“Former Soviet Union” is a term that often makes people think of a somehow original concept of freedom and democracy. You can observe some heritage looking, for instance, at the facts of today’s Belarus [1,2] and Turkmenistan [3,4].

Anyway, even there, people always have had the will to express their ideas and opinions. Think, for instance, of the samizdat [5], or of the dissidents.

How could native geeks and computer scientists/engineers miss the opportunity to contribute to the free software movement as another expression of freedom and democracy? In this article, hopefully the first of a short series, I will try to outline the rise and growth of free software in the former USSR by interviewing some of the key individuals:

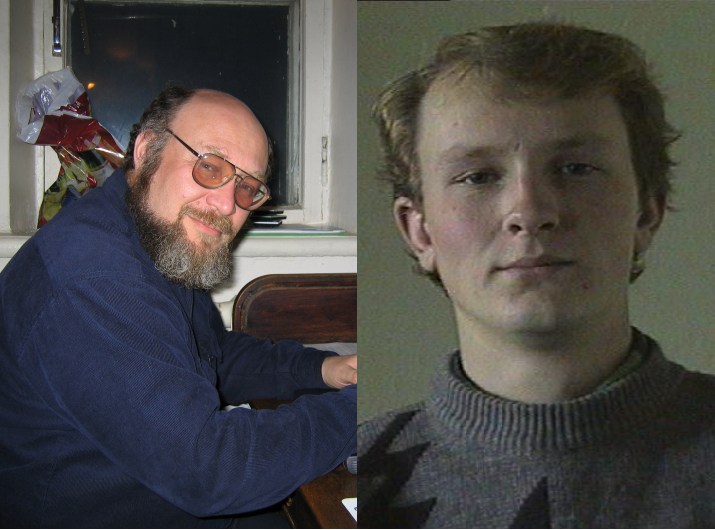

- Alexander Barkov, currently senior programmer at Lavtech (Izhevsk, Udmurtia, Russian Federation) —referred to as Sasha Barkov;

- Aleksey Smirnov, founder and director of the Institute for Logic, as well as founder of the firm ALT Linux (Moscow, Russian Federation) —referred to as Aliosha;

- Oleg Philon, currently senior programmer at IBA Gomel branch, one of the founders of the GomeLUG (Gomel, Belarus) —referred to as Oleg, since his name has no short form;

- Alexander Zhukov, currently a developer at Priocom Corp. (Kiev, Ukraine) —referred to as Sasha Zhukov;

- Yuri Umanets, currently software engineer at Priocom Corp. (Kiev, Ukraine) —referred to as Yura;

- Mikhail Shigorin, currently project manager at

emt.com.uaand member of Ukrainian Linux and Free Software Users Group (Kiev, Ukraine) —referred to as Misha.

Points of note

This article/interview is based on answers collected from April through June, 2005: some information may have changed in the meanwhile. The outline I tried to draw is unfortunately not quite complete; one of the people I had hoped to interview from Belarus (to remain nameless) initially agreed to answer my questions, but then decided against it at a later stage.

It can be assumed that the personal answers from the interviews are representative of a large part of the community, but of course and understandably, they can’t possibly represent the whole story: either due to the countries being different from one another, or due to the differing opinions, background and interests of each individual.

How did free software start spreading in the former USSR?

Sasha Barkov, you are well known for your search engine mnoGoSearch, formerly known as UDMsearch…

Yes, in fact UDM are the first three letters of “Udmurtia”, which is a small republic in the Russian Federation. Its capital is Izhevsk, where I studied, and now live and work. You can get more information about Udmurtia from www.udmurtia.ru/udmitem.

The free software approach gives a starting project many advantages

Are you the originator of the product? And why did you decide to release it as free software?

Yes, I originally came up with the concept for the project. It was intially a very small project. Later, I joined the company Lavtech, and they “adopted” my project.

I chose to release it as free software because the free software approach gives a starting project many advantages. For example:

- it is easier to find new users and thus become famous;

- it is easier to debug a free software program, because your users find and report bugs. Some users fix the bugs themselves and send patches;

- unlike commercial software, free software projects release announcements appear on software news sites without your interaction. News site webmasters watch your site waiting for your announcements to post on their sites. Also, free software is registered in various software catalogs by volunteers. Whereas, in the case of commercial software, you need to post announcements yourself, nobody will do it for you;

- one can start from a very small free software project, and can improve and develop it gradually. With commercial software, one usually has to have a much more complete product to go to market with.

Oleg, you were a Debian GNU/Linux developer: when and how did you first come into contact with free software?

Well, I have been lucky enough to work with computers throughtout the majority of my life. I’ve spent the last 18 years working on microcomputers—I started as soon as the first IBM-compatible machines appeared in our city. My first acquaintance with free software, namely with an ancient Linux Slackware distribution on 5¼" floppies, happened in 1996. I used the only UUCP-based email server available in our town at the time, and got some files via ftp-mail service. Then I decided to practice with ftp commands locally, and so began this highly addictive endeavour. Since then I haven’t stopped. And, with the growth and maturity of free software applications, the proprietary software usage on my work and home computers shrank to very few programs. Now, when I’m forced to use some Windows applications, I hide them under VMware’s virtual machine.

The turning point of my dealings with free software was in 1998. With some other Linux enthusiasts, we started setting up the first real internet server in a state telecom company. Initially it was only an amateur project, and we worked as volunteers. The work really started to progress when TCP services became available in our region. For example, formerly we only had UUCP mail, and we got a computer to migrate that mail service from SCO Unix, without any support, to Linux, with which we had some experience.

My first attempts to contribute to free software was related to my job: I had to compile 64bit code on Sun Solaris

Sasha Zhukov, can you tell us when you started working on free software and why?

It depends on how you define “working on free software”. If you mean using it, it was long ago, when I was a freshman at university. My first attempts to contribute to free software was related to my job: I had to compile 64bit code on Sun Solaris machines. At that time gcc for Sparc was not very well suited to 64bit compilation, so I did a lot of testing and posted some notes on mailing lists.

My first free software project was javamaildir, a small library used to access (read/write) mailboxes on servers. The project is hosted on SourceForge and it’s used in large-scale email systems. I currently develop one such system: the Ukrtelecom’s (the national Ukrainian telecom company) email system.

How do people contribute to the diffusion of free software?

Yura, you’re known for your contribution to ReiserFS and now to ClusterFS. How did you start your “adventure” in the free software world?

I started working on free software more than 6 years ago. The main reason for this was to get into the realm of real knowledge of operating systems, graphical desktop environments, system utilities, and so on. That’s really impossible with Windows, as there’s no source code available to learn anything from it.

How do people contribute to the diffusion of free software?

Since I develop enterprise email systems, I started searching for Java projects exim/sendmail MTAs and pop/imap toasters. In the process I came across James, and when I looked into it and found that it wasn’t exactly enterprise capable, so I started contributing patches to the James guys. I should point out that it’s hard work: it seemed to me that the James staff hadn’t been exposed to real enterprise email systems, that is to say systems capable of handling hundreds of thousands of users.

Oleg, how do Linux Users Groups in Belarus produce free documentation? And how do they contribute to the diffusion of free software? Are there meetings, or something else?

Well, the project I told you about had an additional result for me and the other Gomel “linuxoids”. We tested ourselves in a real project, which eventually yielded some money, and we formed our Gomel Linux Users Group. The other consequence was rooting Debian GNU/Linux in our city. Since then, every server I have setup, and the distribution I always recommend, has been Debian based, just as do other seasoned Linux users.

I’m sure you know the feeling: when you get so much from the free software community, you feel the urge to give something back. I took every opportunity to propagate Linux usage amongst my friends and students, and I wrote technical articles. For a short period of time I also maintained a simple packet in the Debian project.

We’ve had regular meetings and have offered support for newcomers. Even with serious server problems, most of the time you know how to find help from more experienced Unix admins. At one time, when internet access was a problem, we cooperated in order to download and burn CDs with the latest and greatest distros. Three years ago we had good relations with the IATP project. They ran computer classes with internet access in the Gomel state library, and each week gave us the opportunity to gather for a couple of hours, and to experience the seminars and lectures.

We build ALT Linux distributions from scratch

Aliosha, you officially distribute your version of GNU/Linux. Is it based on an existing distribution, or did you build it from scratch? Does it use instruments you’ve developed to improve the installation process, the functionality, or usability for the end user? And how do these instruments come back to the community?

We build ALT Linux distributions from scratch. They are all based on our repository named Sisyphus. The ALT Linux site has more information on Sisyphus and our distributions.

We have made several essential improvements in the package building technology, there’s also an example of this on our site.

There’s complete apt/rpm support in all ALT Linux distributions. We’ve made a lot of security enhancements. All of the software we develop is free software, and we do our best to bring it to the mainstream. There’s a list of some of the free software projects we take part in on our site as well.

Till now we’ve been using installation and configuration software based on Mandrake. But soon ALT Linux 3.0 is to be released, and for that we are using a new installer and new configuration software which we have designed ourselves.

How is free software implemented in schools, organizations and public institutions?

Aliosha, how do Russian schools, organizations and government institutions rely on free software? Do you know the approximate percentage of users of free software in Russia?

I don’t know the exact percentage, but we sell about 60000 ALT Linux distributions a year. A real success story for 2004 was selling 12000 computers with pre-installed ALT Linux for use in schools in the South Federal District. We have also won a tender of the Federal ministry of economic development: they have asked us to prepare recommendations on the use of free software in government departments. We’re now also involved in the federal “Electronic Russia” project, and through that I hope we’ll achieve a lot more for free software in Russia.

Free software and world interchange

Aliosha, what about the diffusion of your distribution in the rest of the world?

Our distributions are also used in the Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus. We’re planning to sell them in other countries, but we don’t have much experience doing so and are looking for partners.

Sasha Zhukov, you told us you produced a Java-based email system and I believe you offer support for it. In which countries is your system most widely used?

I guess it is the Ukraine, but there are a lot of people who use it in Russia. International users from Europe and the US are only about 5% of the total number of users.

How did the previous and current governments help the international commercial interchange? Have you experienced any differences?

The government doesn’t care. But sometimes the police ask us to help with their investigations of fraud and other offenses that are connected somehow with the system.

Free software for unskilled end users

Sasha Barkov, mnoGoSearch runs under Linux and Windows. Are there other operating systems under which it runs, or that you have plans to port to? And how do you feel your free software is useful and “instructive” to the users of proprietary operating systems?

Our software is commercial for the Windows family of operating systems, and free for all Unix variations, both free and proprietary. It runs on most modern Unix systems, including GNU/Linux, FreeBSD, MacOSX, Solaris, HP UX, etc. If someone complains that it doesn’t compile/work on a platform, we’ll usually try to fix it straight away.

I’m happy when any of our users contribute to the project. There are many ways thay can do it: from linking to our site, reporting a bug or contributing a piece of code, to purchasing our commercial support or our commercial releases for Windows. The operating system itself doesn’t really matter.

Spam and free software antispam

Misha, you’re the maintainer of the site Linux.Kiev, so I believe you are a privileged observer of the spam problem.

Uh-oh. Yes, but it’s more due to me being the postmaster for linux.kiev.ua and several more domains hosted there.

How do you fight spam?

I personally use SpamOracle and a few custom procmail filters as a user on that system; there are some pretty small Postfix anti-UCE setup there too (no RBLs or DNSBLs though—the one that was found suitable failed to respond for a few hours on a couple occasions and that, with accompanying rejects, was enough to cause me to get rid of it altogether).

It’s letting up to a dozen spam emails through to my inbox daily with anywhere between 120 and over 200 getting junked (including bounces), and between 3 and 10 solicited personal emails (mostly from people using Outlook or the Bat!) being false positives. Scary but not serious enough to change.

We plan to deploy SpamAssassin or DSPAM 6 as the new hosting server added to the pool should handle that. The older one is already way too busy, it’s just a Duron 800/512M.

Do you know if there are techniques and technologies being used to fight spam developed in the Ukraine, either in the universities or in the IT companies? If so, who developed them?

Major ISPs and mail hosts are in this business, I would single out Vladimir Sharun, reachable on vladimir DOT sharun AT ukr DOT net (I published his email address under his permission —GP) who develops perhaps the most usable blocking list software, techniques and processes around.

Conclusion

This is one of the free software puzzle’s pieces. As you see, nothing restricts geeks and scientists from doing, often for free, what they like or feel.

In the next parts, we’ll try to complete the puzzle and, hopefully, we’ll discover that this puzzle is not too much different from other, corresponding puzzles all over the world.

Bibliography

[1] Tom Stoppard. Accidental tyranny. The Guardian, Oct. 1st, 2005.

2(http://www.rferl.org/featuresarchive/country/belarus.html), 2005.

[3] Peter Böhm. Der graueste Flecken auf Erden. Die Weltwoche, (32), 2005.

4(http://www.rferl.org/featuresarchive/country/turkmenistan.html), 2005.

[5] Daniel James. The content tail wags the IT dog. Free Software Magazine, (1), February 2005.

[6] John Locke. Mail servers: resolving the identity crisis. Free Software Magazine, (2), March 2005.