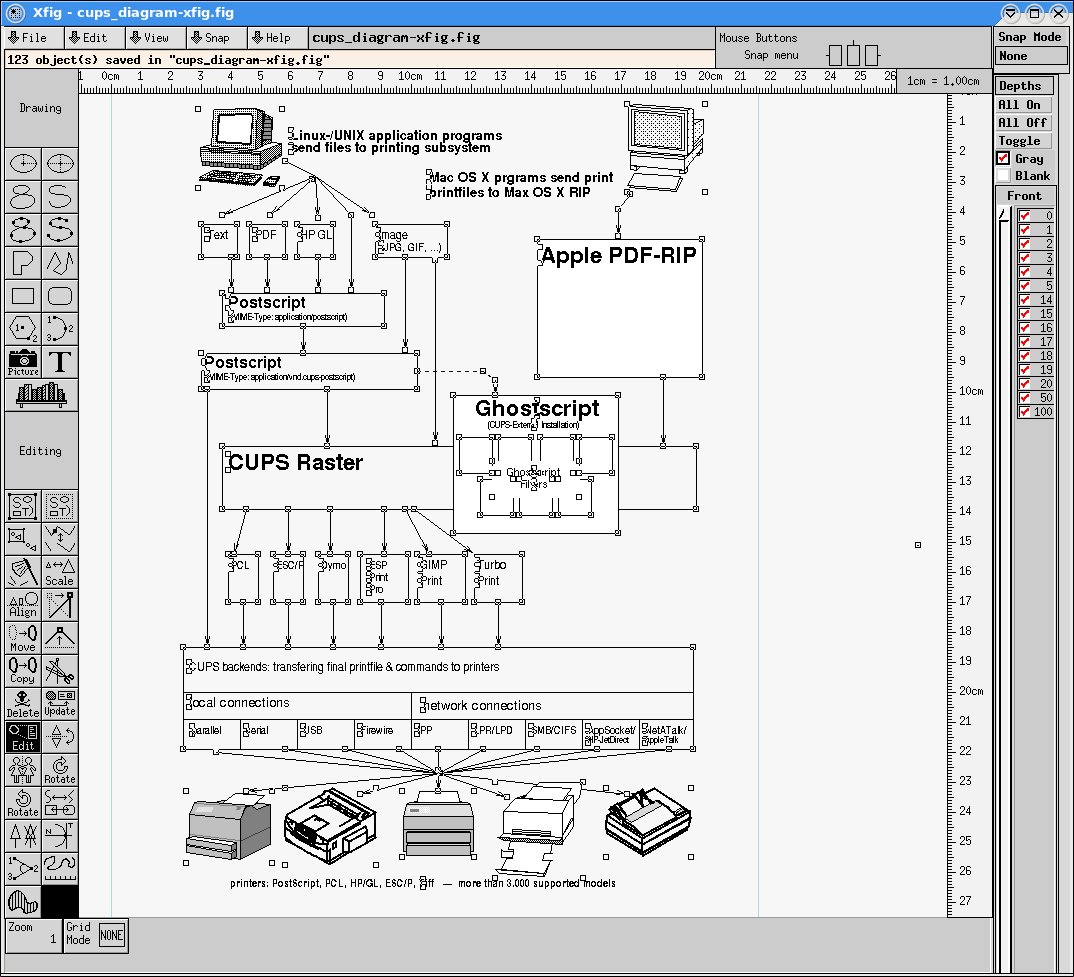

Just as there are "classic" cars that never seem to go out of style, there are some classic pieces of software that remain useful long after most of their contemporaries. One of those programs is Xfig, a vector graphics editor hailing from the days of academic Unix workstations. Like the more famous TeX, Xfig hasn't seen significant updates in several years—and for the same reason: it's just about perfect like it is. It is showing its age in the style of its graphical interface, and it does have some fundamental limitations compared to more modern graphics tools, but for the simple technical diagrams it was intended for, it is still hard to beat.

Xfig is an older package, developed for Unix workstation environments such as SPARC. If you were using such a system to prepare research papers in the 1990s, it's very likely you would have encountered it. The output from Xfig was very easy to incorporate into TeX or LaTeX papers, and this made it a favorite program among academics.

Xfig is an older package, developed for Unix workstation environments

Of course, it was not very competitive against proprietary software then available, such as Corel Draw, but those programs were generally not available for Unix, and neither were they really designed for the technical drawing needs of academic publishing. So, it's not surprising that Xfig is weak on such finer artistic tools such as Bezier curve editing. Instead, Xfig has simpler "interpolated" and "approximated" "spline curve" tools and a separate "polyline" tool (a spline is slightly simpler than a Bezier curve and therefore not quite as flexible to edit). This approach may not be as intuitive for editing general curve objects (the workhorse tool for creative graphics in programs like Inkscape), but it works very well for simple line-art illustrations.

Even though Xfig is a true vector graphics editor, it is ergonomically designed around the needs of technical diagram editing

More importantly, even though Xfig is a true vector graphics editor, it is ergonomically designed around the needs of technical diagram editing. Grid-snapping is on by default; there is a simple tool for adding arrowheads to lines (although you can also do it through the generic object "edit" dialog); general rotation is not supported, but right-angle rotations are easy; and so on. In some ways it comes closer to a simplified CAD program than to a general vector graphics editor.

Although Xfig was neither my favorite vector graphics editor, nor my first choice for making the diagram in this project, it was unquestionably the easiest and fastest way to produce a publication-quality result. Xfig offers just the right balance between flexibility and simplicity.

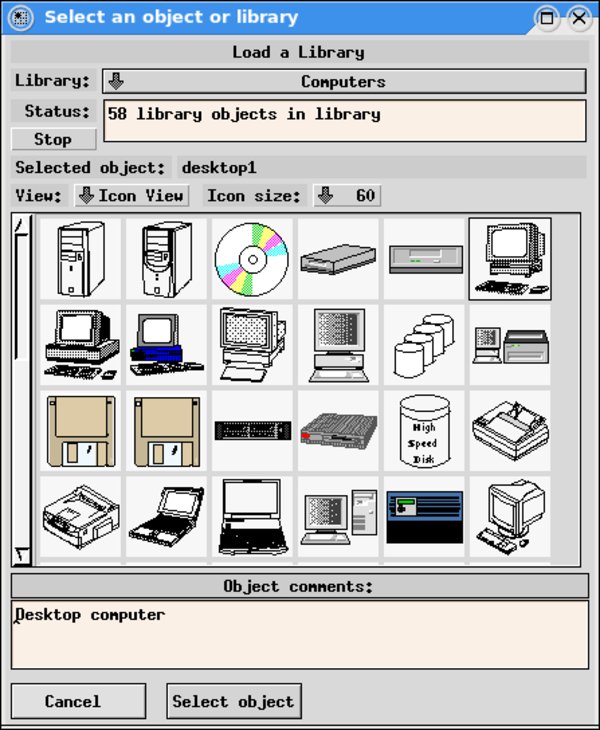

Symbol libraries

Like Dia, Xfig makes significant use of symbol libraries. Unlike Dia, though, its libraries are very well maintained and complete. Unlike most modern vector graphics programs like Inkscape, for which there is no real symbol library, forcing one to use Open Clipart instead, Xfig's symbols are extremely well organized, labeled, and integrated into the program. Using symbols in Xfig was easy and intuitive.

Xfig's symbols are extremely well organized, labeled, and integrated into the program

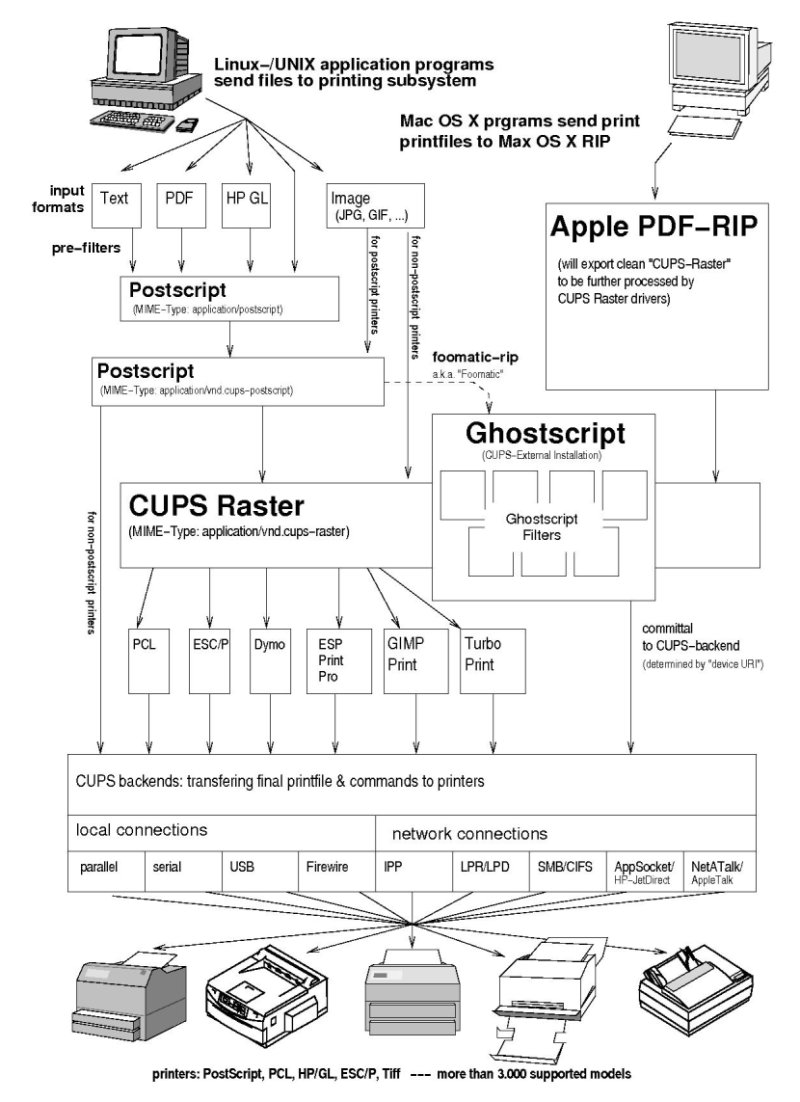

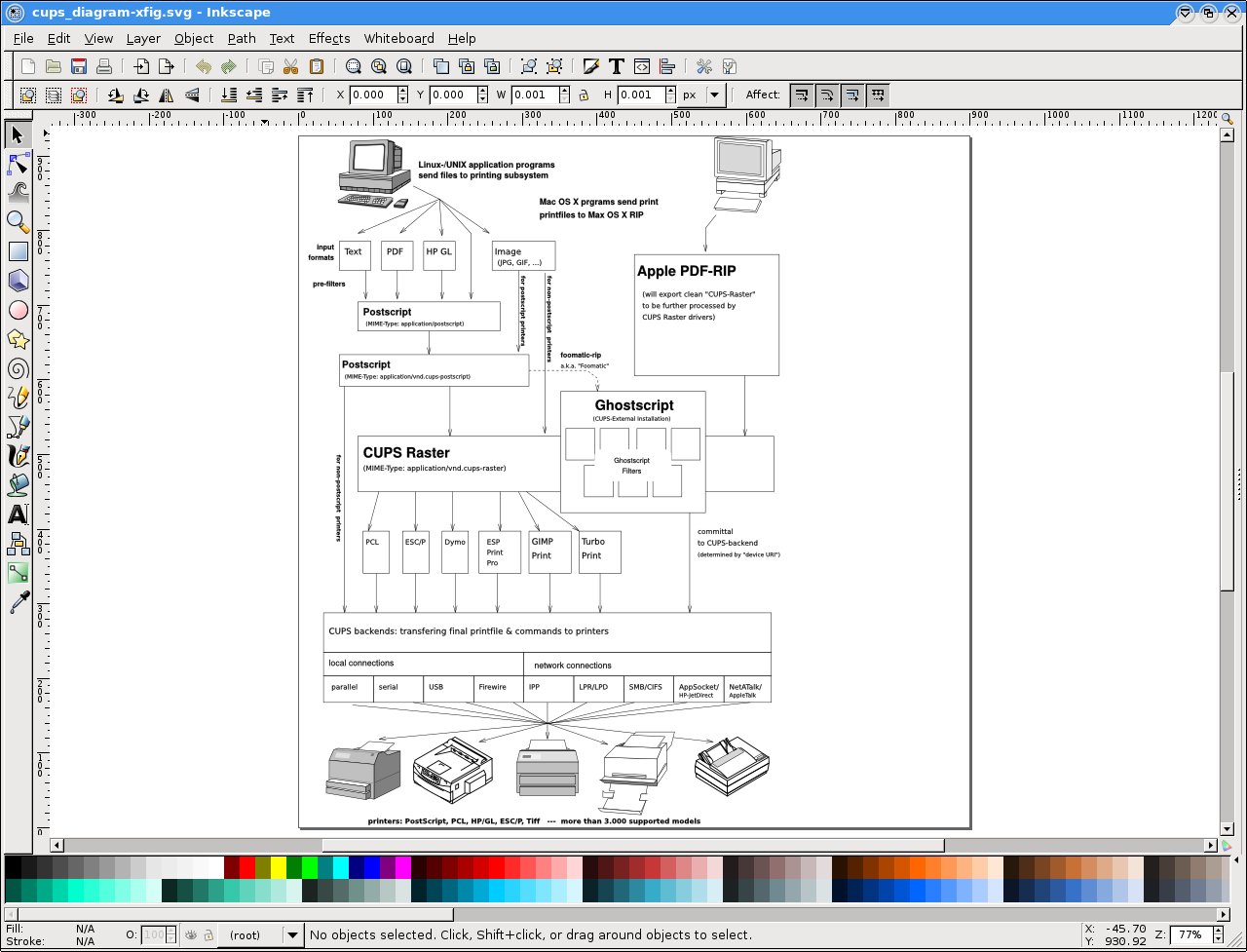

For the CUPS filter diagram used as a drawing example here, I used symbols for the target printers (several different ones to emphasize the point that CUPS supports different kinds) and also for computers representing the sending applications (I tried to pick ones that resembled typical PC Unix/Linux systems and Macintosh respectively).

On the minus side, it does not appear that the Open Clipart art has been included in Xfig's image libraries, nor of course has the very fine artwork in Xfig's library been incorporated into the Open Clipart collection.

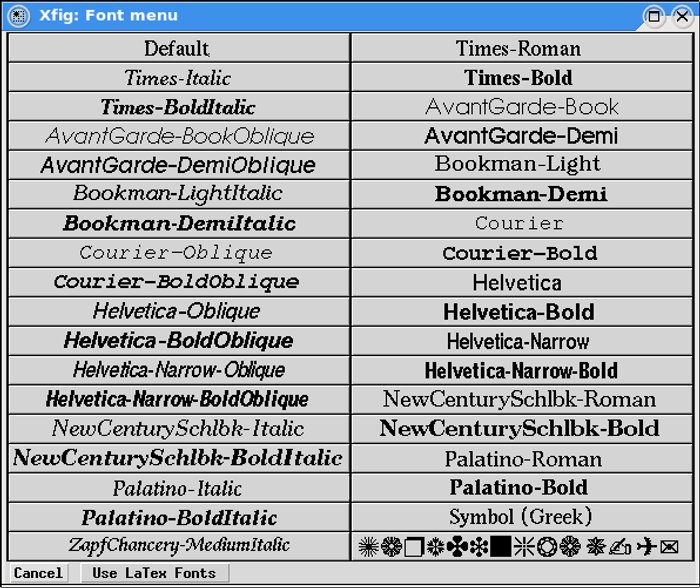

Text

Text support is fairly straightforward, though certainly not the best among the programs I tested. There is no true multi-line text in Xfig. Instead, when you press return while typing text directly into the program, you get a new text object positioned appropriately below the first one.

In order to paste multi-line text into Xfig, I had to go through a somewhat non-intuitive process. I typed "a" into the interface, then switched to the edit tool to set the size and font. Then I re-selected the text, and created new lines "b" and "c" (for a three-line text block). Then I returned to the "edit" tool to get a dialog window which would allow me to paste in each line of text that I needed. Though this might sound very awkward, it was fairly fast to do in practice. But it obviously falls far short of having real multi-line text.

Fortunately, in this kind of diagram, there aren't that many multi-line text blocks to worry about.

Xfig maintains its own fonts, and does not, therefore give you the full range of fonts that are installed on your system. On the other hand, the font picker is extremely easy and quick to use, and the major fonts you are likely to need are provided.

Boxes

Laying out the boxes representing each of the data states in the CUPS process was really easy in Xfig, partly due to the grid snapping behavior, which was on by default. This made for a very fast start on the diagram.

Connectors

For the process flow in the diagram, I used simple polyline objects. After they were laid down, the "toggle arrowhead" tool made marking the flow direction extremely fast and easy.

File formats

Xfig was originally designed to work well with TeX and Postscript, the most common tool chain available in the early 1990s. However, SVG export capability does exist, though the menu claims it is only "beta" quality. My test with the CUPS diagram shows a near-perfect rendering to SVG, as rendered here by Inkscape.

Final remarks

I didn't expect that much from an "obsolete" program like Xfig, which I hadn't used in years, but it surprised me. With its simple (though admittedly no longer very standard) interface and convenient tools, it made the job of drawing this diagram extremely fast and easy. I finished this drawing much faster than I expected to, and faster than I would've been able to do it in Inkscape.

I didn't expect that much from an "obsolete" program like Xfig, which I hadn't used in years, but it surprised me

Nevertheless, despite the short time, the results are very good looking: much better than what I managed with Dia in the same time. With excellent SVG export capability, it also occurs to me that Xfig would make a good way to quickly start a drawing which could later be modified with the more sophisticated tools of one of the modern graphics editors such as Inkscape.

Xfig is not for every drawing project, but for diagrams like this one, it is an excellent tool: it makes it easy to produce very high quality output in very little time.