I was asked by the UK Action Group of the Open Document Format Alliance to write a white paper on the technical differences between ODF and OOXML. After much agonizing, correcting, having others correct my mistakes, suggestions, changes and drafts I still have got something that may be alright to be previewed by all. The actual documents are in ftp://officeboxsystems.com/odfa_ukag both as a “PDF” and an “ODT” (Open Document Format).

The following is a transcribed version of the white paper. Although it has all the Free Software Magazine formatting constraints which means that the information is not as clearly presented, so therefore I recommend you to download the document from the above URL. It is here primary for reference purposes.

Enjoy.

Technical Distinctions of ODF and OOXML

ODF Alliance UK Action Group

A Consultation Document

by

Edward Macnaghten

Introduction

For many years various computer software vendors produced office software. However, it was difficult for a user of one application to reliably manipulate documents that were created by another. The file format specifications were closely guarded secrets, and for interoperability to exist developers would spend large amounts of resources trying to decipher complex “file dumps”.

Obviously a standard was needed, and ODF came to the fore. Soon after, Microsoft suggested that its own OOXML should perform that role instead.

An important point of any standard is the desirability and ease with which it can be implemented. A standard that cannot be implemented by all interested parties within the realm it applies to makes it virtually useless, and only serves to hinder interoperability rather than promote it.

The technical philosophy of the design of a standard is therefore important.

This document reviews the ODF and OOXML formats. It examines some of the nuts and bolts as to how the files are actually formed and the technical merits (or otherwise) of what is created.

This only examines the technical issues; those concerning intellectual property and legal issues are dealt with elsewhere.

ODF Background

History

ODF is a format developed as a vendor neutral standard. However, it did not originate from anywhere inparticular but rather through a process of evolution [1]...

- In 1999 StarDivision began work on an XML interchangeable file format for their StarOffice product.

- In August that year StarDivision was acquired by Sun Microsystems.

- In October 2000, Sun Microsystems released large amounts of the source code to the community driven OpenOffice.org project under an open licence. At the same time an XML community project was created with the goal of defining an XML specification for the interchangeable file format.

- In May 2002 OpenOffice.org version 1.0 and StarOffice version 6 were released using this XML format (SXW).

- Also in 2002 collaboration began with other office suites, notably the KOffice project, to further refine the interoperability of the format.

- In December 2002, OASIS had a conference call announcing the creation of what is now the ODF standard.

- Then, from 2002 to 2004 the format was overhauled based on experiences to date and examination of what is required in an office format.

- In December 2004, a second draft of the XML file format was approved by OASIS for review.

- In February 2005, a third draft was published for public feedback—six years after commencement of the project and five years after public consultation began.

- In May 2005, the ODF format was approved as an OASIS standard [2].

- Soon after that, many office suites adopted the standard as a means to store the documents [3].

- In September 2005, ODF was submitted as ISO standard.

- In May 2006, ODF achieved ISO certification (ISO/IED 26300).

- In February 2007, OpenDocument Version 1.1 had been approved by OASIS [4]. It particularly addresses accessibility issues.

- ODF throughout continued and continues to grow in popularity and support [5].

Philosophy

The phiosophy behind the format was to design a mechanism in a vendor neutral manner from the ground up using existing standards wherever possible. Although this meant that software vendors would need to tweak their individual packages more than if they continued down their original routes, the benefits of interoperability were understood by the participants to be important enough to justify this [6].

This is reflected in the specification in many ways, but specifically:

- XSL:FO—Formatting

- SVG—Scaleable Vector Graphics

- MathML—Mathematical formulas

- XLink—Embedded links

- SMIL—Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language

- Xforms—Forms definitions

OOXML Background

History

OOXML is the format Microsoft developed for its Office 2007 suite. The development of OOXML was not performed with visible public consultation. It is difficult to determine when development of the format started. However, the following is known:

- Microsoft used an XML format as an option in their Office 2003 suite, though it was not the default format. It was not compressed and all data was stored in the single XML file, binary data, such as pictures, being represented as BASE64 strings in special

binDatatags. A strict licence governing use of this format was included. This was released during 2003. - Microsoft started development of Microsoft Office 12, which would be known as “Microsoft Office 2007”. They developed a new XML schema (OOXML), probably using the Office 2003 XML files as a base. Like ODF, the format stores the data in a number of files embedded in a

.zipfile. No visible consultation with the public occurred during its creation. - Under pressure, Microsoft relaxed its licensing terms in January 2005. However, they were not relaxed enough to permit free software to use it [7].

- Shortly after the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ Information Technology Division chose OASIS ODF as a standard for its documents Microsoft announced that it would be submitting its format to ECMA for standardisation [8]. Later that month (November 2005), Microsoft relaxed the licence further as well as placing a mutual Non-Assertive-Clause for the patents they held on it [9].

- In December 2006, ECMA approved OOXML as a standard (ECMA 376) [10]. This was done after no visible public consultation, and approximately two and a half years of development since releasing their previous (Microsoft Office 2003) closed XML format(10). It was almost immediately submitted to ISO to be certified as an international standard later that month.

- In January 2007, a draft of over 6000 pages was released to members for 30 days to analyse and submit “contradictions”.

- Microsoft released Microsoft Office 2007 in January 2007.

- In February 2007, an unprecedented twenty countries submitted comments and contradictions to the standard.

Philosophy

We are of the view that the format appears to be designed by Microsoft for Microsoft products, and to inter-operate with the Microsoft environment. Little thought appears to have been exercised regarding interoperability with non-Microsoft environments or compliance with established vendor-neutral standards [11].

An example of the XML differences between ODF and OOXML word processing files

Introduction

The philosophies behind ODF and OOXML greatly affect the end result. A way to demonstrate this is to review the meat of the file of the same document saved in the different formats. To this end an example document has been assembled, and the appropriate parts of the XML files examined.

Procedure

To do this the following operations were performed:

- A basic 1 page document consisting of a sentence, with some elementary font effects, and a picture, was created. This document has been pasted onto the following page for reference.

- The document was saved both as an ODF (.odt) and an OOXML (.docx) file.

- The resulting zip files were each expanded and explored to find the “meat” of the document. For each this was then extracted.

- The resulting XML for each was then reformatted for readability just by adding indents and line breaks, and by colouring different parts of the text. The same formatting rules and methods were used on each example.

- The formatted XML extract for each is reproduced below.

- An analysis follows the XML extracts.

Although this example shows a relatively small aspect of the two formats, it does highlight the differences between the designs.

The ODF XML Representation of the “meat” of the “Example Document”

<text:h text:style-name="P1" text:outline-level="1">

Example document

</text:h>

<text:p text:style-name="Standard">

This has some

<text:span text:style-name="T1">

bold formatting

</text:span>

, also some

<text:span text:style-name="T2">

with italics

</text:span>

, a

<text:a xlink:type="simple" xlink:href="http://www.odfalliance.com">

<text:span text:style-name="Internet_20_link">

web link

</text:span>

</text:a>

and a picture...

</text:p>

<text:p text:style-name="Standard">

<draw:frame draw:style-name="fr1" draw:name="graphics1" text:anchor-type="as-char"

svg:width="5.9929in" svg:height="5.4362in" draw:z-index="0">

<draw:image xlink:href="Pictures/10000000000002DC00000298CDD44AEF.jpg"

xlink:type="simple" xlink:show="embed" xlink:actuate="onLoad"/>

</draw:frame>

</text:p>

The OOXML XML Representation of the “meat” of the “Example Document”

<w:p>

<w:pPr>

<w:pStyle w:val="Heading1"/>

</w:pPr>

<w:r>

<w:t>

Example document

</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:p>

<w:p>

<w:r>

<w:t>

This has some

</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:r>

<w:rPr>

<w:b/>

</w:rPr>

<w:t>

bold formatting

</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:r>

<w:t>

, also some

</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:r>

<w:rPr>

<w:i/>

</w:rPr>

<w:t>

with italics

</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:r>

<w:t>

, a

</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:hyperlink w:rel="rId4" w:history="1">

<w:r>

<w:rPr>

<w:rStyle w:val="Hyperlink"/>

</w:rPr>

<w:t>

web link

</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:hyperlink>

<w:r>

<w:t>

and a picture...

</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:p>

<w:p>

<w:r>

<w:pict>

<v:shapetype id="_x0000_t75" coordsize="21600,21600" o:spt="75"

o:preferrelative="t" path="m@4@5l@4@11@9@11@9@5xe"

filled="f" stroked="f">

<v:stroke joinstyle="miter"/>

<v:formulas>

<v:f eqn="if lineDrawn pixelLineWidth 0"/>

<v:f eqn="sum @0 1 0"/>

<v:f eqn="sum 0 0 @1"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @2 1 2"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @3 21600 pixelWidth"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @3 21600 pixelHeight"/>

<v:f eqn="sum @0 0 1"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @6 1 2"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @7 21600 pixelWidth"/>

<v:f eqn="sum @8 21600 0"/>

<v:f eqn="prod @7 21600 pixelHeight"/>

<v:f eqn="sum @10 21600 0"/>

</v:formulas>

<v:path o:extrusionok="f" gradientshapeok="t" o:connecttype="rect"/>

<o:lock v:ext="edit" aspectratio="t"/>

</v:shapetype>

<v:shape id="_x0000_i1025" type="#_x0000_t75"

style="width:431.25pt;height:391.5pt">

<v:imagedata w:rel="rId5" o:title="dalek"/>

</v:shape>

</w:pict>

</w:r>

</w:p>

Analysis of the two examples

This section highlights aspects demonstrated in the above example. It is by no means a complete analysis of the differences between the two formats but it does show the philosophical and conceptual thought processes behind each.

Tags and tag naming

To start with, a brief and over-simplified description of a tag. A tag is what XML encloses in the “<” and “>” characters. The name is the first (and sometimes only) part of it. The name is of the format namespace:tagname where the “namespace” is a means of grouping some tags of a particular type together. Should the name begin with a “/” character then that signifies the end of a “block” created with a tag of the same name.

The OOXML has shorter tag names. The benefits to this are firstly a saving of file space, and secondly it facilitates an increase in the speed used of “parsing” the data to convert it to the internal structures the application needs. However a greater number of tags are needed in that format.

The ODF naming is longer and more wordy although it follows the XML convention for naming tags. The benefit to that is it eases interoperability when implementing the standard. File space and parsing performance increases are offset by the fact there are fewer tags required in this format.

The differences in file space and performance are of little significance. Firstly, the ZIP algorithm of the containing files, which each uses, compresses all the tag names to such an extent that they use almost exactly the same amount of file space. Secondly, in modern machines disk access takes the bulk of load time, rendering the processing resource required for parsing tag names insignificant.

The readability and clarity of the tag names influence the adoption of the formats. The cost of implementing the standard such as this is directly related to the resource required to develop the mechanics. If the standard is cryptic, then extra resources need to be deployed both to implement it and support it. There are hundreds of tags in each format and the more unintuitive they are the harder it is for developers to understand, remember and reference them.

Span feature

Again a brief and over-simplified description: “Spanning” is a method of changing the attributes of a section of a block within the block itself. For instance, a bold italic red piece of text might be embedded within a paragraph. A method of storing that in an XML document is to place a tag at the beginning of that section (in the example, specifying the text to be bold and italic), and a terminating tag at the end.

ODF supports the “span” feature, as seen by the text:span tag above.

OOXML does not support this. OOXML needs to end the parent block at the beginning of the change of format and create a new one, then end that block when the format changes back, and create yet another one prior to continuing. This can be seen with the relative proliferation of the w:t, and w:r tags in the example, and makes the document format considerably more complex.

Use of prior standards

The use of existing standards eases the process of creating a compliant product, which is an obvious goal for standards in the first place.

The already-existing “xlink” and “svg” standards can be seen in the ODF XML example above. The design of that format used existing standards wherever possible.

OOXML seems not to apply existing standards in this area. The only standard it appears to follow is the basic XML formatting standard itself. Also some aspects of OOXML can be exceedingly obfuscated, such as the eqn attributes in the v:f tag in the example—“<v:f eqn="prod @3 21600 pixelWidth"/>”.

An example of the XML differences between ODF and OOXML spreadsheet files

Introduction

As with the word processing example above, the spreadsheet file format was examined. Again, the differences between the philosophies of the formats come to the fore on examination.

Procedure

To do this, the following operations were performed:

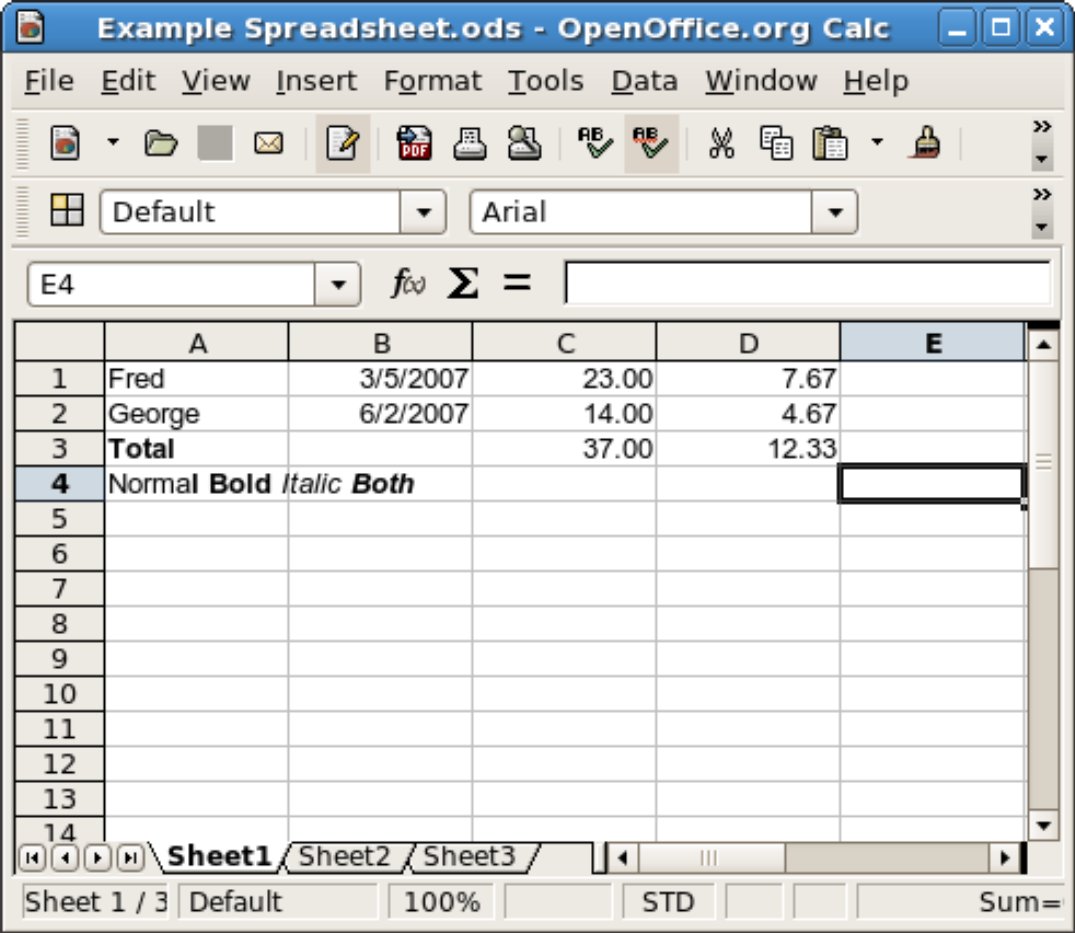

- A basic spreadsheet (represented below) was created, consisting of two rows each consisting of a name, a date, a value and a simple formula. A total row was created with the word “Total” in bold and the sum of the values in the respective columns, and finally a piece of text of a varying format was added.

- The document was saved both as an ODF (

.ods) and an OOXML (.xlsx) file. - The resulting zip files where each expanded and explored to find the “meat” of the document. This was then extracted.

- As with the word processing example, the resulting XML was then reformatted for readability just by adding indents and line breaks, and by colouring different parts of the text. The same formatting rules and methods were used on each example.

- The formatted XML extract for each was reproduced in the pages below.

- An analysis follows the XML extracts.

Example spreadsheet

Contents:

| . | A | B | C | D |

| 1 | Fred | 3/5/2007 | 23.00 | 7.67 |

| 2 | George | 6/2/2007 | 14.00 | 4.67 |

| 3 | Total | . | 37.00 | 12.33 |

| 4 | Normal Bold Italic Both | . | . | . |

Contents of the example spreadsheet

Notes:

- Cells “D1” and “D2” contain the formulas “=C1/3” and “C2/2”

- Cells “C3” and “D3” contain the formulas “=SUM(C1:C2)” and “=SUM(D1:D2)”

- Dates are UK representations (DD/MM/YYYY)

ODF XML Representation of the “meat” of the spreadsheet

<table:table table:name="Sheet1" table:style-name="ta1" table:print="false">

<table:table-column table:style-name="co1" table:default-cell-style-name="Default"/>

<table:table-column table:style-name="co1" table:default-cell-style-name="ce3"/>

<table:table-column table:style-name="co1" table:default-cell-style-name="Defaul"/>

<table:table-column table:style-name="co1" table:default-cell-style-name="ce5"/>

<table:table-row table:style-name="ro1">

<table:table-cell office:value-type="string">

<text:p>

Fred

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce4" office:value-type="date"

office:date-value="2007-03-05">

<text:p>

3/5/2007

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell office:value-type="float" office:value="23">

<text:p>

23.00

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:formula="oooc:=[.C1]/3" office:value-type="float"

office:value="7.66666666666667">

<text:p>

7.67

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

</table:table-row>

<table:table-row table:style-name="ro1">

<table:table-cell office:value-type="string">

<text:p>

George

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce4" office:value-type="date"

office:date-value="2007-06-02">

<text:p>

6/2/2007

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell office:value-type="float" office:value="14">

<text:p>

14.00

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:formula="oooc:=[.C2]/3" office:value-type="float"

office:value="4.66666666666667">

<text:p>

4.67

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

</table:table-row>

<table:table-row table:style-name="ro1">

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce1" office:value-type="string">

<text:p>

Total

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:style-name="Default"/>

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce5" table:formula="oooc:=SUM([.C1:.C2])"

office:value-type="float" office:value="37">

<text:p>

37.00

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce7" table:formula="oooc:=SUM([.D1:.D2])"

office:value-type="float" office:value="12.3333333333333">

<text:p>

12.33

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

</table:table-row>

<table:table-row table:style-name="ro2">

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce2" office:value-type="string">

<text:p>

<text:span text:style-name="T1">

Normal

</text:span>

<text:span text:style-name="T2">

Bold

</text:span>

<text:span text:style-name="T3">

Italic

</text:span>

<text:span text:style-name="T4">

Both

</text:span>

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

<table:table-cell table:number-columns-repeated="2"/>

</table:table-row>

</table:table>

OOXML XML representation of the “meat” of the Spreadsheet

Excerpt from the “sheet1.xml” file

<sheetData>

<row r="1" spans="1:4">

<c r="A1" t="s">

<v>

0

</v>

</c>

<c r="B1" s="1">

<v>

39146

</v>

</c>

<c r="C1">

<v>

23

</v>

</c>

<c r="D1" s="2">

<f>

C1/3

</f>

<v>

7.666666666666667

</v>

</c>

</row>

<row r="2" spans="1:4">

<c r="A2" t="s">

<v>

1

</v>

</c>

<c r="B2" s="1">

<v>

39235

</v>

</c>

<c r="C2">

<v>

14

</v>

</c>

<c r="D2" s="2">

<f>

C2/3

</f>

<v>

4.666666666666667

</v>

</c>

</row>

<row r="5" spans="1:4">

<c r="A5" s="3" t="s">

<v>

2

</v>

</c>

<c r="C5">

<f>

SUM(C1:C4)

</f>

<v>

53

</v>

</c>

<c r="D5" s="2">

<f>

SUM(D1:D4)

</f>

<v>

12.333333333333334

</v>

</c>

</row>

</sheetData>

OOXML Spreadsheet—“sharedStrings.xml” file

<sst count="4" uniqueCount="4">

<si>

<t>

Fred

</t>

</si>

<si>

<t>

George

</t>

</si>

<si>

<t>

Total

</t>

</si>

<si>

<r>

<t>

Normal

</t>

</r>

<r>

<rPr>

<b/>

<sz val="10"/>

<rFont val="Arial"/>

<family val="2"/>

</rPr>

<t>

Bold

</t>

</r>

<r>

<rPr>

<sz val="10"/>

<i/>

<rFont val="Arial"/>

<family val="2"/>

</rPr>

<t>

Italic

</t>

<rPr>

<sz val="10"/>

<b/>

<i/>

<rFont val="Arial"/>

<family val="2"/>

</rPr>

<t>

Both

</t>

</r>

</si>

</sst>

Analysis of the two examples

The XML for spreadsheets is more “fiddly” than the one for word processing. The reason for this is that it needs to organise the data into a table, rows, columns and cells. As before, the above is not a complete representation of the entire XML files but it does highlight the differences in philosophy.

Tags and tag naming

The same applies to spreadsheets as it does to the word processing example. Short tag names in OOXML simply means the specification is somewhat cryptic. For example, what DOES “

Storage of text

An almost immediate “feature” of OOXML is that there is no “string” or “text” data in the main content area of the sheet’s XML. Instead there are references to a special “sharedStrings.xml” file. Where the type of the cell is text, OOXML sets the t attribute in the c tag to be value s, and the body contains a number representing the nth item (starting from zero) of a list of strings stored in the sharedStrings.xml file. The stated reason behind this is to reduce the size of the file by consolidating duplicate text entries of the spreadsheet to save space.

Cell value (A1)

Fred

ODF representation

<table:table-cell office:value-type="string">

<text:p>

Fred

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

OOXML representation

<c r="A1" t="s">

<v>

0

</v>

</c>

Another peculiar “feature” of the OOXML’s treatment of text is the inconsistent formatting. The cell’s formatting style is defined in the cell’s tag (the c tag) using the s attribute, which contains a number that cross references to the nth item, starting from zero, of a list of fonts defined in the “styles.xml” file (n being the number defined in the s attribute). The inconsistency appears when examining a cell with varying text formats, where some of the formatting is defined in the si tag in the sharedStrings.xml file, but explicitly instead of using “font item numbers” references as the main file.EDITOR: This last sentence from "but explicitly..." doesn't make sense to me. Please review it.

The ODF format renders above complexity unnecessary. ODF only uses a style-name attribute that cross references a style table. This is consistent throughout the ODF specification:

“<...style‑name="ce5"...>”.

Date representations

Cell value (B1)

3/5/2007

ODF representation

<table:table-cell table:style-name="ce4" office:value-type="date"

office:date-value="2007-03-05">

<text:p>

3/5/2007

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

OOXML representation

<c r="B1" s="1">

<v>

39146

</v>

</c>

An important aspect is the treatment of dates. OOXML stores the dates 5th March 2007 and the 2nd June 2007 as the numbers 39146 and 39235 respectively. This is the number of days since 31st December 1899. However, there is a “design bug” in the specification that states that the year 1900 needs to be treated as a leap year, which it is not. If a particular setting is altered in the OOXML format, the above numeric representation changes to the number of days since 1st January 1904, avoiding this problem.

ODF represents the dates 5th March 2007 and 2nd June 2007 as “2007-03-05” and “2007-06-02” as in accordance with the existing ISO standard.

Redundancy in numeric and date cells

Cell value (C1)

23.00

ODF representation

<table:table-cell office:value-type="float" office:value="23">

<text:p>

23.00

</text:p>

</table:table-cell>

OOXML representation

<c r="C1">

<v>

23

</v>

</c>

(also see date example above)

OOXML simply stores the numeric value in each table cell unless there is a formula, in which case it stores that and the result of the formula. ODF always stores the numeric value as an attribute and the formatted representation in the body, as well as the formula as an attribute if it exists. This means ODF stores redundant data. One rationale behind this is that although it is a little more complicated to create, it is a lot easier to read. A program inquiring on the spreadsheet can extract either the value or the formatted text easily, whereas in OOXML, extracting the formatted text is highly complicated. The other rationale deals with consistency within the specification, which is covered in the next section. A rationale for OOXML omitting this redundancy is that it creates larger files.

Consistency with the rest of the specification

ODF’s table specification for spreadsheets is identical to the table definition used in the word processing documents. The tags and the attributes are the same. In fact, the “Table” definition only occurs once in the specification and the spreadsheet and word processing table sections simply refer to it. This simplifies the task of implementing the specification as well as making it shorter. In the OOXML specification, the same is not the case. The tag and attribute names and structures differ. There are some formatting similarities for the cells with a variable format. However, they are not stored as part of the table data but in the “sharedStrings.xml” file, making simple portability very difficult in practice.

Summary of differences

The differences between the formats appear to reflect their respective philosophies. The emphasis of OOXML appears to be on representing the data the Microsoft Office applications use and reducing file sizes to save space and enhance performance. The emphasis of ODF appears to be one of interoperability, ease of implementation and access to the data.

The file space savings of OOXML are all but obliterated through the ZIP algorithm of the containing file that the formats use. This reduces the redundancy without complicating the formats themselves. Also, performance enhancements of shorter tag names are insignificant to the resource required by the computer to retrieve the data from the disk, memory card or network.

Although OOXML is better designed for use with Microsoft Office products, the use of meaningful tag names, explicit representations of data and consistency throughout the specification will make ODF more interoperable and easier when implementing the format in different scenarios.

Unique application configuration settings

For an open format to be adopted it needs to be the default means of saving data for the applications adopting it. This presents a problem.

The problem

An office manipulation program, such as a word processor or spreadsheet, will have quirks that are unique to it. For instance, Microsoft’s Word 2003 has compatibility options such as “Auto Space like Word 95” and “Convert backslash characters into Yen signs”. By the same token, OpenOffice.org 2.0 Writer has options to “Use OpenOffice.org 1.1 tabstop formatting” and “Consider wrapping style when positioning objects”. These options are unique to their respective applications, and have no place in the interoperability of the documents themselves; other applications run a risk of not knowing how to interpret them. They can, however, mean competitive advantages for one application over another.

This information needs to be included somehow. The reason is that, should an application save its data on a local disk, then, after reloading the data, it is important that these unique application configuration settings are maintained.

The above does mean that it’s likely that the precise rendering of a document is slightly different when transferring it from one application to another, regardless of format used. However, this is not relevant when considering the fact that the same office application often renders differently from one version to the next, or even that the same version of the same office application running on the same operating system will render differently depending on the machine on which it is run. Peripheral items like fonts installed and different printers attached can affect rendering.

Should precise rendering of a document be required then there are standards for that, notably PDF. In these circumstances no editable office document format should be used.

The problem the specification designers need to solve is how to maintain these application-specific settings in an open document format.

The ODF Solution

ODF’s solution is the adoption of a configuration tag. An example follows:

Sample of ODF configuration settings for OpenOffice.org

<config:config-item-set config:name="ooo:configuration-settings">

<config:config-item config:name="PrintPaperFromSetup" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="AddFrameOffsets" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="PrintLeftPages" config:type="boolean">

true

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="PrintReversed" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="PrintTables" config:type="boolean">

true

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="LinkUpdateMode" config:type="short">

1

</config:config-item>

</config:config-item-set>

The particular configuration parameter is stored in the config:name attribute, the type of the parameter’s value in the config:type attribute and the configuration setting in the body of the tag itself.

As shown above, all the parameters are also enclosed within a config-item-set tag which is specific for the application, which means identical config:name values for different applications will not clash.

These unique settings mean nothing to other applications, so they are ignored when they load the document, and are, as far as functionality is concerned, irrelevant.

Here is a possible scenario.

In the future, it would be practicable for ODF aware applications to create a “generic” or “alien” configuration panel in their settings option that simply stores and lists unknown configuration settings it finds. The tag itself states what type of setting it is in a human-readable form, so theoretically modification of these would be possible too. When the document is saved for transfer then these settings could be included in the file. This means when one person creates a document, setting some of their application’s configuration in their own way, then transfers it to a second person who edits the document using a different application, saves it and passes it back, the first person would be able to edit the file and the unique application’s configuration settings would have been kept.

The OOXML solution

OOXML chose this route. Rather than create an application-definable configuration tag there is a unique tag for each setting. An example follows:

Sample of OOXML configuration settings for Microsoft Office

<w:compat>

<w:doNotSnapToGridInCell/>

<w:doNotWrapTextWithPunct/>

<w:doNotUseEastAsianBreakRules/>

<w:growAutofit/>

<w:footnoteLayoutLikeWW8/>

</w:compat>

There are well over a hundred of these tags defined in the specification.

Although OOXML’s version on the face of it seems simpler, it adds additional complications for adoption of the standard. Currently, the only application’s unique settings that are catered for are the applications that the standard’s authors have decided to include, which would appear to currently consist of the Microsoft Office suites. For other applications to be added, further tag names would need to be defined in the specification, potentially creating thousands of them, each having nothing to do with interoperability.

A new application vendor could get around this by unilaterally devising their own home-grown tag names and using those. However these would break the specification. Also as the specification does not define a method of placing these tags within a container tag creating your own tags could lead to a possibility of a clash with other applications.

Furthermore, there seems no obvious way for an application using OOXML to display “alien” configuration settings in its own panel. Although the application could theoretically store the tag names and associated values, there is no guaranteed way of knowing what the type of the attribute is, making it much harder to present and nearly impossible to make changeable with any validation at all. This is made worse by the fact that boolean values are decided by the existence or otherwise of a tag rather than a value in its body, meaning that the only way to find if it is unset is to look for it and see if it is not there.

Interoperability between applications regarding configuration settings

If Microsoft were to adopt ODF for Office, it could cater for all its unique settings by the way that specification is defined at the moment. The above example could be represented as:

How some Microsoft Office configuration settings could be represented in ODF

<config:config-item-set config:name="mso:compatability-settings">

<config:config-item config:name="SnapToGridInCell" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="WrapTextWithPunctuation" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="UseEastAsianBreakRules" config:type="boolean">

false

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="AllowTableExpandBeyondMargin" config:type="boolean">

true

</config:config-item>

<config:config-item config:name="EmulateWW8FootnotePlacement" config:type="boolean">

true

</config:config-item>

</config:config-item-set>

Although the above would still be alien to non Microsoft Office applications they could easily be made to store them and to reproduce them when the file is saved.

However, should OpenOffice.org adopt OOXML, there is no current way that it can add its configuration settings using the standard:

How some OpenOffice.org configuration settings could be represented in OOXML

***** UNABLE TO DO IT *****

Contradictions in OOXML

Upon examination of the OOXML specification, a number of contradictions between it and existing standards emerged. Some of these are listed below. These are expressed as the form of the contradiction, one or more rationales used to defend OOXML, and a response to each rationale.

OOXML duplicates and overlaps ODF

It is clearly pointless to have OOXML when ODF already exists as a standard for office document interoperability. The cost penalties to industry, governments and other institutions to implement two standards instead of one are self evident and should be uneccessary.

Rationale: standards can overlap

Standards already exist that overlap with each other, such as HTML, PDF/A and ODF for exchanging office documents, CGM and SVG for vector graphics, JPEG and PNG for image formats, RELAX NG and DTD for XML schema definitions and TIFF/IT and PDF/X for publishable graphics.

Response:

Standards should not overlap. In the examples given, HTML, PDF/A and ODF are used for very different types of document interchange, CGM and SVG are used for different purposes, JPEG and PNG handle different types of images and PDF/X was created because of shortcomings of TIFF in certain areas.

Where a standard exists for a purpose then it should be used for that. It is pointless to create a competing standard for its own sake. It seems illogical to create a competing standard when one already exists and is meeting industrial strength requirements. To intentionally create a standard that is known simply to duplicate the functionality of another just results in extra costs with no benefits to those who need to adopt it.

Rationale: OOXML has a distinct purpose of storing existing Microsoft Office documents

OOXML is different to ODF in that OOXML was designed with compatibility with existing Microsoft closed formats and ODF was designed for document interoperability.

There are many existing Microsoft Office documents in existence; a standard should exist that reproduces the precise formatting of these documents as originally written. Those that require this include national library archives and mission critical scenarios. Also, persistence of this precise formatting is required when moving data to and from other platforms such as mobile and fixed computers.

Response:

The purpose of an editable document standard is interoperability, otherwise there is no point to it. Also, after examination of the specifications, no technical reason can be found why Microsoft Office cannot store its files using ODF as reliably as with any other format.

Rationale: OOXML and ODF can co-exist

The fundamental differences between ODF and OOXML means they cannot be merged. OOXML was designed to be compatible with Microsoft Office documents, and ODF was designed for document interchange; this as well as some “nitty gritty” differences makes merging them impossible. However, translators can be written, are being written and have been written to convert from one format to the other; therefore co-existence is possible. This means there is no contradiction between the two.

Response:

The two points above cancel each other out. Although OOXML and ODF have too many namespace and structural differences to be merged, ODF can store documents created for OOXML, but not vice-versa. OOXML therefore should not be a standard.

Objection: OOXML has inconsistencies with existing ISO standards

OOXML has inconsistencies with the following standards:

| Standard | OOXML Ref | Description |

| Page Size Names (ISO 216) | 3.3.1.61, 3.3.1.62 | ISO 216 defines names for pager sizes, OOXML uses its own numeric codes for these sizes rather than the existing standard. |

| Language codes ISO 639 | 2.18.52 | OOXML defines its own language codes that are inconsistent with the standard |

| Colour Names ISO/IEC 15445 (HTML) | 2.18.46 | Not only does OOXML sometimes redefine some colour names, but it also redefines some colours corresponding to names belonging to the standard. The colours “dark blue”, “dark cyan”, “dark gray”, “dark green”, “dark red” and “light gray” are different in OOXML to the existing standard. |

| Dates and times ISO 8601 | 4.17.4.1 | OOXML represents the dates as integers from 31st December 1899 with the caveat that 1900 needs to be incorrectly considered a leap year, or 1st January 1004 depending on a configuration setting. This is enormously inconsistent with the standard which represents the date more descriptively. |

| Readable XML ISO 8879 | Almost all | Tag names such as

scrgbClr

,

algn

,

dir

,

dist

,

rPr

rotWithShape

and

w

are neither consistent nor human-readable. There are many other examples. |

OOXML inconsistencies with existing standards

Rationale: page sizes

The ISO 216 page sizes are represented in OOXML, as well as others. OOXML simply uses a number to represent each page size and the specification documents the correspondence. Also, ODF does not use ISO 216 but page size measurements.

Response:

If page names and codes are to be used then it seems sensible that it should be standard ones. For instance, if a size of Letter, A4 or C4 is to be defined then it makes sense for the attribute value to be “Letter”, “A4” or “C4”, not “1”, “9” and “30” (as it is in OOXML).

There is a good argument stating that ODF should use ISO 216 names. However it does not contradict that by making up its own names, but stores the page’s dimensions instead.

Rationale: language codes

OOXML gives the implementer a choice. Either the ISO 639/ISO 3166 combination can be used or a special two byte hexadecimal value as specified in the document.

Response:

If a standard is there, and it does the job, then it should be used. Putting these “optional alternatives” in is pointless and only detracts from adoption. The ISO 639 and 3166 codes should be used alone, then if Microsoft were to drop the hexadecimal codes that would ease adoption.

Rationale: colour names

OOXML uses its own abbreviations for colour modifications: “dk” for “dark”, “lt” for “light” and “med” for “medium” for colour highlighting. It also uses its own description of colors such as “darkRed” (OOXML) for “maroon” (ISO 15445) and “darkCyan” (OOXML) for “teal” (ISO15445); these are more meaningful.

Response:

The purpose of standards is that if everyone uses them it will make the world a more meaningful place. Unilaterally defining alternative and/or redefining the actual colours in a standard that is supposedly open is a contradiction, and as they vary from the standard they are less meaningful.

Rationale: dates and times

There are legacy applications, such as Microsoft Excel and Lotus 123 that treat the year 1900 as a leap year. The two methods of converting numbers to dates are to help cater for that. The first (the number of days since 31st December 1899) is to cater for the legacy applications: the second (the number of days since 1904) gives a more accurate representation for newer applications. Although the range of dates supported for OOXML (12-December-1899 or 1-January-1904 to 21-December 1999) is not as big as the range for ISO 8601, it should suffice.

Response:

The interchangeable document format should not be handicapped by the limitations of any application. Should an application need to store dates as a number it can convert them when loading the interchangeable format, and convert them back when saving it. ISO 8601 specifies an unambiguous method for interchanging dates, there is no reason why it cannot be used.

Rationale: terse tag names

Other SGML standards have terse tag names. For instance, the HTML standard has tag names such as <P>, <HR>, <TR>, <TD> and so on. OOXML is a specification for a technical markup language and it is not unreasonable to expect direct manipulation and implementation to be done with a reference manual.

Response:

OOXML is supposed to be a standard for document interchange that uses XML. One of the advantages of XML is that descriptive tag and attribute names can be used: this makes understanding and implementation of the standard easier. Using short and/or inconsistent abbreviations is not considered good practice in an open standard.

The original version of HTML had about thirty tags, making it relatively easy to remember them all despite their cryptic nature, whereas OOXML has several hundred, making the sane naming of tags all the more important.

OOXML inconsistencies: references to external or redundant non-standard resources

| Resource | OOXML Ref | Description |

| Vector graphics | 14, 8.6.2 | OOXML defines its own vector graphics XML—DrawingML. But the recognised standard for this, also recommended by W3C, is SVG. OOXML also includes Microsoft’s VML specification in contradiction to both SVG and DrawingML. VML was turned down as a W3C standard in 1999 in favour of SVG. |

| Objects | 6.2.3.17 6.4.3.1 | OOXML references Windows Metafiles and Enhanced Metafiles, both closed proprietary Microsoft formats. |

| Configuration | 2.15.3 | OOXML contains specific application configuration settings, most notably: autoSpaceLikeWord95, footnoteLayoutLikeWW8, lineWrapLikeWord6, mwSmallCaps, shapeLayoutLikeWW8, suppressTopSpacingWP, truncateFontHeightsLikeWP6, uiCompat97To2003, useWord2002TableStyleRules, useWord97LineBreakRules, wpJustification and wpSpaceWidth. |

| Percentages | 2.15.1.95, 2.18.97, 5.1.12.41 | The OOXML standard is inconsistent within itself, as well as with recognised methods, of the representations of percentage values, which can be expressed as a decimal integer (Magnification Settings—2.15.1.95), as a code made up of an integer being the real percentage multiplied by 500 (Table Width Units—2.18.97) and a real percentage multiplied by 1000 (Generic Percentage Unit—5.1.12.41). |

OOXML references to external or redundant non-standard resources

Rationale: vector graphics

Although SVG caters for most of VML and DrawingML it does not cater for all. OOXML was designed to meet the needs of interpreting legacy documents. These would contain VML graphics, and the later ones would contain graphics that can easily be converted to DrawingML. In order to reproduce them it is necessary for applications to interpret these graphics.

Response:

SVG is extensible. It would have been easy to extend SVG using OOXML namespaces to cater for the functionality of VML and DrawingML, maybe for inclusion in a later version of SVG. ODF did that.

These legacy documents mentioned would not currently exist in OOXML so would need a translator to convert them from the closed formats. This could just as easily be used to convert the VML and DrawingML’s predecessor formats to the SVG derivative.

Rationale: Objects

The first reference to this—“Embedded Object Alternate Image Request Types” (6.2.3.17)—the OOXML format mentions these formats in enumeration lists, and any formats can be included. The specification does not limit embedded graphic types to Microsoft formats. ODF performs a similar distinction by singling out Java applets. The second—“Clipboard Format types” (6.4.3.1)—simply specifies suggested action taken by the application in certain circumstances and again does not limit the document’s embedded graphic format types.

Response:

The enumeration list mentioned in the first instance (6.2.3.17) includes: Bitmaps, Enhanced Meta Files (EMF) and any other picture format. If all formats can be handled there is no need to include the Microsoft closed formats specifically, and they should not be in an “open” standard.

Although Java is not an ISO standard it is well documented and its main implementation is about to be released as free software. There are large differences between this and the closed Microsoft Meta-files.

The second instance should not be specified in an open document standard at all. The precise behaviour of a particular application for particular (closed) formats is unique to it and not really transferable. Document standards are for interoperability of the document itself, not a determination of how any particular application behaves. Should this be needed for Microsoft Office then it should be stored in a more generic, application defined, “config”-type field that does not infringe on other applications.

Rationale: application specific configuration tags

These are relatively few when compared to the large number of fully documented tags in OOXML. Also, it is not necessary for the implementer of the standard to cater for these. They are settings specific to those applications, so those applications can behave in a consistent manner between saving and loading.

It is worth noting that ODF and OpenOffice.org have a similar, though undocumented, case in ISO 26300, namely the use of the config:config-item tag and the config:name attribute value for what is set. Notable examples are when OpenOffice.org sets the attribute value to AddParaTableSpacingAtStart or UseFormerLineSpacing, or when KOffice sets this to underlinelink or displayfieldcode.

Response:

No open office document standard can be perfect and cater for every application’s quirk and scenario, but these applications need to store their own unique meta information and sometimes unspecified peculiarities for consistency between sessions.

To this end, OOXML seems to cover a more limited range of applications—namely the ones in Microsoft Office and some WordPerfect formatting which Microsoft supports—place the features in the main name-space specification and then ignore all other applications.

ODF, on the other hand, provides an extensible mechanism for any application to add its unique quirks without breaking the standard. It does this by placing the “quirk” in a “config” attribute value defined by the application, not a tag name, and placing the setting in the body of that tag. This is covered in detail in the section “Unique application configuration settings” above.

Rationale: percentages

Where the percentages are actual values they have been converted to integers to allow for efficient parsing. Fractions of a percentage are catered for by multiplying the actual percent by a number.

Response:

The overhead for converting a percentage value such as “27.32” into an equivalent internal integer value of, for example “27320” is trivial. So much so that compared to the processing resource used and time spent by the computer retrieving the document data from a disk, memory card or network the overhead of that calculation would be unnoticeable.

The fact that sometimes OOXML specifies the percentage should be multiplied by 500 in some circumstances, and 1000 in others simply enhances the contradiction.

An open editable document specification should represent percentage values as percentages, that is a number between zero and one hundred representing from none to all.

Conclusion

Standards exist for interoperability, and office document format standards should not be different. The goal is that someone in country A working for company B using product C can interchange documents with someone in country D working for company E using product D without any thought as to what precisely A, B, C, D, E or any other letter actually is. It simply works. There is no need to worry if any single vendor would continue in the office suite business or not, as any other vendor could be used.

ODF was created using existing standards with this interoperability in mind, using long public consultation and design periods to achieve this. The benefits of this are evident when examining the resulting formats themselves.

It has been implemented by a large number of office products and the list is growing.

OOXML was designed by a single vendor, Microsoft, with no extensive public consultation or design input. It was largely designed to co-exist with their legacy formats using their own products. The design of the specification is such that might happen if their own legacy closed binary formats were simply XML-ised—that is binary encodings simply converted to arbitrary XML tags.

Upon examining the formats it is difficult to ascertain any technical reason why Microsoft Office documents cannot be saved and interchanged using ODF with one hundred percent reliability. ODF has the features that will deal with all Microsoft Office’s quirks, even ones like “footnoteLayoutLikeWW8”. However, OOXML in its current state cannot handle any applications except Microsoft Office.

It is my opinion that Microsoft peculiarities in OOXML, together with the fact the specification is over 6000 pages long, would greatly hinder the ability of other parties to develop products that would completely, or near completely, read and manipulate documents in that format and to the extent that it would render it practically difficult to work with as a universal standard.

Notes:

Note 1: Form the OASIS document Open by Design—http://www.oasis-open.org/committees/download.php/21450/oasis_odf_advantages_10dec2006.pdf.

Note 2: OpenDocument Format version 1.0 can be found at http://www.oasis-open.org/committees/download.php/12572/OpenDocument-v1.0-os.pdf.

Note 3: An up to date list of ODF applications is at http://opendocumentfellowship.org/applications.

Note 4: OpenDocument Format version 1.1 can be found at http://docs.oasis-open.org/office/v1.1/OS/OpenDocument-v1.1.pdf.

Note 5: A description of OpenDocument Format adoption can be seen at Wikipedia's OpenDocument adoption page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenDocument_adoption.

Note 6: Form the OASIS document Open by Design referenced in note [1]:

The OpenDocument Format was designed to be vendor neutral and implementation agnostic. It was designed to be used by as many applications as possible. In order to simplify transformations and to maximize interoperability, the format reuses established standards such as XHTML, SVG, XSL, SMIL, XLink, XForms, MathML, and Dublin Core.

Note 7: Dissecting Microsoft’s “Patent License” at http://www.groklaw.net/article.php?story=20050330133833843#A4.

Note 8: Precise history is documented at http://www.groklaw.net/staticpages/index.php?page=20051216153153504.

Note 9: Microsoft Non Assertive Contract can be viewed at http://www.microsoft.com/interop/osp/default.mspx.

Note 10: From ECMA’s web site—http://www.ecma-international.org/:

Ecma is the inventor and main practitioner of the concept of “fast tracking” of specifications drafted in international standards format through the process in Global Standards Bodies like the ISO.

Note 11: In the ECMA’s “Office Open XML Overview” found at http://www.ecma-international.org/news/TC45_current_work/OpenXML%20White%20Paper.pdf it states:

OpenXML was designed from the start to be capable of faithfully representing the pre-existing corpus of word-processing documents, presentations, and spreadsheets that are encoded in binary formats defined by Microsoft Corporation.

References:

GrokDoc OOXML Objections: http://www.grokdoc.net/index.php/EOOXML_objections.

Open Malaysia: http://www.openmalaysiablog.com/.