This year’s Python Convention [1], being held this weekend in Dallas Texas, started off with an inspiring presentation by an engineer from the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project 2 , showing off the hardware features of the new “OLPC XO 1” prototype, as well as some “dangerous ideas” about its software design: a large part of the user space code for the laptops will be implemented in Python, mainly because of the ease of manipulating the source code. The OLPC laptop software will be 100% free software, not just in principle, but in spirit as well—the assumption of open source design is literally built into the hardware.

It’s all free software

It’s not at all surprising that the OLPC laptop’s operating system will be based on Linux, of course—people do that with just about any new embedded device these days. But the motivation for OLPC goes much deeper than that. Citing the importance of open source as an educational value, Krstić suggested that a programming language “where the program was the source” was what was called for, and the selected language is Python. It makes it particularly easy to make source both available and easy to modify and use, since it is an interpreted environment. This greatly reduces the burden of including the source on each unit (where storage space is limited).

In his “Dangerous Ideas” presentation, Krstić lamented the “great lie of open source”: namely that it is enough simply to make the source code available for a piece of software (leaving the problem of setting up a development and build environment and learning how to use it as “an exercise for the user”). He also noted that the average user of this laptop is expected to be a 6-year-old gradeschooler. Thus, the laptop goes several steps further:

- By using Python, which eliminates the problem of compiling and linking

- By writing almost all userspace code for the laptop (including the GUI and the filesystem) in Python

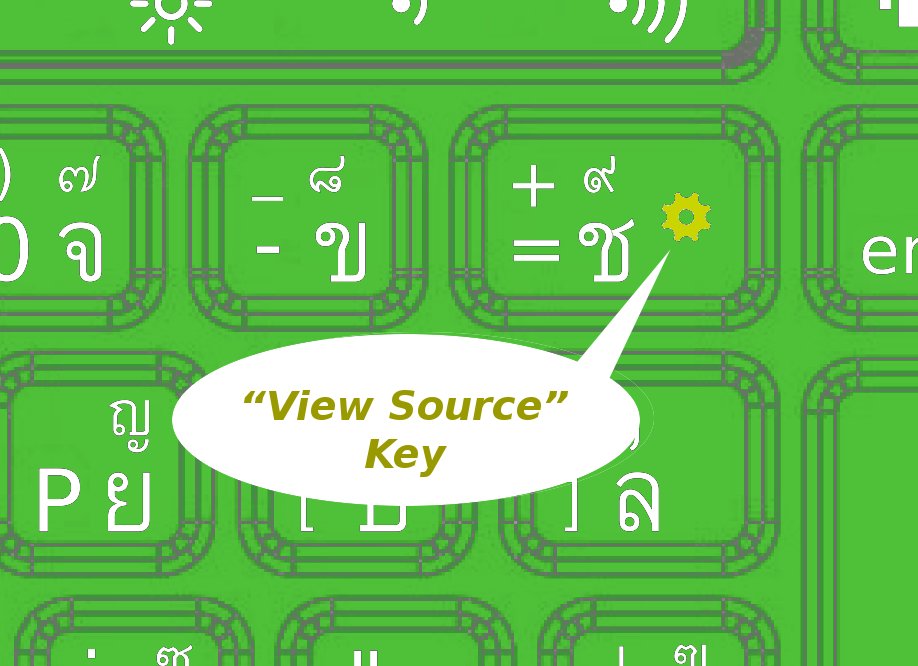

- By actually building a “View Source” special function key on the keyboard, as support for the “Develop” activity (one of several activity-based interface elements on the laptop)

Having made the decision to use Python, the OLPC group has decided to run all the way with the idea. Much of the underlying userspace code for the platform will be developed as a Python project, including the graphical user interface, called “Sugar”. Perhaps the most remarkable innovation will be the “filesystem” which will be implemented as a version-controled “object store” called “Yellow” (this is reminiscent of Zope’s “object file system” or of a Subversion “repository”). This provides a number of spinoff features, including built in “undo” journeling/versioning, which is unheard of in ordinary Linux filesystems, as well as unique capabilities such as advanced local searching abilities. The underlying true filesystem, “JFFS2” also provides built-in wear-levelling capability, since it will be physically based on Flash memory modules.

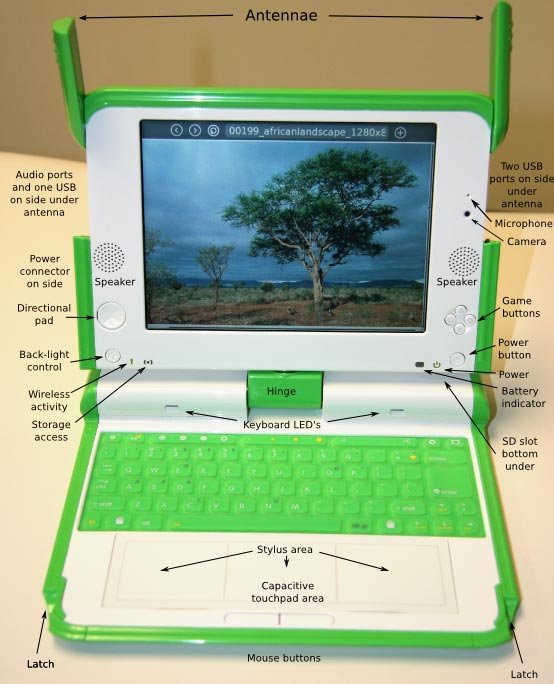

The hardware innovations in the laptop are remarkable in their own right, though this has been more widely reported (so I won’t take up too much time repeating). Among the more impressive are:

- The dual-mode 7.5″ LCD which will function as either a backlit color display at 692×520 or as a direct sunlight visible reflective monochromatic display at 1200×900 pixels

- The LiFePO4 batteries which are lower toxicity, cooler operating, and much lighter than prior laptop LiMH batteries

- The completely autoconfiguring 802.11s ESS mesh networking system, along with the “rabbit ear” antennas that have been reported to work over a range of up to 2km

- The extremely low power design that runs off of about 4-5 Watts (peak) of electricity, along with a power supply that can be hooked up to just about anything that produces electricity (including some hand-powered devices—the integral hand crank from earlier models was eliminated because it wasn’t considered durable enough, a pull cord device is being considered to fill the same role)

View Source!

While Bulletin-boards provide a layer of abstraction on top of any given activity, the View Source button allows one to look behind the activity, peeling away layers of abstraction in order to reveal the underlying codebase which makes it tick. This feature will integrate cleanly with the Develop activity, encouraging children to view, modify, and redistribute variations on the activities they use. Through collaboration and sharing, a garden of home grown activities will begin to develop on the laptops, created by the children themselves..

—— OLPC Wiki

Another feature of dynamic languages that Krstić favored was the simplicity of creating plugin architectures and the resulting reduction of bloat. He described an amazing example of a CD-ROM burning package, which grew from 28 MB in 2004 to 398 MB in 2007. Addressing some of the reasons for this kind of excess, he notes that users often want just one new feature, but are forced into a total upgrade in order to get it, resulting in them acquiring much more code that they don’t really want. By focusing on a small core design with plugins to provide extra deatures, though, he believes the overgrowth of packages can be greatly reduced. These are, of course, vital issues for the OLPC machine, since it has limited storage space.

The user interface guidelines for the XO may represent the greatest examination of the user experience since the first Macintosh computers were made by Apple, and the Sugar project is sure to produce wide-ranging spinoff improvements in GNU/Linux interface design in general, as well as specific improvements aimed at younger users.

These are ambitious improvements, and the schedule for producing the first OLPC laptops (10 Million expected to be delivered later this year) is fairly tight, so there is a need for free software programmers familiar with Python to help participate in developing and improving the code. The public releases of Yellow is not up to date yet, but Krstić reports that it will be available sometime during the next couple of weeks. The “Sugar” UI is basically ready now, and can be downloaded from the project’s development site.

Why?

Although I personally find the OLPC laptop idea immediately compelling, Krstić did spend some time explaining the motivation behind the project, citing his own experiences from growing up in Croatia, and seeing the huge difference between good and poor education among his former schoolmates. He also pointed out some interesting figures about the sheer scale of the problem, noting, for example that the “top 25% by IQ in China is larger than the total population of North America”.

He notes that traditional education is dependent on having great teachers, and that for much of the world, there just aren’t any. Re-engineering the world’s school systems would be a huge project, which he suggests might take 50-100 years at best to implement. Instead, the OLPC project will focus on self-directed learning, by providing a tool to enhance children’s own natural impulse to learn via exploration. Thus, the OLPC laptop is designed from the ground up to be the most transparent learning device that it can be.

Return on Investment

Krstić himself mentioned only a little bit about the impact of 100 million children being exposed to laptop computers and the internet, let alone a view source key inviting them to learn one of the most powerful free software oriented programming languages in one of the most powerful free software operating systems. He suggested that comp.lang.python “might get a bit crowded”. (In fact, only about 10 million will be deployed this year (2007), with an expected 50 million in 2008 and more to come after that).

However, I want to challenge your imagination a bit further, with a few numbers to contemplate. Recently, I’ve been making a study of the size, value, and effort involved in creating Debian GNU/Linux. I plan to publish a bit of that research here in my blog later this month, but to be brief, Debian Sarge consists of about 215 Million Physical Source Lines of Code (SLOC), which, if evaluated for replacement cost as a proprietary software product, using the COCOMO cost model is worth about US$10 Billion (this is a kind of lower limit, since it represents the cost of development)[3]. It’s difficult to estimate the true number of participants in creating Debian, but my back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests that the number of people responsible for creating that code is about 20,000 (including the 1500 official Debian maintainers, 8000 developers for each of the 8000+ source code packages, and some guestimates of the number of developers working on big projects like Linux, Mozilla, and OpenOffice.org).

Now let’s suppose that out of every 1000 children who get an OLPC laptop in the next few years, just 1 really gets into the “View Source” key and begins, after a few years, to participate in the development of free software. That would be an influx of 100,000 new developers. Approximately five times the entire development force that made Debian. Presumeably, as they mature, they will become as productive (the “first world” having no monopoly on intelligence or skill). They would reasonably be expected to produce about US$ 50 billion worth of free software. That’s nothing to sneeze at, even here in the United States, but remember that this is software of, by, and for the people in countries which are currently much poorer. This is, for comparison, about 25% of the entire Gross Domestic Product of Nigeria![4]

And that’s based on a participation rate of just 0.1%. Imagine what would happen if the participation rate were to tick up to just 1%! Imagine what would would happen to online content if just 1% contributed, say, one photo a month to Flickr, using the VGA-resolution camera (also standard on the OLPC XO 1)—that’s 12 million photos a year. What about contributions to Wikipedia, especially in improving their native language editions? With that kind of power, it might not be unreasonable to assume that, a few years down the road, the next generation global teaching tool will be designed and built by those kids. That wouldn’t be a bad return on investment.

Yes, these are “dangerous ideas” indeed.

[3] This is from a study by Libre Software Engineering

[4] This is a value-to-value comparison, based on the value of all products created in Nigeria at US prices. The cash value of Nigeria's GDP is even lower. Data from CIA World Fact Book, 2006.

License

Copyright ©2007 Terry Hancock / Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)

Originally published at www.FreeSoftwareMagazine.com.

You must retain this notice if you reprint this article.

This license includes my original pictures.