ordinary people, connected through the internet, outperform the record industry and make it essentially obsolete in a time where high quality recording equipment to supplement home computers becomes ever cheaper. It simply isn’t necessary to buy physical records anymore. Especially for unknown artists, the internet represents a very attractive marketing ground; with services like Last.fm or Pandora, it has become very easy to discover new music. Artists who release their music can earn money by performing and going on tour (like artists always did before recording technology was invented). Alternative payments systems have also been proposed: mechanisms like an easy way to donate small amounts of money to musicians over the internet, or to let every person downloading pay a small monthly fee which is distributed to the artists based on their popularity. This could for example be done by bundling a voluntary fee with the broadband bill (Broadband, unlimited legal downloading included!) [5]. With these distribution and compensation methods, artists would most certainly be far better off than now, but the major labels aren’t willing to adopt yet. Instead they are fighting windmills, with all means available to them.

Lawsuits

As there is no single instance responsible for the operation of peer-to-peer file sharing networks, there is nobody in particular the music industry can sue. That’s why the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) turned to randomly suing people for copyright infringement that have allegedly participated in file sharing, in hope of deterrence. To find people in file sharing networks, they rely on tracing computer’s IP addresses. But it is often very difficult to find out who a specific IP belongs to and impossible to tell with certainty. That’s why the RIAA has already sued a 66-year-old grandmother for downloading gangster rap, but also families without a computer and even dead people were addressed [6]. The RIAA’s tactics are to intimidate defendants and force them into settlements outside the court under the threat that they are facing high legal fees.

But recently, victims of such random lawsuits began fighting back and countersued the RIAA for malicious prosecution [7]. But it continues to be an uphill-battle and non-profit organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which fight for digital rights and provide individuals with legal defense, have only limited resources compared to the large legal departments of the major record labels. To preserve its last-century business model, the record industry has actually turned to sue its own customers, something that’s only possible because a few companies hold a monopoly on about 90% of the music produced [8].

Copyright in a digital world

As video files are larger, downloading movies or TV series isn’t as common as sharing music yet, but it is only a matter of time when Hollywood will find itself in the same situation as the record industry is now. Social practices like going to the movies will remain popular in addition to watching films at home. As digital technology allows for ever cheaper production of videos and music, movies will eventually be produced at lower budgets than what is common in Hollywood today, but there will probably be more smaller films, oriented towards more specific audiences, than the homogeneous monster productions we are seeing today.

Copyright law was always meant to regulate copying. However, in the past this was something only competing businesses like other book publishers could do. But today, everyone can copy a file by a simple mouse-click. Thus the scope of this law has changed dramatically over time: from regulating anticompetitive business practices to restricting consumers. Keeping up these same rules in a digital world does nothing but label a large portion of citizens as criminals—for no obvious reason. Additionally, lots of creative works, which wouldn’t have been possible without inexpensive computers and the internet, are prevented from being published legally.

Today’s copyright law just doesn’t make sense when applied to digital technology

Today’s copyright law just doesn’t make sense when applied to digital technology. For example, it could even be argued that looking at a website is copyright infringement, as in order to display a webpage on the screen, the computer has to download it and make a local copy from the data stored on the server. As this is an unauthorized copy, this is actually illegal.

Not only has the scope of copyright changed dramatically, but also copyright terms have gone up like crazy. Copyright law is there to give authors the exclusive right to copy their works for a limited period of time. After that, copyright expires and the work passes into the public domain. Then everybody can make whatever use of it he wants without restrictions. This term was originally 14 years after the publication of the work. Since then however, it has been regularly increased. Through heavy lobbying from the record industry and Hollywood, since 1962, the U.S. Congress has extended copyright terms eleven times in 40 years alone. Today, in the United States, copyright persists for 70 years after the author’s death, and for corporate works it’s 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever is shortest.

DRM

Technology can also be used against people. Under the pretext of fighting “piracy”, the major entertainment companies have come up with ever stronger copy protections, all of them having something in common—they have been cracked very quickly [9].

In the ’80s, Hollywood was crying that home video recording would kill the film production. It didn’t, although you usually could easily copy VHS video tapes. On DVDs, copy prevention was already present from day 1. Now the industry is pushing new formats to protect HD video (high definition, resulting in a sharper picture) that are meant to replace DVDs. A standard hasn’t been reached yet and now two different optical disc technologies are fighting for dominance: BluRay and HD-DVD. Both implement new and stronger copy preventions which force the consumer to buy not only new players, but also new displays (so that Hollywood can even control the signal between the player and the display) [10]. Equipment has to be certified to be able to playback these media (as already the case with DVDs). Free software solutions are thus excluded from the system right from the start—in order to play DVDs on a GNU/Linux computer the copy prevention has to be cracked, which is done very quickly nowadays. However, even these new technologies, implemented in both BluRay and HD-DVD, have already been cracked by numerous methods, even before the discs get to consumers homes.

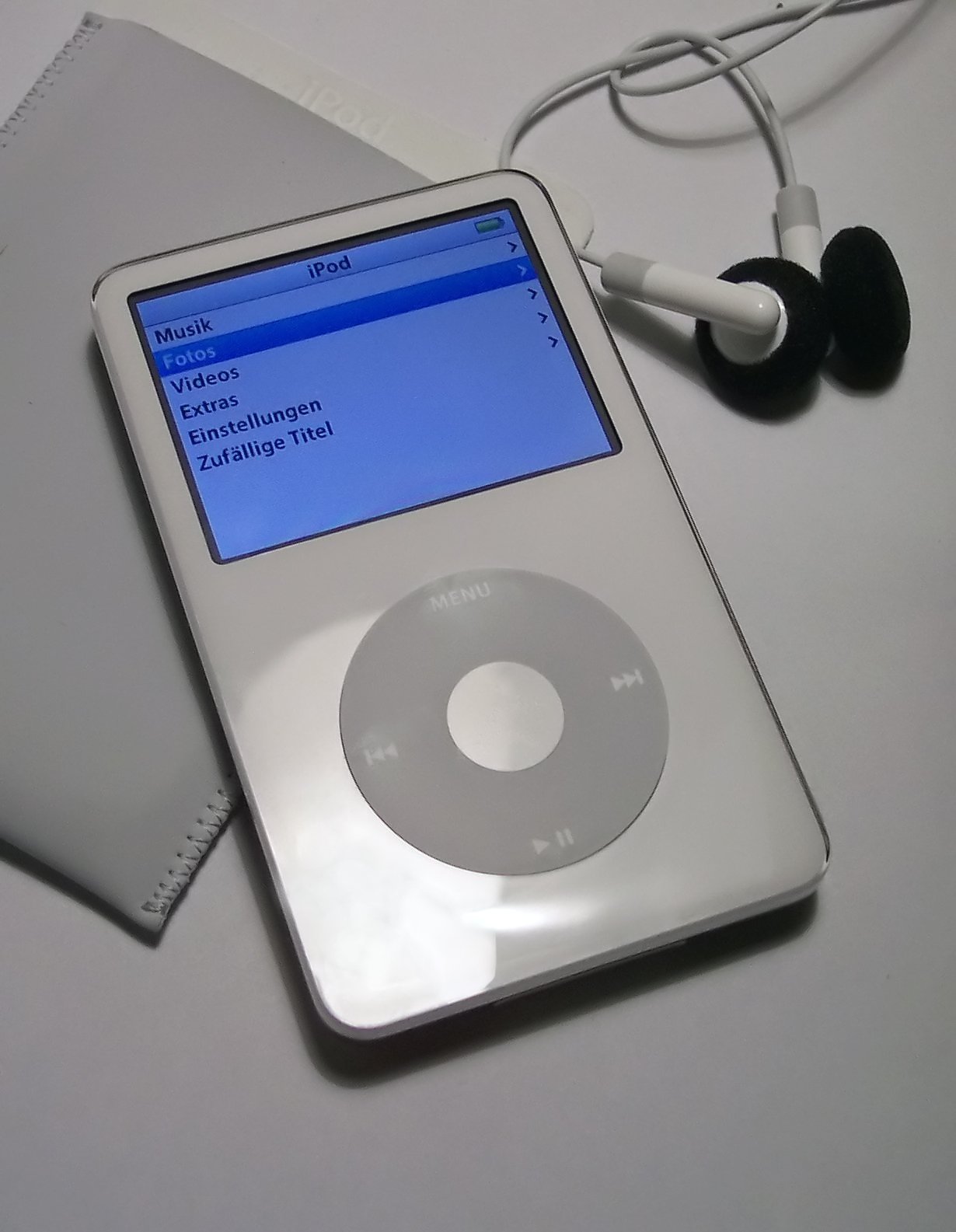

In the music market, the standard audio CD provides digital music of satisfactory quality to most listeners. CDs have been around for a long time, and stem from a time where copy prevention wasn’t common yet. There have been several attempts to implement copy preventions later on, resulting in audio CDs that some players couldn’t play which led to consumer frustration. With the rise of Apple’s iTunes Store, the music industry has slowly started to realize the possibilities of distributing music through the internet. Now people can buy songs and download them right away. The prices are comparable to CDs. Although virtually all distribution costs go away for the labels, artists don’t receive higher payments for the songs sold on the iTunes Store [11].

Music doesn’t just reside on a CD anymore: it is sold through the internet and transferred to portable music players like the iPod; the music industry cannot prevent their customers from copying it; as a result, the music industry developed technologies to limit access to music. For these new technologies, the umbrella term DRM is used. Originally standing for Digital rights management, opponents like the Free Software Foundation refer to it as Digital restrictions management. With DRM, the data, for example music or video, is digitally encrypted and can only be played back by specific devices or software. “Unauthorized copies” can be prevented or content can even be set to expire after a specific period of time. Songs purchased on Apple’s market leading iTunes Store for example bear the following (compared to others still relatively lax) restrictions: while the track can be copied on up to five different computers, playback is only possible with Apple’s iTunes software and on no other portable music player than Apple’s iPod. Music isn’t bought anymore, it is rather just rented for limited use.

Music isn’t bought anymore, it is rather just rented for limited use

It is also possible to sell sustainably DRM-free music over the internet (which can then be played back by any device including the iPod): stores like emusic which has currently 250,000 subscribers. However, the major record labels refuse to sell their songs without DRM, leading emusic and the likes to specialize in independent music.

As history has shown us, it is impossible to come up with a copy prevention or DRM system that is unbreakable. As long as the music and movie industries try to restrict access to the media they sell, they’ll be caught up in a cat-and-mouse game. Whenever a new DRM scheme sees the light of day, eventually it will be cracked by the many skilled people collaborating over the internet, and DRM-free copies will be available on peer-to-peer networks. However, it might one day become difficult enough for a large enough part of the population to set the media they paid for free. Consumers might just accept that they have only limited control over their legally bought music collection. That’s probably the goal of the entertainment industry. Not bringing “piracy” down, because they know that’s impossible, but controlling consumers to maximize revenue [12]. Then, because you can’t copy it and put it on an other device, the entertainment industry will be able to sell you the same song or video several times: once for your computer, maybe a second time for your portable music or video player, then for playback in your living room, and one more time as a ringtone for your cell phone.

To ensure that it’s difficult enough for most consumers, and first of all illegal, to crack the DRM on their media, additional laws were written. In the USA, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was enacted in 1998, in the European Union the EU Copyright Directive (EUCD) of 2001, which is similar to the DMCA in many ways. Now it is illegal to circumvent DRM or other access control technologies, even when copying the content was permitted under simple copyright law, for example under the terms of fair use (e.g. for means of citation, educational purposes or maybe using a tiny extract of the work non-commercially). Under the DMCA, even the production or spread of circumvention technologies was criminalized.

Implications

With DRM and laws to criminalize circumvention of DRM in place, our culture gets locked down even more. It becomes technically increasingly difficult (and simply illegal) to use many of our cultural products, like pop music or election campaign footage, to create something new. We live increasingly in a permission culture, where new creators have to ask the powerful or creators from the past for permission, rather than in a free culture that would uphold the individual freedom to create. At the same time, while digital technology would allow us for the first time in history to build a library accessible to everyone, larger than the Library of Alexandria, we run the risk of forgetting history as past culture is locked down by law and DRM. While you theoretically still could sometimes make legal use of such material under the terms of fair use, and fight for your right to do so in court, this is no longer possible if law is interpreted by your computer rather than a judge. If the footage of the landing on the moon had been broadcasted with DRM in place, you couldn’t reuse one second of the clip, regardless if legal under fair-use or not—because your DRM-crippled computer prevented you from doing so.

Conclusion

We live in a time where digital technology enables individuals to produce and distribute creative works more easily and cheaply, rearrange old footage to tell new stories or cite from the past, effectively creating and shaping more of their own culture. These practices are increasingly hindered by the old industry that is threatened with losing its monopoly on producing the lion’s share of our cultural production. Wrapped up, the changes we have seen recently in law, technology and in the concentration of the media market lead to a devastating conclusion: There has never been a time in history when more of our “culture” was as “owned” as it is now. And yet there has never been a time when the concentration of power to control the uses of culture has been as unquestioningly accepted as it is now. (Lawrence Lessig [13])

Bibliography

1(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_market), Wikipedia

[2] Client programs for various peer-to-peer networks that are free software: eMule, MLDonkey, Gnucleus (Windows only) or LimeWire

[3] Some free software BitTorrent clients: Azureus, BitTornado or Transmission

4(http://www.downhillbattle.org/reasons/), Downhill Battle

[5] Various proposals summed up: Making P2P Pay Artists, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF); and an outlined proposal: A Better Way Forward: Voluntary Collective Licensing of Music File Sharing, EFF

6(http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/3140160.stm), BBC News;RIAA sues computer-less family, Ars Technica;“I sue dead people...”, Ars Technica

7(http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070625-exonerated-defendant-sues-riaa-for-malicious-prosecution.html), Ars Technica

8(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concentration_of_media_ownership), Wikipedia

9(http://arstechnica.com/articles/culture/drmhacks.ars), Ars Technica

10(http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070121-8665.html), Ars Technica; Why you should boycott Blu-ray and HD-DVD, Blu-Ray Sucks

11(http://www.macworld.co.uk/news/index.cfm?NewsID=14495), Macworld; iTunes and Digital Downloads: An Analysis (continued), Future of Music Coalition

12(http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070115-8616.html), Ars Technica

[13] Lawrence Lessig: Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity, 2004, p. 28