We all know that the typesetting of Free Software Magazine is entirely TeX-based. Maybe somebody don’t know yet that Prof. Donald Knuth designed TeX, and did it about 30 years ago. Since then the TeX project has generated a lot of related tools (i.e., LaTeX, ConTeXt, , and others).

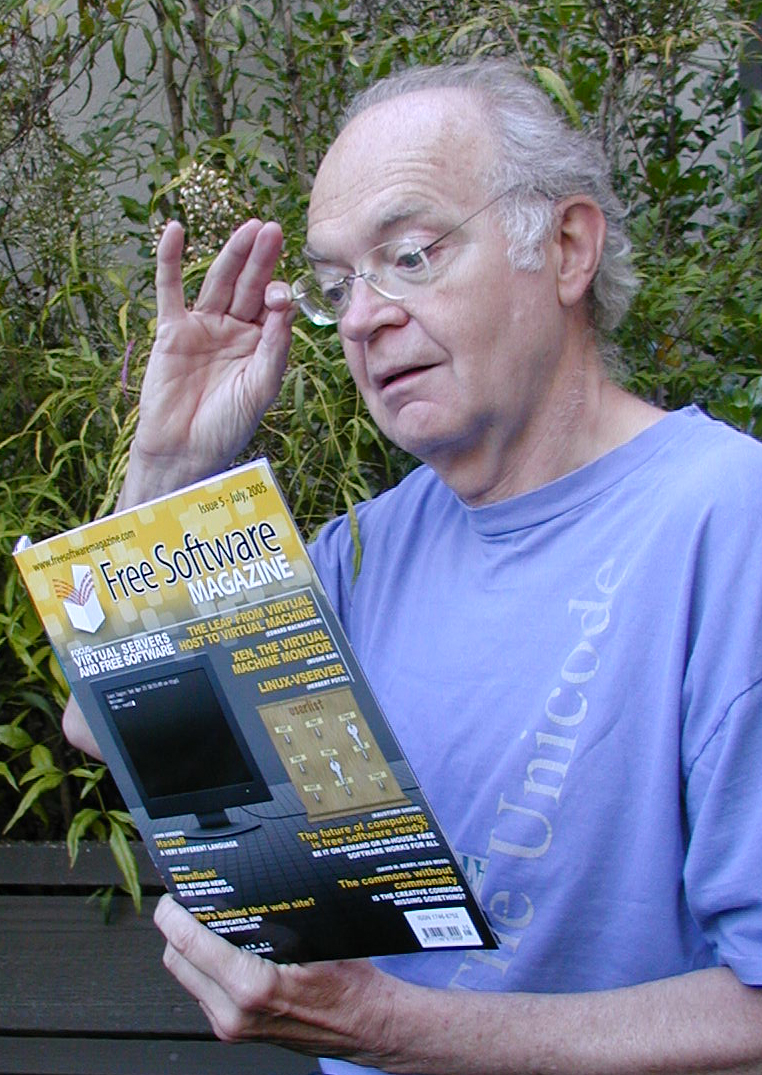

This year I had the chance and the honor of interviewing Professor Knuth. I’m proud, as a journalist and FSM’s TeX-nician, to see it published in what I consider “my magazine”.

Donald E. Knuth, Professor Emeritus of the Art of Computer Programming, Professor of (Concrete) Mathematics, creator of TeX and METAFONT, author of several fantastic books (such as Computers and Typesetting, The Art of Computer Programming, Concrete Mathematics) and articles, recipient of the Turing Award, Kyoto Prize, and other important awards; fellow of the Royal Society (I could keep going). Is there anything you feel you have wanted to master and haven’t? If so, why?

Thanks for your kind words, but really I’m constantly trying to learn new things in hopes that I can then help teach them to others. I also wish I was able to understand non-English languages without so much difficulty; I’m often limited by my linguistic incompetence, and I want to understand people from other cultures and other eras.

Your algorithms are well known and well documented (I’ll only quote, for brevity’s sake, the Knuth-Morris-Pratt String Matching algorithm), which allows everyone to use, study and improve upon them freely. If it wasn’t clear through your actions, in an interview with Dr. Dobb’s Journal, you stated your opinion about software patents, which are forcing people to pay fees if they either want to use or modify patented algorithms. Has your opinion on software patents changed or strengthened? If so, how? And how do you view the EU parliament’s wishes to adopt software patent laws?

I mention patents in several parts of The Art of Computer Programming. For example, when discussing one of the first sorting methods to be patented, I say this:

Alas, we have reached the end of the era when the joy of discovering a new algorithm was satisfaction enough! Fortunately the oscillating sort isn’t especially good; let’s hope that community-minded folks who invent the best algorithms continue to make their ideas freely available.

I don’t have time to follow current developments in the patent scene; but I fear that things continue to get worse. I don’t think I would have been able to create TeX if the present climate had existed in the 1970s.

On my recent trip to Europe, people told me that the EU had wisely decided not to issue software patents. But a day or two before I left, somebody said the politicians in Brussels had suddenly reversed that decision. I hope that isn’t true, because I think today’s patent policies stifle innovation.

However, I am by no means an expert on such things; I’m just a scientist who writes about programming.

So far you have written three volumes of The Art of Computer Programming, are working on the fourth, are hoping to finish the fifth volume by 2010, and still plan to write volumes six and seven. Apart from the Selected papers series, are there any other topics you feel you should write essays on, but haven’t got time for? If so, can you summarize what subject you would write on?

I’m making slow but steady progress on volumes 4 and 5. I also have many notes for volumes 6 and 7, but those books deal with less fundamental topics and I might find that there is little need for those books when I get to that point.

I fear about 20 years of work are needed before I can bring TAOCP to a successful conclusion; and I’m 67 years old now; so I fondly hope that I will remain healthy and able to do a good job even as I get older and more decrepit. Thankfully, at the moment I feel as good as ever.

If I have time for anything else I would like to compose some music. Of course I don’t know if that would be successful; I would keep it to myself if it isn’t any good. Still, I get an urge every once in awhile to try, and computers are making such things easier.

There are rumours that you started the TeX project because you were tired of seeing your manuscripts mistreated by the American Mathematical Society. At the same time, you stated that you created it after seeing the proofs of your book The Art of Computer Programming. Please, tell our readers briefly what made you decide to start the project, which tools you used, and how many people you had at the core of the TeX team.

No, the math societies weren’t to blame for the sorry state of typography in 1975. It was the fact that the printing industry had switched to new methods, and the new methods were designed to be fine for magazines and newspapers and novels but not for science. Scientists didn’t have any economic clout, so nobody cared if our books and papers looked good or bad.

I tell the whole story in Chapter 1 of my book Digital Typography, which of course is a book I hope everybody will read and enjoy.

The tools I used were home grown and became known as Literate Programming. I am enormously biased about Literate Programming, which is surely the greatest thing since sliced bread. I continue to use it to write programs almost every day, and it helps me get efficient, robust, maintainable code much more successfully than any other way I know. Of course, I realize that other people might find other approaches more to their liking; but wow, I love the tools I’ve got now. I couldn’t have written difficult programs like the MMIX meta-simulator at all if I hadn’t had Literate Programming; the task would have been too difficult.

At the core of the TeX team I had assistants who read the code I wrote, and who prepared printer drivers and interfaces and ported to other systems. I had two students who invented algorithms for hyphenation and line breaking. And I had many dozens of volunteers who met every Friday for several hours to help me make decisions. But I wrote every line of code myself.

Chapter 10 of my book Literate Programming explains why I think a first-generation project like this would have flopped if I had tried to delegate the work.

Maybe you feel that some of today’s technologies are still unsatisfactory. If you weren’t busy writing your masterpieces, what technology would you try to revolutionize and in what way?

Well certainly I would try to work for world peace and justice. I tend to think of myself as a citizen of the world; I am pleasantly excited when I see the world getting smaller and people of different cultures working together and respecting their differences. Conversely I am distressed when I learn about deep-seated hatred or when I see people exploiting others or shoving them around pre-emptively.

In what way could the desired revolution come about? Who knows… but I suspect that “Engineers Without Borders” are closer than anybody else to a working strategy by which geeks like me could help.

Thank you again for your precious time.

Thank you for posing excellent questions!