It has been said that "'best' is the enemy of 'good enough'". The Network File System (NFS) may be a good example. It's often overlooked in favor of more capable (but more complex!) resource sharing software like Samba, which can network easily with Windows computers. But if you have a home LAN with a lot of GNU/Linux machines on it, you don't need Samba. NFS will do just fine, and it's very simple to set up. I've been using this configuration for about 10 years now (essentially since I started using GNU/Linux in the first place).

I've been using the Network File System (NFS) a lot longer than I've been using GNU/Linux, although I didn't necessarily know it at the time. It's a very simple system to use -- part of the everyday plumbing of a GNU/Linux system. In fact, until fairly recently, I imagined that practically everyone who used Linux used NFS. But then, many people don't have multiple computer systems to work with and some of them that do use other systems like Samba, which have additional advantages like inter-operation with Microsoft Windows. But if you have an all-Linux (or Unix) network, it's hard to beat the sheer simplicity of NFS.

In fact, until fairly recently, I imagined that practically everyone who used Linux used NFS

The Network File System (NFS)

NFS is a very old standard for sharing file-systems, released in 1984 by Sun Microsystems -- about the same time as the GNU project was starting. Nevertheless, it is still a very practical solution for sharing filesystem on a local area network (LAN), provided all of the computers on the net are Unix or Linux based (I'm not sure if it can be used with other operating systems, but if you need support for Windows, you'll most likely want to use Samba instead).

NFS is a very old standard for sharing file-systems, released in 1984 by Sun Microsystems

Of course, NFS has evolved since then, with newer versions of the protocol being released over time:

| Version | Date Released |

|---|---|

| NFS | 1984 |

| NFSv2 | 1989 |

| NFSv3 | 1995 |

| NFSv4 | 2000 |

| NFSv4.1 | 2003 |

Given this timescale, though, it's pretty safe to assume that any reasonably new system you are installing will have support for the latest NFS, so I won't bother with special settings for versions, except to note that it is possible to configure a newer client to access a server using one of the earlier protocols (I have had reason to do this due to some legacy systems that I had to hold back on a much earlier version of Debian, but it's not a common need).

The architecture is a simple client-server system. The server machine makes a local directory (usually a partition, but this isn't required) available to clients over the network. On the clients, the directory is mounted with the filetype specified as "nfs", and queries to the filesystem actually go over the network to retrieve data from the server.

The server machine makes a local directory (usually a partition, but this isn't required) available to clients over the network

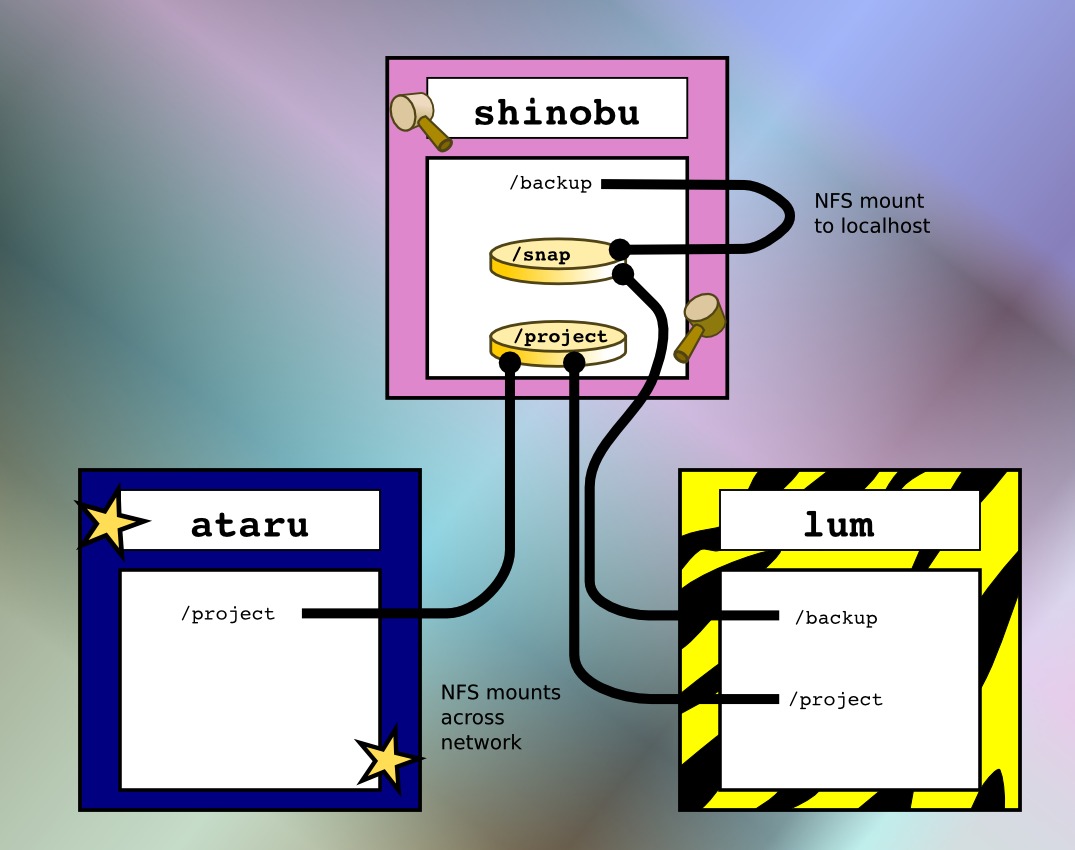

"Client" and "server" are really just programs running on the computers in question, and are relative to each shared drive. It's perfectly possible to have multiple servers or for a single machine to be both client and server. In fact, it's even possible to use an NFS mount on the same machine.

Installing in Debian

In Debian-based distributions, there are two main NFS packages: nfs-common provides the basic needs for a client (plus some needed by the server) and nfs-kernel-server provides additional support needed only on the server machine.

Installing on the server requires both packages to be installed:

$ su

# apt-get install nfs-common nfs-kernel-server

while a machine which will only be used as a client will work with only the nfs-common package if you want:

$ su

# apt-get install nfs-common

You might want to just install both as a matter of course, though, as they are not large packages (the main reason for not installing the kernel server is if you are concerned about security issues, but this is usually not a serious problem on a home LAN operating behind a firewall).

Configuring the server

The configuration you will need to edit on the server is controlled by a single file: /etc/exports. It is in this file that you tell the server what directory you want to share, which computers you want to be able to mount it, and on what terms. So, for example, on the fileserver on my LAN, I have something like this:

/etc/exports (on server, called "shinobu")

# /etc/exports: the access control list for filesystems which may be exported

# to NFS clients. See exports(5).

/snap lum(ro,sync,no_subtree_check) localhost(ro,sync,no_subtree_check)

/project lum(rw,sync,no_subtree_check,no_root_squash) ataru(rw,sync,no_subtree_check,no_root_squash)

This allows the /snap drive to be mounted read-only on the client "lum" and also on the localhost. I use this arrangement to mount my snapshot /backup partition for recovering data from accidentally-deleted files (the backup system itself works on /snap directly, which it needs to be writeable). Mounting the /backup drive read-only even on localhost avoids accidentally corrupting the backup system.

By default, NFS handles the root user a bit oddly -- when you access an NFS partition as root, you suddenly become the user "nobody" on the server machine

In addition, a second drive, /project is mountable by two other machines, "lum" and "ataru". In both cases, the drive is mounted read/write so it can be used like a local drive.

By default, NFS handles the root user a bit oddly -- when you access an NFS partition as root, you suddenly become the user "nobody" on the server machine. This greatly restricts your access (more than a regular user, not less). The root user's privileges get "squashed".

The reasoning here is that, while you may have root privilege on the client machine, you might not have it on the server! However, if you are in a sufficiently controlled environment with trusted people, you can avoid this by using the "no_root_squash" option as I have done for /project above.

Configuring the client

Configuring the client is done in the "/etc/fstab" file, just as with other filesystem options. On the machine "lum" from my example, I will need these lines:

Client configuration on "lum"

shinobu:/snap nfs /backup defaults,ro 0 0

shinobu:/project nfs /project defaults,rw,users 0 0

On "ataru" I'll need jut this line (ataru isn't allowed to mount the /snap partition in this example):

Client configuration on "ataru"

shinobu:/project nfs /project defaults,rw,users 0 0

Finally, on "shinobu", I'll also need a line for the local NFS-remounting of the /snap partition:

Client configuration on "shinobu"

localhost:/snap nfs /backup defaults,ro 0 0

User names and user IDs

There is one piece of awkwardness to look out for: NFS uses user ID numbers to identify file-owners, not user names. This means that you will get some weird behavior if your different machines don't agree on which users have which numbers.

On my tiny, hardly-ever-changing LAN, I decided it would be simpler to just manually synchronize my user configurations

There are ways around this. One is to synchronize user IDs across your network with something like NIS (which used to be called "yellow pages" before the trademark issue was brought up). And, most likely, other methods have been invented.

However, on my tiny, hardly-ever-changing LAN, I decided it would be simpler to just manually synchronize my user configurations by editing the /etc/passwd files on each machine (or by creating users in the same order every time).

Good enough

There are more robust file systems, file systems for demanding multimedia environments, file systems with greater support for multiple operating systems, and file systems with greater tolerance for errors. However, for most purposes I've ever needed on a home LAN, NFS is simply good enough, and very, very simple to set up. I highly recommend it if you don't want the hassle associated with other approaches.

Licensing Notice

This work may be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, version 3.0, with attribution to "Terry Hancock, first published in Free Software Magazine". Illustrations and modifications to illustrations are under the same license and attribution, except as noted in their captions (all images in this article are CC By-SA 3.0 compatible).