In lieu of today's regular column, I've decided to present an edited transcript of a very informative interview of Nina Paley by Thomas Gideon of "The Commandline Podcast." Paley has been doing a lot of interviews since her free-licensed release of "Sita Sings the Blues" and her subsequent work with QuestionCopyright.org (specifically her two "Minute Meme" animations: "Copying Is Not Theft" and "All Creative Work is Derivative") -- reading them all would be quite a bit of work. But this interview is possibly the best -- covering all of the major issues she's been talking about in what I thought was a very insightful way. So: kudos to Nina Paley and to her interviewer, Thomas Gideon, and I hope you find this text version interesting.

The original podcast, posted on February 24, 2010, can be found at The Command Line. Unfortunately, as Gideon notes in his introduction, the audio quality on Nina Paley's voice was very poor due to an analog phone line (which is one of the reasons why I wanted to transcribe the interview). Here I have also edited the interview down just a bit for clarity. I believe it is an accurate representation of "what they wanted to say." I've also, of course, added links and illustrations for the topics mentioned in the interview. Be aware, this column is considerably longer than usual, but I wanted to include the entire interview, because I think anyone interested in the future of free culture (including free software) would benefit from reading it.

"Because she is not granting any one distributor exclusive rights, she is avoiding that monopoly aspect of contracting her rights away to a distributor"

Nina Paley is a cartoonist and animator who in recent years discovered the serious faults of our long-standing copyright and licensing system through her experiences in making and releasing "Sita Sings the Blues." After considerable trouble involved in fulfilling all of the licensing obligations for the film, she became a serious advocate for both free culture and copyright reform (or abolition), allying herself with QuestionCopyright.org. Her current project -- recently funded -- has been to produce "Minute Memes." These are short animated films which promote free culture ways of thinking about copyright, specifically intended to counter propaganda from industry copyright maximalists like the MPAA and the RIAA.

In Gideon's introduction, he also mentions a little bit of information about Paley's talk at American University, which was given shortly after his interview was recorded:

The other thing I wanted to mention is that I also just had the privilege of seeing her talk live in-person at American University. And I was very thrilled that she expanded on one of the things that we touched upon in this interview: That is the kind of barrier that copyright as an actual economic monopoly presents -- talking about how there cannot be a real "market value" for a copyrighted work because of the monopoly aspect.

And also that, in working with the distributors [...] that, because she is sharing freely, because she is not granting any one distributor exclusive rights, she is avoiding that monopoly aspect of contracting her rights away to a distributor. As she put it, if one distributor "sleeps on the job," then she can still work with other distributors who are more competitive, enabling more of the competitive aspect that we expect when we talk about market economics.

He also mentioned something I think is worth quoting about Nina Paley, which I have been very grateful for myself, which is that she's been very open about the economics of her marketing and distribution effort. This kind of openness is certainly an unusual thing to find in any competitive enterprise, where deals and salaries are frequently kept secret to avoid tipping off the competition. Perhaps this reflects the openness of her film release itself or perhaps it is simply her "gift" to the free culture community, but whatever has motivated her, it has been extremely valuable and I believe, will be even more valuable as a guide to others who want to make free-licensing successful and perhaps someday soon become the new norm for releasing films and other works of art.

So, without further ado...

Thomas Gideon's interview with Nina Paley

Q. Nina Paley is a cartoonist, an animator, and most recently, a free-culture activist. On her website, she describes herself as "America's best loved unknown cartoonist." Her most recent work, "Sita Sings the Blues" may be her most well-known thanks to her open sharing of the work in progress and the issues surrounding her clearance and use of songs performed by Annette Hanshaw.

Welcome to the show, Nina!

A. Hello!

Q. When you selected the first Hanshaw song, "Mean to Me," for the original short "Trial By Fire," did you have any inkling of what was to come? Or was this really the first time you had to navigate such a minefield of rights and clearances?

A. This was certainly the biggest minefield I ever navigated, but I did have an inkling in that I knew that it was dangerous, and I had never done it before -- and I had heard people warning me to just not use the songs at all.

So I knew that I was in for some sort of adventure. But I was focusing on making the work.

I certainly spent some time at the beginning considering not making it at all, which would've been the safer thing to do, but if I had done that then the "terrorists would've already won" and it was so important to me to make this work that I just put that at the forefront and figured... any problems that come up I'll do my best to deal with them, but it's not worth not creating art, it's not worth killing a piece of art before it's even made just because I am afraid. So I went ahead with it.

"This was certainly the biggest minefield I ever navigated"

Q. Is it that artistic expression that drove you forward? Or was it the emotional component that surrounded the need for you to tell this story? Or what was it that drove you through that to take that risk rather than just not do it?

A. Well, those are related. My emotional needs are very much related to my art-making. And this particular work was a pretty direct expression of my thoughts and feelings and state of mind, and I felt a pretty profound need to express those things as best I could. I wanted to be heard and I wanted the story told, and... It gets kind of mystical: I was "ordered by my Muse" to do this.

Certainly I tried other things.

It's a lot of work. When I'm inspired, initially I'll realize that this could be an incredible amount of work, and I'll resist committing to it... and see if there's any other way to do something. The first thing I check if I'm inspired is "does this already exist" -- because if it already exists, I don't have to make it again! And I did look, and I didn't see this work existing. I just felt this really profound need to make it exist. Whether that is because I needed the therapy or for some other reason I can't really say, but the compulsion was very strong.

Q. In going back and kind of reviewing some of your earlier animations and looking at your cartooning, "Sita" seemed very consistent to me in that it seemed very personal. It did seem very candid and direct. Did you draw any strength from those past experiences in any artistic or emotional similarities in them?

A. Past experiences with my comic strip?

Q. Well with "Pandorama" and "Fetch"... and I know there was some interesting "discussion," shall we say, around "Stork." [Editor's note: I don't know what "discussion" he's referring to, but these films are in the NinaVision collection of short animations that I've mentioned in previous columns]

A. Oh! Yeah, well, certainly making short films led to my making this feature film. I don't think I would've made a feature film out of thin air, but that's not to say that someone else won't.

I mean I've learned from everything I've done, every piece of art I've done, including the comics. And I guess because of that, I felt that I was capable of making this film. And I should say that it's not like I wanted to make a feature film. I've met a lot of short-film makers where to them the short film is a stepping stone to the feature film, and I never felt that way. I never had these aspirations of being a feature filmmaker. And in fact I still don't: it's not like, 'now that I've made a feature film, I'm going to make another feature film and another and another....'

It's just that this particular story was best told as a feature film. That seemed to be the form that it was coming out as. Initially I thought it would come out in another form. Initially I thought maybe a comic book, or maybe well, a short film -- I made it as a short film hoping that that would take care of it, that would take care of the compulsion and satisfy my muse. But it didn't, I had to make something bigger.

"I made it as a short film hoping that that would take care of it, that would take care of the compulsion and satisfy my muse. But it didn't, I had to make something bigger."

Q. I understand. And again, in looking back especially at your earlier films, that would seem more consistent: that you were either experimenting with medium or you were experimenting with story telling -- in ways that I found compelling in watching them, but they definitely felt more experimental. So I can see kind of that rationale of just experimenting with "Trial By Fire," and seeing if that was enough to 'scratch that itch.'

A. Yeah, well, actually the whole feature film was an experiment as well. I mean, the narrators (which many people liked the most, their favorite part of the film) -- that was pure experiment. The film needed something, and so I asked these friends of mine if they would come into the recording studio and let me interview them. And it was unscripted, I didn't know what I was going to do with the resulting audio, but it was great! And I edited it and used it. But that came about in a sort of serendipitous experimental way, I just was guided by knowing that it needed something, and 'let's try this, maybe this will work' -- and it did.

Q. I do have to ask one question about "Sita" and your artistic and technical thinking -- on behalf of a friend of mine, who finally watched the film after I had been talking about it for awhile, and was kind of taken aback by one of your portrayals of Sita. I think you know the one I'm getting at, the really exaggerated, kind of highly stylized... Have you had people question you about that, have you had kind of more charged conversations come up over this sort of overly feminized version of the character?

A. You're putting it so delicately! What's bothering them is the big breasts. She has big breasts.

Yeah, and I do occasionally get people.... I've presented it to groups of students, and once or twice there's been a woman who's sort of objected to this portrayal of Sita: that she's too sexy.

Which is odd to me, because I cannot imagine someone finding that portrayal erotic. For me, it's.... Well there are two reasons for that portrayal -- one is that over and over again she's presented in the text as the ideal woman, and in the text she's super, super hot. So, you know, both this crazy attractiveness of her and the ideal woman thing -- I created this "ideal woman" shape. Same thing with Rama in those sequences. Like if you were to extract purely the most feminine/female attributes and the most masculine/male attributes, that's what I put into that depiction of Sita and Rama.

But the other reason I did it, and I think the more profound reason I did it, is that Sita's sexiness is her burden, she's obviously pure, she's obviously completely devoted to Rama, the narrative points that out. But her sexiness drives the narrative. It's why Ravana lusts after her, and it's why Rama doesn't trust her. And it creates a lot of drama and creates a lot of suffering and burden for Sita, so, even though she's obviously pure...

I mean just because she's the 'most beautiful woman in the world' or the 'ideal woman' or any of those things, that doesn't affect her purity. That's sort of the point of the story: regardless of what she looks like, she has a very pure character and she's completely devoted to Rama, and such is true in my film as well.

So, I sometimes think that when people object to that depiction of her, that they're kind of buying into this idea that you cannot both be hot and have integrity.

Q. What I find fascinating of the portrayal, and I think what struck me more than falling for that trap, was the energy of that particular style. When the narrative shifts over to that version of the characters, it has this sort of zany "Fleischer" kind of feel too it, where everybody's kind of bouncing. That's when the torch songs come in, and you get more of that heartfelt emotion. And I found a sort of innocence in how they're acting -- that it's not as textured as the more painterly renditions of the characters. So yeah, I'm mystified, but maybe for different reasons. So I'm very glad to hear you dig out that little bit of profundity there.

A. I wish I could say more about it. People ask me about the styles all the time, [but] you know one of the reasons I used these different styles was to give a little teeny taste of the breadth of Ramayana art that's out there... and also to keep myself from being bored. But really they just came to me. I mean I made the film by feel, and I just picked things that felt right. There wasn't a real formula to the whole thing. And again the whole thing was an experiment, so I was just doing what needs to be done one thing at a time.

"As I was going through the process of clearing the rights, realizing how broken the copyright system is, I wanted to do something."

Q. Another aspect of the film, and what you're doing around it, that I find fascinating, is that you went into debt for the copyright clearances. So you're trying to recoup some of that debt. Obviously from the comments you made at World's Fair Use Day, you're artistic, but you're also interested in supporting your ability to continue creating that art. Is that informed by that same sort of spirit of experimentation as well?

A. Well sure. As I was going through the process of clearing the rights, realizing how broken the copyright system is, I wanted to do something. And so I thought 'Hey, I have this feature film and all this critical praise -- all this attention, it seems like I could something with this.' Now I've figured out how to do something with it: it's just to show it, to actually put it out under a copyleft license.

And that is a pretty grand experiment, and it has exceeded my expectations.

Probably it hasn't exceeded Karl Fogel's expectations, because Karl Fogel (who's with QuestionCopyright.org) has already released two books under open licenses, and he works with free software. But for me, this was a very new thing to do.

"In a way anything that is released now is in a unique situation, because a society and distribution is changing so quickly. People are getting more and more empowered via the internet to share and distribute works."

Q. Do you think that your experiment is something that other people can draw upon that maybe we can generalize and draw some lessons from? Or do you think that it's exceptional? For a lot people who do what you do, the criticism comes back that: 'Sure it worked for Nina, it worked for Cory, it worked for Trent, it worked for individuals....'

But do you think there's something there that's not just your experiment, but something that might be hinting at new models that anybody could utilize to do something similar?

A. Of course I think that other people could utilize this model.

But I also acknowledge that things are changing. I don't agree that this is a secret unique situation just for my film. But in a way anything that is released now is in a unique situation, because a society and distribution is changing so quickly. People are getting more and more empowered via the internet to share and distribute works. Right now there are things about Sita's release that I imagine will change.

For example, people are used to being harassed by publishers, they're used to being harassed by distributors, and they're used to being disrespected by them. So that I am enjoying a very high level of good will -- just plain old gratitude from a lot of viewers. Who are like "Oh wow, she actually respects us. Thank you!" It's just so unusual right now to not abuse your audience!

And yeah, I think in the future, people will expect not to be abused, and it won't be this big deal for not abusing your audience.

"People are used to being harassed by publishers, they're used to being harassed by distributors, and they're used to being disrespected by them. So that I am enjoying a very high level of good will."

I also think that right now we're in this transitional time where people have been forced to pay for inflated prices for copies but those prices won't be very realistic in the future. So right now people typically have to pay $25 to buy a DVD, and they're sort of accustomed to that, so when I charge $20 for my DVD, lots of people pay that. But I don't know how sustainable that kind of pricing is going to be. I really don't know.

In the case of "Sita Sings the Blues": unfortunately copies that are sold, have to be priced kind of high, because each copy has a flat amount that I have to pay these corporations that control the old song licenses. So whether a copy is sold for 50 cents, or $10, or $20, whatever it is, I have to pay about $1.85 to make that legal per unit. That introduces a lot of price inflexibility. But for other films... you know hopefully in the future, there won't be as bad licensing structures, and prices can actually adjust closer to what the copies are actually worth.

Q. But you're not relying solely on the copies -- I watched a video of talk of yours, where you were talking about giving away copies, you know, kind of routing around that cost you were talking about, and then...

A. Well I'm not giving away copies. People are free to make their own copies. There's a big difference between giving away copies and, and not punishing people for making their own copies. I don't freely give away copies of the DVD. Like I say, those cost me money to make, and they're a real hassle for me to make. But it's absolutely no hassle for me for someone else to make a copy -- or several copies.

"It was actually Karl Fogel who developed something initially called the 'author endorsed' mark, but we changed to 'creator endorsed' mark."

Q. But my point is that you do have this cost, the Question Copyright page has your progress to date and shows that the donations that you receive are being used directly to pay down that debt that you undertook. But you're also selling merchandise. You worked with them to come up with this very clever kind of mark of authenticity, so you're not relying on just that one mode, you're kind of firing on multiple cylinders trying to support yourself with this.

A. Yes. I mean there are various ways that money comes in. There's donations, there's sales of DVDs and other ancillary merchandise (because in our case the DVD is ancillary merchandise) at the "Sita Sings the Blues Merchandise Empire" which you can find online at http://sitasingstheblues.com/store -- and those include T-shirts, and cloisonné pins and necklaces, and I don't know, we've got stuff. 'Stuff for sale'... 'Scarce tangible goods' for sale.

Q. I'll include a link to the store in the show notes. But it's not just that. It's that you experimented with this notion that you're not excluding other people from say, putting your designs on their own stuff. If they want to go to Cafe Press or Zazzle or something like that, you're fine with that.

But you've come up with this positive way of addressing this with a positive mark that says "if you want to support Nina Paley, the creator" then you look for this mark, and that says that that's a good, authorized-by-you product (whether you're producing it or you're partnering with someone to produce it), so that people who want to purchase those goods out of a sense of fairness, or out of a sense of supporting you as an artist, have that signal to follow.

A. Yes. It was actually Karl Fogel who developed something initially called the "author endorsed" mark, but we changed to "creator endorsed" mark. Now I think maybe we should've called it "author endorsed" mark after all, but oh well.... And yeah, it does exactly that.

It has another benefit as well: of simply separating endorsement from copyright. When I was at World's Fair Use Day, I talked to many people -- I heard about these cases where musicians would sue somebody who legitimately licensed their work [and] had used the work -- because they didn't want to be seen as endorsing it... usually a political viewpoint that they didn't endorse. And it's so assumed that the rights to something go along with the artist's endorsement. And it's so not true!

I mean there's a whole market of buying and selling rights to musical works that have nothing to do with the artists' endorsement. It's ironic that so many artists complain about this and then try to use copyright to sue, as though copyright has anything to do with their endorsement and it really doesn't. Copyright in their case has to do with money.

I guess I'm thinking about the sort of ... oh that musician, who was it, come on brain...

Q. Was it Jackson Browne, with...?

A. It was Jackson Browne, yes, and that Republican ad.

"I heard about these cases where musicians would sue somebody who legitimately licensed their work and had used the work -- because they didn't want to be seen as endorsing it... It's so assumed that the rights to something go along with the artist's endorsement. And it's so not true!"

Q. And you're right, the only recourse he had was a copyright complaint and that wasn't really what was at issue. What was at issue, if I'm recalling this correctly, was that he didn't agree with McCain's politics and didn't want his song associated with the campaign.

A. Right. And they licensed it fair and square. You know, he'd turned it into a commodity, and they bought it. You can't treat your work like a commodity and then complain about this.

But you can separate out your endorsement, which is what I've done. So, I know that people are going to be doing all kinds of things with "Sita Sings the Blues" -- they already are -- and people say, 'well, what if somebody makes some remix you don't like?' I don't care, because people know that my endorsement isn't implied in any remix at all.

I have to let people say what they're going to say with it and do what they're going to do. I can't control other people. But I can control, to some extent, my explicit endorsement.

Q. I'm glad to hear you explain that, because in reading Karl's write-up of this, that aspect of it just didn't come out. It certainly makes sense, and it gives a good strong incentive for a creator to use the mark beyond just the commoditization. That's pretty cool.

A. Yeah, well that comes up over and over again with artists. They're so worried that their words are going to be twisted around, and people are going to think that they said things that they didn't say.

I don't feel that way at all with "Sita Sings the Blues" because it's so well known that it's free, and I would love it if we lived in a world where these things just weren't associated at all -- where people knew the difference between an artist endorsement and quoting them.

Q. Sure.

I wanted to switch from there to -- still in the same vein of experimentation -- some of the work you're doing with Karl Fogel at Question Copyright: the Minute Memes. These are a series of short videos highly suitable, and packaged for viral sharing, meant to act as seeds of conversation. The first was "Copying is Not Theft" and the second just came out last week, "All Creative Work is Derivative". What is your sense of how well these are succeeding so far at that stated goal?

A. I don't know. Right now we only really have one-and-a-half of them, because "Copying is Not Theft" is not really done yet. I released it with a scratch track, and hoped that somebody would provide the perfect soundtrack for it, and it hasn't quite happened yet. When it does happen, we'll make another big push with it. And actually Nik Phelps, who is a musician I collaborated with a lot in San Francisco (he now lives in Belgium)... he's working on a version. Hopefully that will satisfy us.

That said, there are some really fantastic remixes. They're just not quite what we imagined the official ones to be. My favorite is the punk remix. And somebody recently did a French version which is adorable -- the voices of the bunnies are absolutely perfect! -- but it's in French.

Copying Is Not Theft

Punk version:

French version with the cute bunnies:

here's a whole lot of 'not theft' of this meme going on at YouTube. Which could be seen as performance art, really...

Q. Well, you know copyright's still something we want to educate people about in France, there's nothing wrong with that!

A. Oh my God, yes, truly necessary right now in France. France is kind of a disaster when it comes to copyright, but there's also a "French Resistance."

"Copier n'est pas Voler" is how it is being shared there. People can share my film in France too, but actually don't even get me started about France. I have a French distributer, but it's very unfortunate, the laws in France... but anyway, I was saying....

We have like one and a half minute memes. So the first truly finished Minute Meme was the one I released last week, which is "All Creative Work is Derivative." On our own, so far, it's just spreading virally. Everyday more people share it with more people. Hopefully, eventually everybody in the entire world will see it. But right now, I think we're between 5 and 6 thousand.

Q. Well I hope so. Because one of the things that struck me, was I mean first the Todd Michaelsen song, "Sita In Space" is that right?

A. No, that one is called "Sita's String Theory."

Q. Well I love all of the tracks that Todd has released so far for sale. But "Sita String Theory" and the animation that you've crafted to go along with this is so striking in itself.

But beyond that, we've talked about how you experiment and iterate you way through these and this seems to be another example. A lot of what you seem to be doing at Question Copyright is kind of transparent and in the open. Do you think that people will get pulled into that as well, or just see the stand-alone finished work, or maybe a little of both?

"I actually like 'All Creative Work is Derivative' because I think it's a successful piece of art in that it works on a sub-verbal level -- that the concept comes across and it doesn't need the words to come across."

A. I'm not expecting people to get pulled into Question Copyright. They're called "Minute Memes." We put some things out in the world that point out that sharing is super-important, and I actually like "All Creative Work is Derivative" because I think it's a successful piece of art in that it works on a sub-verbal level -- that the concept comes across and it doesn't need the words to come across. It comes across better than words. And I just want the concept in circulation more. They'll affect people on whatever level.

I don't mean "affect people" -- it's really a conversation. It's not like this is going to control anybody's mind. But hopefully, it will give people tools to think, which any language does. Any kind of art or cultural work does that. But no, I don't expect it to turn everyone into copyright reform theorists.

Q. But if it raises consciousness, if they think to ask a question, to enter that conversation about 'Is this right?', 'Could I do something else?', 'Is there something else out there?'.... They don't necessarily have to be an activist, but if they're a bit more engaged, rather than accepting this norm of 'permission for everything' when there are other things out there...

A. Yeah, well I'm hoping that when people come to forks in their road, where they have to make a decision about what they're doing or they're in a conversation where somebody does say "This is stealing" or "That person stole that" then maybe they'll think "Hmm, I'm not so sure that is stealing" or if they have a choice in their own work, 'Should I include this piece of information in this communication I'm doing?', 'Would that be stealing?' Then hopefully they'll remember this little video that they saw, and have that affect their decision-making process. Where before they would have nothing to draw upon except propaganda from the MPAA that says 'Downloading is stealing' or propaganda from whatever copyright coalition that told you 'Everything you do is stealing,' maybe they'll....

I don't know, I don't know what's going to happen, it just feels right.

Q. Well, I think you captured it. I think it is a hope that they won't just give into the propaganda. It will stick with them, and it will give them pause, whether they go to any of the much deeper resources, or if they just have that moment of pause, "Maybe something isn't right here."

A. Yeah. Memes are cool, you know, but they go in there, and you don't know what they're going to do once they're living in other minds.

Q. But then you've also got all of the people who are building things like the EFF, or the Creative Commons, or like what Karl Fogel's doing with Question Copyright, who can use these as tools as well.

Hopefully with that idea of them being "memes", they do take on a life of their own, they spread virally from mind to mind -- but other people can use them intentionally.

You use the word "propaganda" when you talk about the copyright alliance, but "propaganda" doesn't have to be such a dirty word that we avoid using these as tools for communication too to say "Hey...." Maybe not to club people over the head, but to intentionally use them to start those conversations.

So they probably serve multiple purposes, is what I'm getting at.

A. I will say that with "All Creative Work is Derivative," the Muse took over at a certain point. I started with a message I was hoping to convey. But as I got into it, it really just became its own thing: I really wanted to see -- 'is it possible to create animation where every frame was a different piece of art?' I was excited purely by that idea, which came along as I was trying to express this other idea, and that's what really took over.

Q. Well, I think that shows through. I mean it really does. It's the music; it's the quality of the work; and it is that realization about part-way through when you do realize that's what's going on here -- that every pose is something different. Yet somehow you've welded this into a seamless whole that has that "catchy", "sticky" sort of quality that you want in a good piece of memetic video like that.

A. Well thanks!

But anyway, I mention that, because something happened when I was working on that piece, in that, even though it has a message tacked on at the end, that piece I will say is really art. I mean I like to think that everything I do is art. But you know, "Copying Is Not Theft" was more of a straight propaganda job. But this one leads somewhere else.

Q. Well, you have plenty of ideas to explore. I saw the update on the site that the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts has given you a grant, so at least the first three are being supported through that. Hopefully you'll find other ways of supporting at least the original twelve.

I'm very much looking forward to seeing what you guys do with "How Artists Really Make Their Livings" and "Strangers in the Street Explain Copyright" with a lot of discussion around "folk copyright" and "paracopyright" for the individual versus for corporations.

In a lot of the speaking and activism that I do with all the misunderstandings and misperceptions of copyright, it'd be useful to have a tool like that to say "You're not alone and there are good questions to ask" -- and maybe then seek out some resources for answers. So, hopefully you get further along, and you can pursue both the art and the message.

How many do you have now? It says twelve, and you've received submissions.

"A really important one for me to make is distinguishing between copying and plagiarism"

A. These are just ideas: we just thought of what we thought and put them in a list. I don't know how many of these will actually get made. A really important one for me to make is distinguishing between copying and plagiarism.

Because that's usually the first thing that goes up -- people have conflated them. And I have yet to receive muse guidance on this one. I'm not sure how I'm going to tackle it. There's a lot of different ways to do it. Maybe I'll just state the obvious, since it seems so obvious that copying something is not the same as plagiarizing it. But I want to make it entertaining and sticky.

Q. So many free culture folks and other activists besides have discussed the need for carving out limits and exceptions around non-commercial uses. Public Knowledge -- who hosted World's Fair Use Day where we actually got a chance to meet and talk -- just released their "Copyright Reform Act" this five-point model for reforming copyright, with a special focus on balancing fair use.

But you seemed definite on this, that "Sita" is not fair use -- you had to pay to clear the torch songs that you used. And there are many commercial aspects besides: you talk about selling the containers and the costs involved in doing that.

And I was actually very intrigued at that event with your dissatisfaction at some of the other creators looking at "fair use" as if that were the only answer. Do you think that there is a strong case to be made for reforming or augmenting commercial copyright to encourage more uses beyond what we just traditionally think of as "fair use"?

A. Yeah, I think people are very confused about what "commercial" means. A lot of artists seem to be against "commercial use."

The funny thing about "non-commercial" licenses, actually, is they are exactly what corporations would want you to use. What a "non-commercial" license does is, it says 'You can't use this commercially except with permission.' And they love that, it just perpetuates commercial culture, and what it ensures is that anybody who doesn't have a lot of money to pay you off won't be able to use your work.

"The funny thing about 'non-commercial' licenses, actually, is they are exactly what corporations would want you to use."

So once again, it gives corporate entities a lot more power than just ordinary people who might want to -- oh say -- be paid for their creative work. That would be nice!

The "Non-Commercial" Creative Commons licenses actually are pretty pernicious because they basically lock out exactly the kind of people you want to be collaborating with.

And there's a very widespread hatred of "commercial activity," a kind of hatred of commerce, and that's very misplaced. The problem isn't commerce, the problem is monopolies. And people are so used to commercial entities having monopolies and then using these monopolies to screw up other people and lock people out and abuse citizens, that they think that by making things "Non-Commercial" you're going to solve that problem. But actually the problem is monopolies. That's something I need to turn into a Minute Meme: "The Problem is Monopolies" it's not commerce, it's monopolies.

Q. I agree. I think you do need to turn that into a Minute Meme. At the very least, we've got this, your thoughts on that. I think that's great. I hadn't thought about it that way, and you've given me something to go back and ponder, because I think the kind of licensor you characterize, that's how I've thought about "Non-Commercial," and you've definitely given me a question to consider, in terms of which better supports the freer reuse of the work. That's an interesting wrinkle I hadn't considered.

A. Yeah, and I've benefitted so much from allowing -- I don't even want to say "allowing" -- but, being friendly. I allow and encourage commercial use, but I prohibit monopolies. That's the point of the copyleft license. So... any sort of business model that relies on monopoly is not going to be able to commercially exploit "Sita Sings the Blues" because you can't have a monopoly on it.

"But anyone that doesn't rely on monopoly is welcome to 'exploit' it. And the result has been these fabulous uses that technically are commercial -- or even if they're not commercial yet, they have potential to be commercial -- that are just awesome!"

But anyone that doesn't rely on monopoly is welcome to "exploit" it. And the result has been these fabulous uses that technically are commercial -- or even if they're not commercial yet, they have potential to be commercial -- that are just awesome! Like the MonkeyLectric bicycle wheel which has an LED array that you can put on your bike wheel, and when the bike wheel spins, it turns it into a video screen. They used "Sita Sings the Blues" in developing this, and they can ship it with "Sita Sings the Blues" already programmed into it. And that's fine. That does not take away anything from me. Nobody's going to see a clip on a bicycle wheel and then say "I don't see the movie now, I've seen ten seconds on the bicycle wheel." But it is awesome, it honors the work on a bike wheel.

MonkeyLectric Bike Wheel Sita

Here's the bike wheel Paley is talking about. As the wheel spins, the LEDs trace out a field of view, and can play back video (though the conversion software must be pretty interesting!).

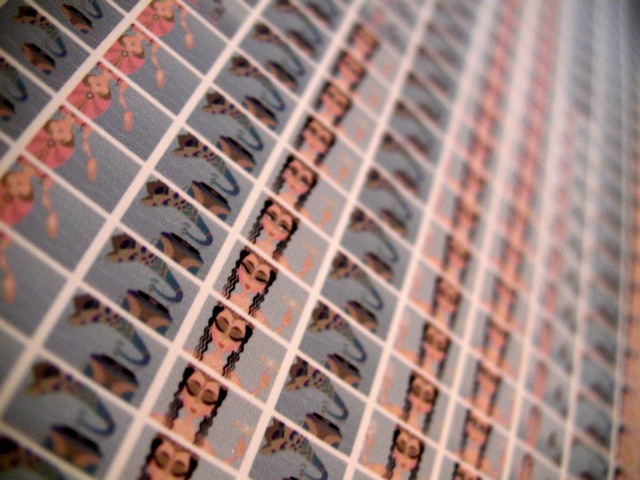

Also, Bill Cheswick, who's an engineer at AT&T came up with a really great way of printing posters that consist of every single frame of a film. Unfortunately, he can only test this if he has permission or if he can test with a film that has an open license, like "Sita Sings the Blues." And that has to include commercial use, because at some point he might want to sell these posters.

So, as a result, he's done these great experiments and development using "Sita Sings the Blues", and made these awesome posters of every single frame of "Sita Sings the Blues", and I think it would be awesome if he sold these things. I mean it would be more awesome if he could do any film, and I think it's ridiculous if he wouldn't be allowed to, like who's going to look at a poster with all these tiny half-inch frames of a film and go like "Well, I don't need to buy the DVD because I saw a poster," and yet that is what the law forces him to do.

So having the open license first, without needing to hear anything encouraged him to do the development with "Sita Sings the Blues." And of course he liked the results, and he contacted me, and now we know each other, and I have these posters, but it would've been fine even if we had never met each other.

"Who knows what other amazing things people are going to think of that we couldn't imagine, and those people need to be free to make money just like you and I need to be free to make money."

And that's... he's exactly the sort of person that I'm really happy to have working with my stuff. "My stuff" -- I mean it's not "my stuff" any more, but you know, it only helps me, it's only beneficial to me.

And I think of all these other filmmakers that have closed licenses on their films, and it's like 'Well, your stuff's not going to be on a bike wheel'; 'Your stuff's not going to be on these cool posters.' Who knows what other amazing things people are going to think of that we couldn't imagine, and those people need to be free to make money just like you and I need to be free to make money. So forget the "Non-Commercial" clause on it -- which is basically saying 'Yeah you can put it on the poster, but you can't sell it' or 'Yeah, you can put it on the bike wheel, but then you can't sell it' -- that's stupid.

Q. Even if I had questions left, I think I would have to go, because now you've instilled this deep burning desire for me to get these persistence-of-vision bike wheels with the monkeys from Sita in them. Do you have any upcoming projects that you wanted to promote before I let you go?

A. I forgot to mention that the official soundtrack has just been completed, and I just got a box of CDs yesterday, and the whole thing should be available online very, very soon. Like next week it should be available online.

And I will say, that you know I had to produce this CD, and my terms for producing it were that all the contemporary artists release their tracks under a ShareAlike license, and they did.

Q. Wow. That's fantastic. Great.

A. Yes, that's fantastic. We still hope that people buy it "normally," so we can give all that money to the living musicians. And it also has all the Annette Hanshaw tracks, and for those we have to pay license fees, but everything else that comes in goes to the living musicians.

Q. Okay. Well, thanks for the details on that, great.

A. Sure. Thank you!

Q. If you want to email me later on with some of the other speaking engagements, I'd be happy to publicize those as well and encourage people to come out and listen to what you have to say about your experiences as an entrepreneur and a creative. Thank you so much.

A. Thank you!

Licensing Notice

This work may be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, version 3.0. The original interview was conducted by Thomas Gideon with Nina Paley. This edited transcript was created by Terry Hancock for Free Software Magazine. Illustrations are under the same license and attribution, except as noted in their captions (all images in this article are CC By-SA 3.0 compatible).