Free software has many benefits: you can get more secure software, faster updates, lots of tutorials and, definitely, a new way of making software and software that builds communities. From this, the next logical step was Open Hardware.

Making Open Hardware possible

Free software is based in four main freedoms:

- freedom to execute programs

- freedom to access source code

- freedom to distribute copies

- freedom to improve and release that source code

Now, there are people talking about Open Hardware... Open Hardware? Is it a misspelling? Well, active projects like Arduino and SquidBee demonstrate that Open Hardware is a real and alive concept. But, what do these words mean exactly? Can you just use free software concepts and apply them to hardware?

First of all, it's important to understand that software and hardware belong to separate worlds. While software matters are usually ruled by copyright, hardware must be protected by patents. According to The U.S and European Copyright Office, copyright is a form of protection (...) granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Copyright protects original works of authorship including literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture, published or unpublished. It lasts 50-70 years after author's death, depending on specific country laws. On the other side, everyone who invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent.

There are also differences between the US, European and Japanese Patent Offices. The USPTO is the only one which is based on a first-to-invent system (instead of a first-to-file), meaning that a patent is granted to the person who first conceived and practiced the invention, rather than to the person who first filed the invention with authorities. There are some other differences, but the most important one in our case is that software patents are allowed in the US but not in Europe.

It would be difficult to explain how Open Hardware was born. Someone basically thought that an open computer was necessary in order to develop better drivers and write completely architecture adapted programs (http://www.openoem.com). In fact, there is an initiative called Open Hardware Certification program which (from the web site) is a self-certification program for hardware manufacturers. By certifying a hardware device as Open, the manufacturer makes a set of promises about the availability of documentation in order to program the device-driver interface of a specific hardware device. Enough documentation for the device must be available for a competent systems programmer to write a device-driver.

From another more philosophical point of view, you can find a free design for an active RFID device OpenBeacon, Open Hardware phones like TuxPhone and even an Open Hardware car called Oscar. All these projects will be released according to copyleft principles.

More and more Open Hardware projects can be discovered in Open Circuits, which provides a wiki to upload all kinds of useful information. These are just some examples which claim to be Open Hardware, although none of them define what that means.

Hardware is composed of several components e.g. firmware, schematics, circuit and layout diagrams, parts lists. Which components must be released to label a project as Open Hardware? If you look in depth at some Open Hardware projects you will find the Linksys router from WRT54G series. Its firmware has been released under GPL license, and the 3D printer RepRap has released most of its components. The Chumby project is made with free software and provides a HDK (hardware developer kit) with an special license that explains the terms under you can modify your chumby, but warns that by doing so you will lose any warranty.

Many projects claim to be Open Hardware, although none of them define what that exactly means

The challenges of releasing hardware

One of the goals of free software is that it can be accessed by everyone; but hardware has unavoidable costs for components and manufacturing. That’s why Richard Stallman, Free Software Foundation founder, said that getting Open Hardware wasn't as important as getting free software, since the hardware's copy and distribution process was more complicated.

Think about somebody in Italy who has made a program and decides to release it. Ten minutes later, somebody in Australia can download, compile and run that software; he or she even can contribute with improvements that the original author will enjoy next day. The only cost of this process is the Internet connection. If the same person in Italy designed an electronic circuit and released it, the only thing that our friend in Australia would be able to do in ten minutes is printing the schematic. Well, maybe he or she could manufacture a copy if the components were easy to get and owned the necessary tools. Another alternative would be ordering it from a factory, but this is expensive since hardware production is economically viable when ordering more than 1.000 units. Therefor, those who want to release hardware should design using common, cheap and standard components. Alteratively, if the project has global potential, reach a manufacturer agreement for producing a big batch at a low price.

If the same person in Italy designed an electronic circuit and released it, the only thing that our friend in Australia would be able to do in ten minutes is printing the schematic...

A practical example

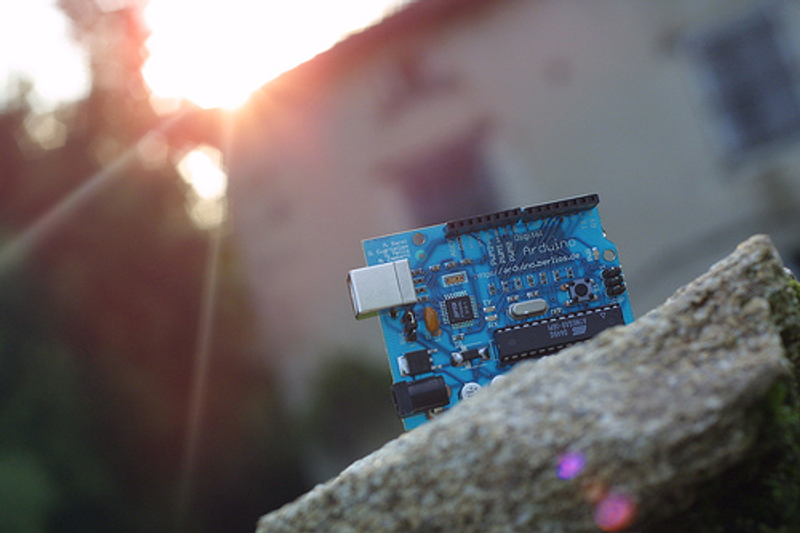

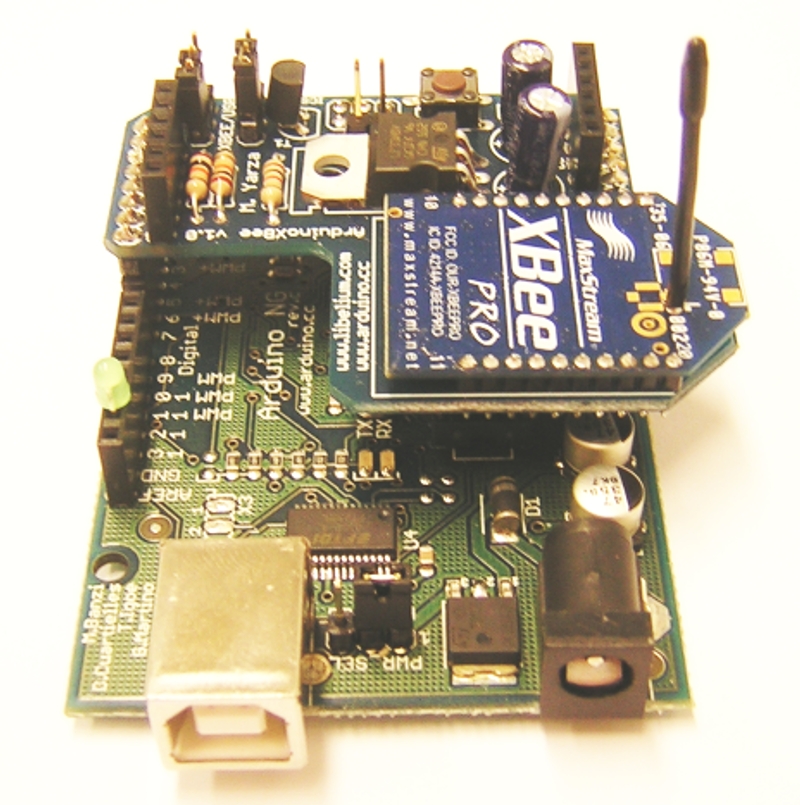

The Arduino prototyping platform is a good example of all this. It can be programmed to read sensors, control motors and build interactive objects and artistic installations. Its compiling environment is multiplatform and free (as in freedom) and the only extra hardware needed for programming it is a serial/ USB cable. This software can be downloaded from the website Arduino web site, which also contains Arduino schematics released under Creative Commons Attibution-ShareAlike. The project has used many ingredients to achieve a successful widely used project. For example, it contains a removable Atmega8 microcontroller which can be easily replaced if broken--without the need to buy a new Arduino board. Two years after its creation, you can see an expanding community of developers who support it, workshops all around the world, new plugins and modules like ArduinoXbee (ZigBee communications interface), Arduino BT (arduino with bluetooth connectivity), Arduino Mini or the recent Arduino GPS, and third party projects as SquidBee.

I want to release my hardware!

Can people use a Creative Commons license to release their hardware? Some projects do that, but it's probably not the best way. Creative Commons or GPL licenses only apply to works that can be copyrighted (for example theater plays, pictures, films, musical works, etc.). Creative Common licenses do not apply to the idea presented in the file. The only way to protect an idea is to patent it. After getting a patent you can license it, but patents are time-consuming and expensive, and most individuals can't afford them. So, by using a CC license for releasing an schematic we are really releasing the drawing of the schematic, not the circuit that can be done with it.

There is still another question: copyright rights apply directly: this means that if you compose a song, your authorship is recognized automatically; however, the only way of getting rights over a utilitarian design or an invention is by a patent. So... you all might have released something that theoretically is not yours! Now you may wonder, what would happen if someone else patented my design? Well, in Europe, if you have published it, you have prevented it from being patented--you can't even patent it yourself!

The TAPR organization has contributed to the Open Hardware developers community with an Open Hardware License. As they say in their website, they grant permission for anyone to use the OHL as the license for their hardware project, provided only that it is used in unaltered form. This license is based in GPL but unlike the GPL, the OHL is not primarily a copyright license. While copyright protects documentation from unauthorized copying, modification, and distribution, it has little to do with your right to make, distribute, or use a product based on that documentation. For better or worse, patents play a significant role in those activities. Although it does not prohibit anyone from patenting inventions embodied in an Open Hardware design, and of course cannot prevent a third party from enforcing their patent rights, those who benefit from an OHL design may not bring lawsuits claiming that design infringes their patents or other intellectual property''. This license takes into account aspects like manufacturing and distribution of products made with the documentation released, which are not considered in software licenses. The problem is that this license only affects the documentation related to the hardware, not to the products themselves (which is what happens with software and the GPL). However, the OHL is definitely a good start to build a more complete license.

Conclusion

This article describes the basic concepts behind understanding how to develop Open Hardware. Although a perfect model for releasing it is still not in place, there's an ever increasing community who build Open Hardware.